To Australia’s immediate north lies Papua New Guinea (PNG), its most southern tip less than five kilometres from Australia’s mainland. Yet life for women on this island nation is light years away from their Australian neighbours.

In PNG around 95 per cent of women, known as “meri” in the local dialect, work on farms to provide for their families. Their lives are hard in every sense of the word, and there are few opportunities to break free when one is shackled by tradition, poverty, superstition and lack of education.

If these burdens are not enough, the women of PNG are also beset by domestic violence and sexual assault at rates that are inconceivable; more than two thirds of women suffer horrific abuse at the hands of their men and many are left disfigured after being attacked with knives and axes. Fifty percent of women in PNG have been sexually assaulted, although this figure climbs alarmingly in the more remote provinces, where in some areas 100 percent of women surveyed have been violated. Rape is also endemic, a right of passage for the Raskol gangs that prowl the streets of the capital, Port Moresby.

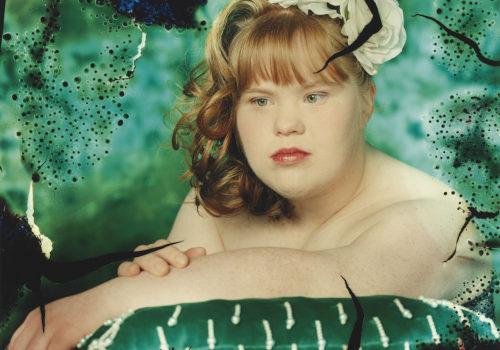

Yet statistics can mean very little when the numbers cited are so loaded with emotion they become incomprehensible; it is all well and good to talk about epidemic proportions, or to claim as the UN does that PNG women face among the highest levels of violence in the world. But what does that figure, that 50, or 90 or 100 per cent look like?

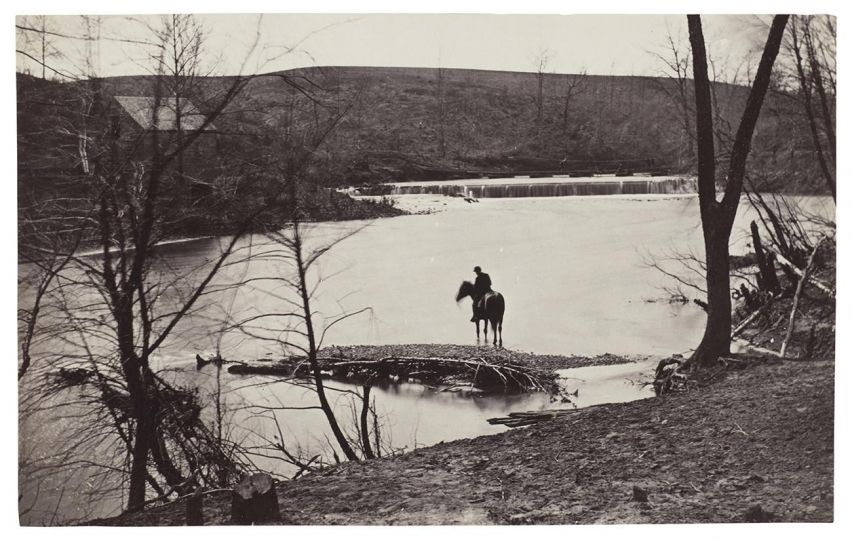

Open the cover of documentary photographer Vlad Sokhin’s new book “Crying Meri: Violence Against Women in Papua New Guinea” and very quickly these statistics become human beings, women whose lives have been shattered along with their bones. Their bodies are indelibly scarred and their eyes silently scream of the terror of numerous beatings and assaults, many at the hands of family members. To look away, is to deny them a voice, one that Sokhin has worked tirelessly to give them.

Sokhin, who is of Russian/Portuguese descent, says he happened upon this story by chance in 2011 when he moved to Australia. “When you freelance you look for stories. I was reading about PNG when I found a survey about violence against women that was about 20 years old. This survey claimed that in some areas almost 99 percent of women were subjected to brutal forms of violence including sorcery-related violence. I found it very shocking. As a photographer I started to look for photo evidence of the violence and I couldn’t find anything other than single pictures that accompanied a few articles. It seemed to me that no one was really interested or had a chance to cover it before, and I thought, well why not me?”

After pitching the story to a few publications, and getting no response, Sokhin decided to take a gamble and go on his own. “In January 2012 I went to Port Moresby. I only had a few contacts, but I arranged permission to shoot at the general hospital and from there people started to introduce me to others, to key figures that were trying to fight violence against women. I also interviewed some Raskols (gang members)”.

He came back from that first trip and showed his work to various people, but he knew he’d only scratched the surface and there was so much more to do. Again the media showed no interest, so Sokhin funded another trip in April of that year. This time he gained greater access through his contacts at the United Nations Human Rights office (OHCHR) in PNG.

