Exposed: Voyeurism, Surveillance and the Camera Since 1870

This exhibition examines photography as an invasive act. It focuses on photography that, whether by intention or effect, challenges our common ideas of privacy and propriety. Most of the pictures on view were made without their subjects’ knowledge—some were made using special technologies, such as right-angle viewfinders, telescopic or wide-angle lenses, and infrared flashes and films. Many were taken quickly and discreetly on the street, or simply while peering down from a window, protected from outside observation.

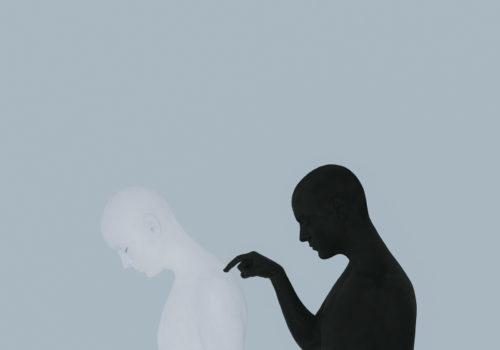

Voyeurism is a potent, widespread, yet generally unacknowledged aspect of photography, practiced by artists, amateurs, professionals, and spies. Exposed asks whether such invasiveness is inherent to the medium itself.

In this exhibition we define the voyeuristic impulse broadly as an eagerness to see a subject commonly considered taboo. We explore voyeurism’s relationship to photography in five areas: the work of the unseen, clandestine photographer; voyeurism and sexual desire; celebrity, with its confusion of private and public life; the witnessing of violence and suffering; and surveillance in its many forms.

Exposed traces these distinctive kinds of looking from photography’s early years to the present. With the mass manufacture of the hand-held camera in the late 1880s, virtually anyone could take a snapshot, making privacy an increasing concern, subject to both ethical and legal scrutiny. The issue has grown even more pressing in recent years as camera phones, webcams, and surveillance devices have become a staple presence in the public realm. Artists since the 1960s have addressed the subject, and the new range of surveillance technologies, in works of experimental film, video, and online art. Many of the contemporary artists in the show probe the idea that technologies that once seemed intrusive and violating can now be sources of comfort, protection, even entertainment, and that as a society we appear to no longer regard voyeurism with the caution we once did.

By examining the ever-present eye of the surveillance camera of today and the nineteenth-century street photographer spying on his subject with a concealed camera, the exhibition explores how our definitions of respect, vulnerability, and security have shifted over time, altering our understanding of what it means to look and be looked at.

Sandra S. Phillips, Senior Curator of Photography In collaboration with Rudolf Frieling, Curator of Media Arts

Five Themes of Forbidden Looking

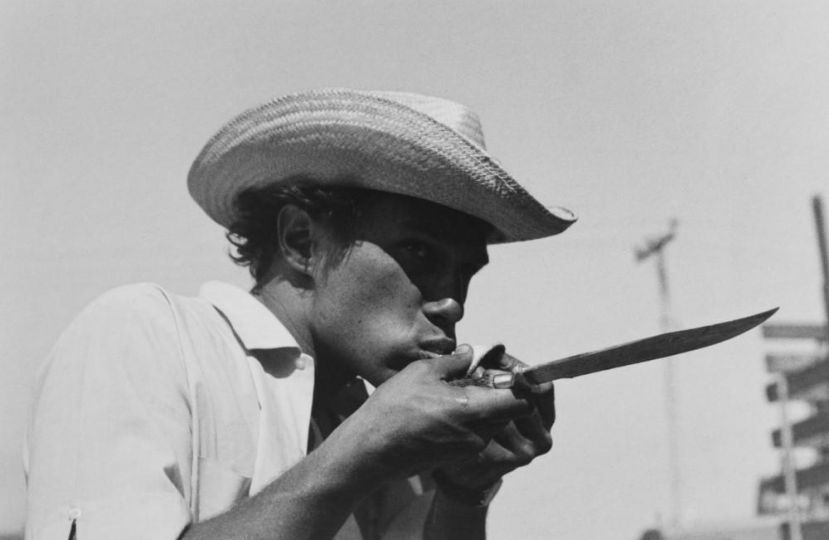

The Unseen Photographer In the 1870s, facilitated by advances in technology, the camera moved out of the studio and into the street. With a small device in hand, photographers found it relatively easy to catch someone by surprise or completely unawares; by the 1880s cameras would be disguised as tie pins, hidden in canes, or found peeking out of the heel of a man’s shoe. Such equipment was used mostly by nonprofessional photography enthusiasts, who quickly became a nuisance as they preyed on their unsuspecting targets. The idea of stalking is retained in the way we talk about pictures: we “take” them, or we “shoot” them.

