The photographs of the pictorialist movement are among the most spectacular works of art in the medium’s history. The Phillips Collection brings over 120 of these celebrated images to Washington, D.C. with the exhibition TruthBeauty: Pictorialism and the Photograph as Art, 1845–1945. The exhibition, drawn from the George Eastman House Collections, chronicles pictorialism from its inception through its impact on photography today. The Phillips is the final stop on the international tour of the critically acclaimed exhibition, organized by George Eastman House and Vancouver Art Gallery.

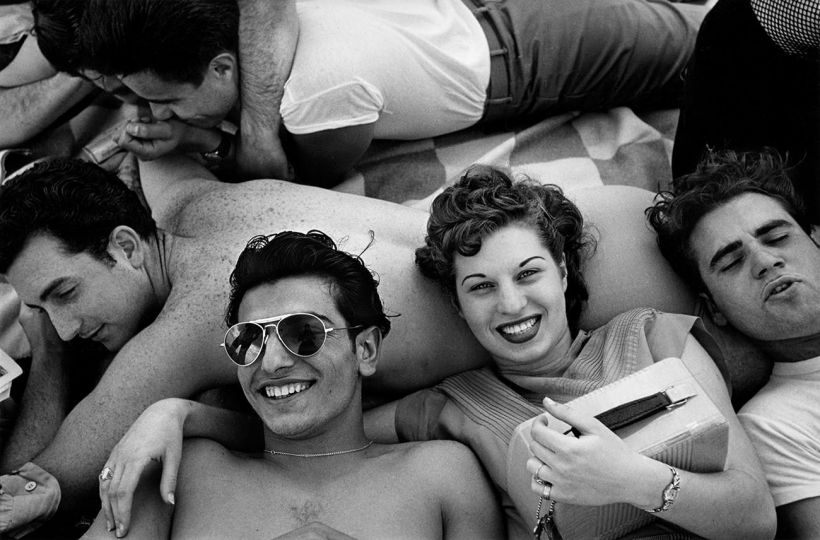

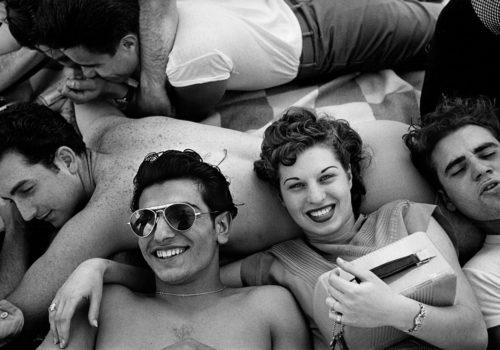

Like impressionism, which challenged the traditions of painting, pictorialism strove to expand the possibilities of photography beyond the literal description of a subject. Abandoning the camera’s ability to produce images in sharp detail that mirrored reality, pictorialist photographers instead used specialized printing processes to painterly effect to show that photography could be a vehicle for personal expression rather than factual description.

“The breadth and strength of this astounding collection of photographs speaks to the international vibrancy of pictorialism during the late 19th and early 20th centuries,” says Dorothy Kosinski, director of The Phillips Collection. She added, “Moving beyond the idea of the camera as a purely mechanical device, pictorialist photographers opened up a new world of artistic expression that had a profound impact on subsequent developments in modernist photography.”

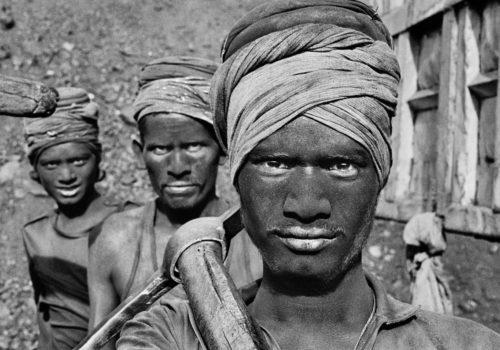

Pictorialism was simultaneously a movement, a philosophy, an aesthetic, and a style. Using soft focus, dramatic effects of light, unusual camera angles, suppression of detail, and bold technical experimentation, pictorialist photographers asserted the primacy of the photograph as an object of beauty. Through photography clubs, exhibitions, and journals, the movement spread from Britain to Europe, Asia, Australia, and North America.

TruthBeauty details how pictorialism arose in the late-19th century out of a desire to treat photography as an art form as important as painting and sculpture. It takes an expansive look at its sources and its legacy, considering practitioners from photography’s earliest years, who pictorialists would later claim as their spiritual ancestors, to its persistent practitioners, and its rarely recognized but seminal influence on photography today.

The exhibition also examines the generation of photographers who continued to meet pictorialist ideals long after the movement had concluded, featuring some surprising early work by Ansel Adams and Edward Weston, on whom the influence of pictorialism is not generally recognized. In addition, a broad historical selection of pictorialist journals such as Camera Work is included, underscoring their importance to the international dissemination of pictorialist ideas.

The range of the photographs featured in the exhibition provides a rare opportunity to examine the signature printing processes and technical innovations used by pictorialists. Prints made from single negatives in platinum, gum bichromate, and gelatin silver by photographers such as Alvin Landgon Coburn, Gertrude Käsebier, and Paul L. Anderson reveal how the printing process was a fundamental tool used for interpreting a subject and enhancing the aesthetic experience of it.

Pictorialism was a direct repudiation of the growing ease and popularity of photography in the late 19th century. George Eastman’s invention of the Kodak camera ushered in a new era that made photography more affordable and accessible. The company’s memorable motto, “You press the button and we do the rest,” was the complete antithesis of the pictorialist ideals. Their disdain for such an amateur approach to photography was characterized in the first issue of American Amateur Photographer, which stated, “We very much fear that…photography…has been degraded to the level of a mere sport, and many take it up as they do lawn tennis, merely for amusement, without a thought of the grand and elevating possibilities it opens up to them.”

Although the pictorialist aesthetic maintained a presence in advertising, popular portraiture, and in some amateur circles, its prominence was largely over by the end of World War I. The War and its aftermath left artists struggling to adjust to a new political, social, and economic order. Key aspects of pictorialist photography, however, have continued to be influential in contemporary practice more than 100 years since the movement began. The affirmation of the photographer as an artist, the drive toward an art of personal expression, the manipulation of the print as a carefully handcrafted object, and the elevation of photography to an art form are all hallmarks of the pictorialist legacy.

Until 9 January

Truth Beauty: Pictorialism and the Photograph as art,1845–1945

Coburn and the Photographic Portfolio

Phillips Collection

1600 21st Street, NW

Washington, DC 20009