Over the next three years every time he went to PNG either on assignment for the OHCHR or on a commission for the then Global Mail, Sokhin would also work on his personal project that became “Crying Meri”.

The pictures in this book are incredibly intimate and Sokhin has been given extraordinary access. He says he still marvels at the openness and friendliness of the women who have suffered so horribly. “It was really surprising to see how in some very difficult, traumatic situations women still accept foreign men with a camera to come into their houses or photograph them in the hospitals”.

Sokhin says he never approached a woman on his own and was mindful of the traumas these women had suffered. There was always a social worker, or someone from the NGO, or a local human rights defender with him who would also act as a translator.

Often it was a slow process, but Sokhin was patient. “When a woman is raped and she is in shock you can’t just come in and take the picture, even if she allows it. I didn’t want to take advantage of a situation that she might not understand. So sometimes I would come back the next day or a few days later, talk to her and explain again what I was doing”. He says there were instances when a woman had signed a release form approving the use of her image only to change her mind later on. “I had to pull some images from the project, but I respect that it is their right to remove the image, and I had no issue at all in meeting those requests”.

PNG is one of the last islands in the region where primitive traditions still exist in the remote villages. Sokhin tells when he was in the highlands he met a woman who was accused of being a witch and of killing a young boy in her family. “The family was hunting this woman who was on the run. We’d arranged to meet her through her brother. He’d told me he didn’t want to meet in a public place – she had just left the hospital because the family wanted to kill her there, and she was injured. So we were to meet in a remote location. So I arrive at the meeting place with the human rights defender who was working with me, and a driver, who turns out to be from the clan that is looking for her! Of course we had no idea”. Luckily the woman remained concealed and Sokhin was able to renegotiate with the brother to meet with her at another time. “These things happen,” he says, but it was a harrowing experience.

Being in challenging situations is all part of the job, says Sokhin who reveals gang members attacked him on the street several times and once in the early part of his project he arrived at a settlement unannounced and was chased away; “I was naïve, and didn’t make that mistake again”.

He also experienced police brutality first hand. Happening upon a group of policemen beating a man suspected of sexual assault, Sokhin automatically began taking pictures. “The police saw me and asked me to delete the photographs. I refused, so they shot above my head. Everyone ran away and I was arrested. So I had to delete the photos, and after that they released me”. He tells that later he recovered the pictures. “There’s software for that,” he grins.

After three years and multiple trips to PNG Sokhin feels that his work on this story has now come to a natural close with the release of his book “Crying Meri” which was funded through Kickstarter and published under the FotoEvidence imprint.

With the release of the book come new opportunities to continue the conversation and there are numerous international exhibitions planned for “Crying Meri” including one organised by ChildFund Australia, which is to open in Canberra on 2nd December at Parliament House. In New Zealand, Amnesty International also has events planned with a book launch on the 5th of December in Auckland and a Human Rights Breakfast and book launch in Wellington the following day.

Through “Crying Meri” Sokhin has been able to shed light on a story that few outside PNG had any understanding of and his work has also undoubtedly contributed to alter the perception of domestic violence in that country. His photographs have been used widely by agencies advocating for a shift in the law and images from Crying Meri have appeared on placards carried in the streets by protestors calling for an end to violence against women. In 2013 the PNG Government abolished the Sorcery Act that protected those accused of sorcery-related violence, including murder, and also instituted the first Bill to criminalise domestic violence. Steps in the right direction, but there is a long way to go before these reforms resonate at a deep cultural level.

In “Crying Meri” the terror the PNG women face is told in three chapters – Danger on the Streets; Danger in the Home; and Danger in Superstition. Sokhin’s book provides indisputable evidence of the atrocities and it is a vital document in the fight for reforms and cultural change. But as journalist Jo Chandler, who has worked closely with Sokhin, and is the author of the book’s introduction, says “What’s needed is a justice system which is trained, equipped, funded and compelled to provide safety for vulnerable citizens and enforce the law; national programs that work with men and boys to build respect and change abusive norms; social services and safe houses to release women from being trapped in abusive circumstances; medical and psychological support for victims of abuse; access to legal support; power structures that include and support women”.

Some of the most moving moments in this book are found in Sokhin’s diary entries that are accompanied by Polaroids. Next to a photograph of a woman named Julie, Sokhin writes: “Julie’s prosthetic leg – Julie’s father chopped off her leg when she was nine months old. “I don’t remember it myself, but people say that my father had a fight with my mother and he chopped off my leg during the fight,” said Julie. “Mum brought me to the hospital and never came back. When I was 17, I went to Lae hospital to make a new false leg. Raskols attacked me on the street and raped me. I got pregnant then. I love my son. He is everything I have”.

In conclusion Sokhin says that while he hopes his photographs may contribute to cultural change, “what is more important for me is to see an individual helped. I know of a few women whose lives changed because someone saw my photographs and assisted them. That’s an achievement I’m very proud of”.

BOOK

Crying Meri

Vlad Sokhin

Published by FotoEvidence

97 colour images/127 pages