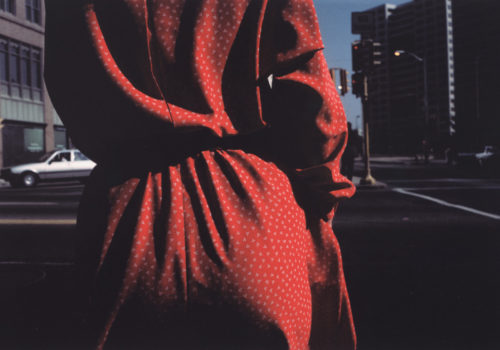

Many early street photographers were accomplished amateurs: Paul Martin and Horace Engle used concealed cameras to photograph everyday scenes such as people asleep on the beach or reading on the tram. The social reformer Jacob Riis employed the new flash technology (a gun that shot flash powder with an alarming noise) to expose the deplorable conditions of urban poverty. In 1916 Paul Strand’s pictures of the poor on New York City’s streets captured naturalness and even intimacy by using a camera disguised by a false lens— the real one pointed sideways. Walker Evans’s pictures demonstrate a continuous fascination with invading the privacy of those he photographed, subjects ranging from people sleeping on city streets to the intimate living spaces of poor farmers in the American South, culminating in his hidden camera portraits of passengers lost in thought on the New York subway. The 1960s saw these precedents revived and transformed in a new kind of documentary photography; the muscular inquisitiveness of Garry Winogrand, for example, embraced not only what was directly in front of his lens but also collateral information on the periphery. This tradition is a living one, still actively pursued by artists such as Anthony Hernandezand Philip-Lorca diCorcia.

Voyeurism and Desire Sexually explicit photographs have been around since the camera was invented. Though subtle, there are differences between straightforward eroticism and pictures made out of a voyeuristic impulse, where the photograph can place the viewer in the position of a peeping Tom. Examples of the latter range from early stereoscopic views that offered a private, three-dimensional pornographic experience to the contemporary work of Merry Alpern, who photographs sexual encounters in a New York brothel through an unnoticed window.

In some decorous nineteenth-century photographs, still dependent on conventions of painting, we see a beautiful nude woman, but also notice the photographer reflected in the mirror behind her. Surrealist artists Man Ray and Pierre Molinier worked in modes associated with pornography to create powerful and strange pictures that examine the act of looking at sex. Alfred Kinsey’s scientific archive of sexual research, compiled in the years following World War II, included anonymous pictures of sexual activity surreptitiously observed. The sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, and the permission it gave to be more explicit about sex, has made voyeuristic looking something of a subset in contemporary art photography. Reexamining the roles assigned to women after the 1960s, Susan Meiselas documents young strippers who are self-aware in potentially exploitative situations. Nan Goldin observes the intimate lives of her friends and lovers in The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. Robert Mapplethorpe sought to make art through pornography, and Stephen Barker and Kohei Yoshiyuki have made pictures of illicit sexual escapades occurring in plain sight. Fashion photography, especially the work of Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin, has used the aura of voyeurism to imply a prurient allure. With the advent of the web, invasive looking can be done by anyone at any time. We can now see anything, virtually, if we take the time to find it.

Celebrity and the Public Gaze Photography invented modern celebrity culture. While portraits of the famous existed in painting, it was only in the 1870s, with the development of the small camera and fast film, that unposed pictures of well-known figures could be made quickly and inexpensively. The perfection of the halftone process allowed such pictures to be reproduced in newspapers, initiating a culture of seemingly limitless pursuit and dissemination. The tension between the photographer and the famous person—who desires both privacy and publicity, and whose persona depends on a kind of notoriety—is often evident in the photograph.

The first deliberate construction of a celebrity persona through photography was that of the extravagant nineteenth-century beauty the Countess of Castiglione, who orchestrated some four hundred self-portraits depicting herself in the role of seductress, actress, even courtesan. These pictures anticipated the blurred distinction between public and private, reality and fantasy, that is the principal territory of celebrity photography today.

Some of the countess’s flair for self-fashioning found its legacy in the media-obsessed life and work of Andy Warhol, who was fascinated by the inherently photographic nature of celebrity culture. Richard Avedon’s 1969 photograph of Warhol, taken after the artist was shot by a demented admirer, shows scars on his chest and stomach as evidence of suffering publicly displayed.

In the years following World War II, paparazzi photographers such as Tazio Secchiaroli and Marcello Geppetti met the growing demand for pictures of film stars. Later, Ron Gallela’s aggressive and intrusive efforts to photograph Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’s every move would cease only when a court intervened on her behalf. The simultaneous absurdity and appeal of such photography is underlined by Alison Jackson, whose mock-paparazzi photographs remind us of our insatiable desire to see the foibles of people whom we know in only the most remote way.

Witnessing Violence

A fascination with images of suffering is integral to photography and its history, as is the moral ambiguity that adheres to such pic-tures. The invasive, almost aggressive looking at violent subjects that photography permits raises numerous questions: Who should look at these pictures? Can we justify intruding upon another’s death? Does photography allow us to responsibly bear witness to a victim’s suffering or does it anesthetize us to its horror?

