The 33-year-old Italian photojournalist, winner of this year’s International Committee of the Red Cross Humanitarian Visa d’Or, Alfredo Bosco investigated between 2018 and 2020 in the state of Guerrero, Mexico. Where daily life is marked by violence and drugs. The inhabitants form self-defense groups, sometimes criminal ones, to face the cartels.

Why did you choose this subject on Guerrero?

“To tell the truth, it was one of my very good journalist friends, Pierre Sautreuil, with whom I had worked in Donbass, Ukraine, who discovered this story of self-defense militias in the state of Guerrero. From Guerrero, I only knew Acapulco. But when I got there, I realized that there was material for a much longer reportage. So I decided to continue on my own, discovering this war between traffickers. In the end, I had an assignment from Le Figaro, last year at Visa pour l’Image I had met the iconographer of the magazine. I was joined by one of their journalist, Vincent Jolly. ”

How long did you stay there?

“I’ve been there five or six times. Sometimes two months, sometimes ten days. It was not possible to go to the villages unexpectedly, because they are guarded by criminals. So you had to prepare well for your visit and keep in mind that, even though there is no front line, the state of Guerrero is at war. You should not underestimate the place you are going to. ”

How did you find local contacts for such a sensitive subject?

“We first relied on a French correspondent in Mexico, who spoke perfect Spanish, because there was a language barrier. Then, we met victims, victims’ associations, people in contact with the police. But like everywhere, it was especially necessary to spend time with the people. For example, I have been to Rincon de Chautla four times, the village where the police decided to train children and women to fight. The locals appreciated that I was really interested in their history. I chatted with them a lot to make them feel comfortable, although it’s never completely possible with a camera. The important thing is to be polite and respectful. ”

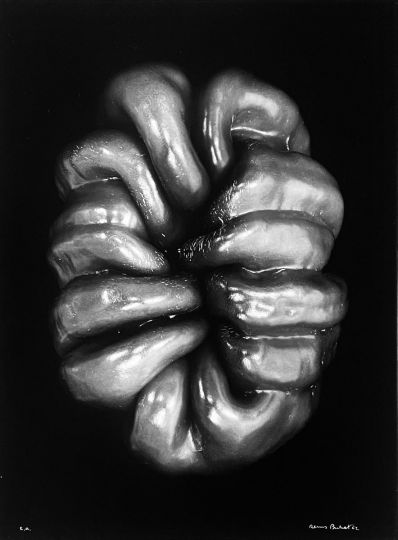

Your photos are sometimes difficult to view. Why this choice ?

“I fight with myself because I don’t want to aestheticize violence, but at some point you have to show it to understand it. I know my photos can be hard to see – so much so that they are sometimes unpublished. But the main thing is that they respect men. When I photograph bodies, I try not to show the face. ”

How do you deal with this violence as a person?

“It was during the earthquake in Haiti in 2013 that I realized I was capable of doing this kind of reporting. Maybe also because I am from southern Italy and have seen a lot of burials and dead people in my life. ”

How did you ensure your safety?

“I always had a GPS tracker that allowed people in Mexico City to track my location. I knew that if they did not hear from me at the end of the day, they would take act. You have to show people that you don’t want to hurt them, don’t stay too long, don’t talk too much, don’t be too expressive. Finally, you have to rely on local journalists who give good advices. According to RSF, Mexico is the deadliest country in the world for reporters. In fact, Mexican journalists only write “notes”, very factual short stories. They are often intimidated, some cannot live in the city where they work and have secure homes. You have to be careful not to endanger them. “

Do people understand what you are doing?

“Usually no. They don’t understand why I take pictures of this or that. For them, my job is less concrete than that of a print journalist. ”

Are you optimistic about the future of this state?

“Not at all, especially with the health crisis. The dynamics of Guerrero are similar to those of my home region, southern Italy. There, with the Covid-19, the little people, especially the traders, are in trouble and need money. And when the bank or the state doesn’t give you money, you go look for it elsewhere. Thus, the crisis encourages crime. I think it could be the same in Guerrero. In addition, the price of opium has fallen over the past two years and no longer allows the cartels to make enough money to their liking. The Covid-19 is therefore an opportunity for them. ”

Are you done with the Guerrero?

“I feel like I need to wrap up the job. I would like to add a part on the laboratories where traffickers make heroin. It is very difficult to get there and sometimes you have to negotiate three months to get into it, if only ten minutes. There is also a whole other problem that I would like to address: the gold mines in the region. They constitute a potential market for criminal groups. ”

Audrey Duquenne and Julien Francois

https://www.visapourlimage.com/