The Howard Greenberg Gallery in New York presents an exhibition of the famous American photographer focusing predominantly on his most prolific decade : the 1940s.

Weegee’s photographic advice was reportedly something to the effect of “F/8 and be there”. This statement is a perfect, but probably apocryphal summary of one of the most important photographers of the first half of the 20th century.

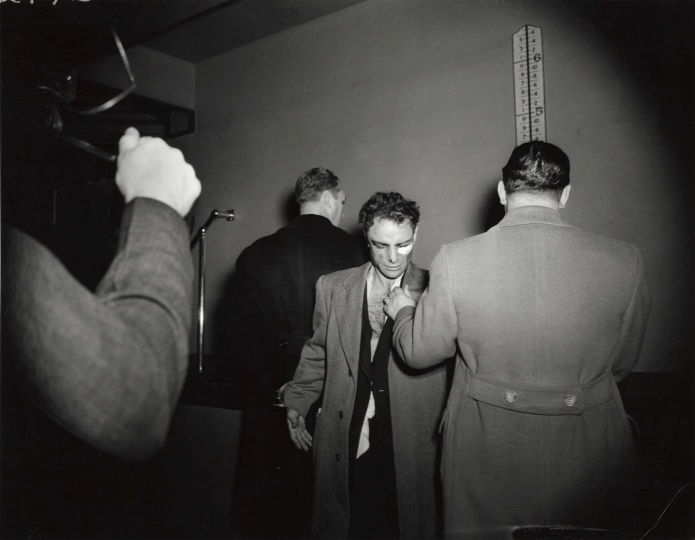

Born Usher Fellig, later Americanized to Arthur Fellig, Weegee took the “be there” portion of his advice to heart. He earned the name Weegee as an alternate spelling of Ouija, because of his preternatural ability to get to the scene, and because it does not really make sense that “Ouija” should spell Weegee. He must have some kind of supernatural power, always the first on the scene, getting shots no one else would ever manage to get then selling them to the papers mere hours after the fact. In reality he was sleeping in his car listening to the police scanner and developing pictures in a makeshift darkroom in the back of his car. Although, ask Weegee how he ended up on the right bloc at the right time and he would mention a vague sense that something was going to happen, but then again, there were few times Weegee wasn’t working. Stay up all night and always have your camera ready is a great way to get the shot. The fact that for his early work Weegee was lugging around a huge 4×10 Speed Graphic Press Camera makes his rapid unplanned shots that much more impressive.

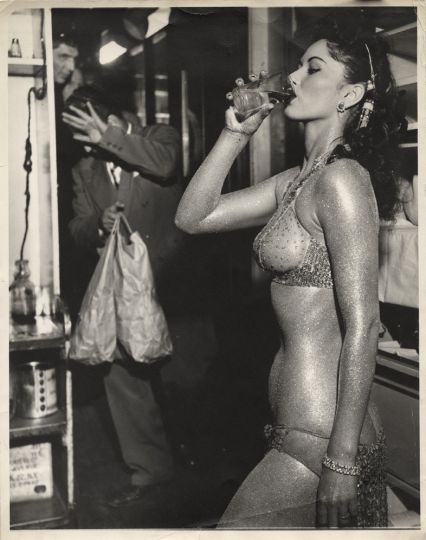

It was not all just being in the right place at the right time, Weegee was an early proponent of marketing himself, stamping his photos with his “PHOTO CREDIT THE FAMOUS WEEGEE” rubber stamp and selling them to his newspaper contacts who knew, if they needed a shot, Weegee would deliver. He was not an artist sitting in an ivory tower deconstructing theory, he did not produce work for a gallery, or to be shown anywhere other than in the pages of a daily newspaper that would be irrelevant in a few hours. He was a working man, he did his job and he was good at it. There were others like him, others who wanted to be as prolific, as talented, but he carved out his niche as the best of his kind, and when we remember the bygone days of a cigar chomping, shabby suit wearing reporter with a huge flash bulb, we are indebted to Weegee. The reason that archetype exists is because of Weegee, and he was much more than a stereotypical newspaperman. Weegee, if it was possible, spoke to his subjects and made them feel comfortable before getting the shot, but other times he would have to act on the spur of the moment, relying on his timing and eye. He was quoted as saying that “dead bodies are the easiest to shoot because the stiff isn’t going anywhere.”

Weegee remains relevant and indeed is being written about in this publication because he straddled two worlds. His pictures graced the front page of the New York Post, but they were also included in one of MOMA’s first photography shows, placing him squarely in photographic history. His eye and his frames, his subjects, and his sense of space and proportion all foreshadowed everyone from Arbus to Winogrand. His photographs, now ‘works’, were collected in books and exhibited nationwide. Photography was gaining acceptance as an art form and Weegee was at the forefront. Later in his career Weegee worked on what he called “creative photography” – distorting the image using plastic or long exposure times. He took portraits of Salvador Dali and Andy Warhol as well as female nudes and burning buildings. There is no better way to understand the development of photography as an art form that to trace Weegee’s career.

The International Center of Photography is home to the world’s largest holding of the work of Weegee (1899-1968). Bequeathed to ICP in 1993, the Weegee Archive contains 20,000 original prints and negatives, films, tear sheets, manuscript drafts, correspondence, and other personal memorabilia of one of the most inventive figures in American photography. Best known for his tabloid news photographs of urban crowds, crime scenes, and New York City nightlife of the 1930s and 1940s, Weegee later dedicated himself to what he called “creative photography”—images made through distorting lenses and other optical effects.

John Hutt

John Hutt is a writer specialized in arts based in New York, USA.

Weegee

February 16 to April 1, 2017

Howard Greenberg Gallery

41 E 57th St #14fl

New York, NY 10022

USA

http://www.howardgreenberg.com/

Visitors can visit the collections —housed at the ICP space at Mana Contemporary in Jersey City— by appointment. For more information: https://www.icp.org/facilities/icp-at-mana.