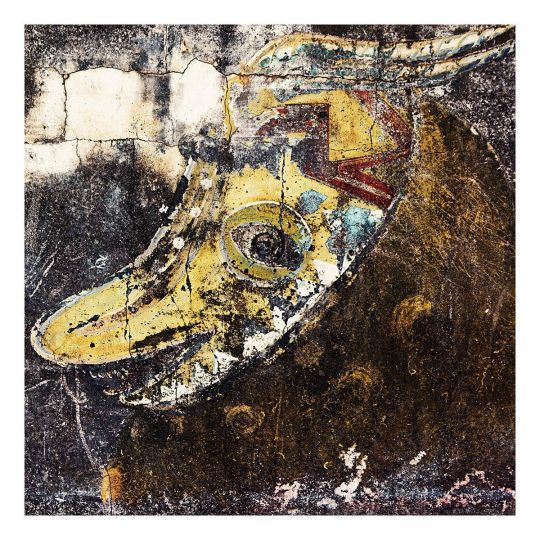

Among the first such graphic photographs were the frankly colonialist pictures Felice Beato made of Chinese casualties during the Second Opium War in 1860. During the American Civil War, photographs of the dead on battlefields, such as those by Alexander Gardner and John Reekie, left people “captivated,” as the New York Times wrote, by their “terrible fascination.” Following the advancing Allied armies into Germany, Lee Miller recorded the flawless beauty and “pretty teeth,” as she wrote, of a young Nazi who took her own life rather than submit to defeat. In the 1960s, a heritage of documenting violence was firmly established when the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, his wife scrambling to assist him, was captured on film and replayed repeatedly on television. At the same time the unfolding violence in Vietnam was broadcast live on the evening news. Susan Meiselas and Gilles Peress pursue this tradition in un-flinching pictures from Central America and Africa.

These explicit pictures have a rich precedent in the photo-graphs published in the populist tabloid newspapers of the 1930s and 1940s. The most vivid were made by Weegee, who documented the violent streets of New York during the war years. His legacy is clear in the pictures of fallen Mafiosi made in Palermo in the 1970s by Letizia Battaglia, and in the work of Mexican tabloid photographer Enrique Metinides.

Surveillance

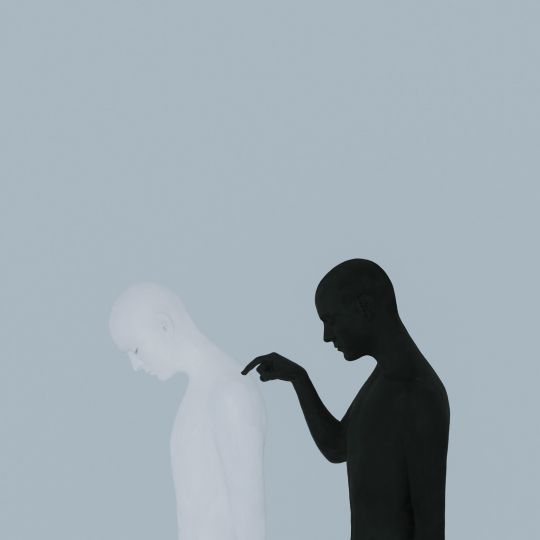

The idea of watching and being watched in public, once the province of street photography, today is more likely to resonate in our minds with surveillance technologies. Surveillance photographs and video footage might appear random, even enigmatic, their composition and style reflecting the automated gaze of the remote devices that produced them; yet they are functional images taken with the intent to observe and control. In fact, photography made for surveillance purposes dates back to the early twentieth century: British police pictures of militant suffragettes, intelligence photos of World War I–era anarchist gatherings in New York, and Cold War espionage activities caught on film by the F.B.I. are some of the historical examples on view. Surveillance serves the witness as well as the spy, for example in the rare and daring pictures taken by prisoners in concentration camps, or of German soldiers on an Amsterdam street, seen clandestinely from a window above. Surveillance pictures invite interpretation, commentary, and reframing, and so have proved to be especially potent sources for conceptual art. Because random tracking of civilians engages a certain anxiety inherent in our culture today, many artists investigate the ideas and methods of surveillance in their work. In this section there are photographs and video works made by artists using high-powered lenses, night-vision equipment, and film developed for spying purposes. Whether making visible the covert operations of government agencies or adapting the visual aesthetics of infrared vision, artists such as Benjamin Lowy, Trevor Paglen, Harun Farocki, and Sophie Ristelhueber have addressed the impact of increasingly sophisticated imaging technologies used for military intelligence, reconnaissance, and engagement. Emily Jacir personalizes her encounter with a webcam in Linz, Austria, while Bruce Nauman records his studio with night vision equipment. Richard Gordon, Simon Norfolk, and Jules Spinatsch turn their cameras back on the watchers. Others, including Vito Acconci and Sophie Calle, document their own acts of tracking strangers. Marie Sester’s robotic spotlight, located downstairs in the Haas Atrium, tracks SFMOMA visitors as they enter, turning the museum itself into a surveillance event.

Sandra S.Phillips

Until april 17, 2011

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

151 Third Street, San Francisco, CA 94103