This exhibition has been canceled, postponed or can only be seen by appointment: we have decided to show it to you!

March 24th was Edward Weston’s birthday, and as I look around the inventory I see we have a number of his photographs, not just one or two… an embarrassment of riches, if you will. We also have a couple of his son Brett’s most popular images, in rare, true vintage form. I wanted to show them off via posts to our Facebook and Instagram accounts, but this being the anniversary of Edward’s birth I thought a full-fledged website exhibition would be in order.

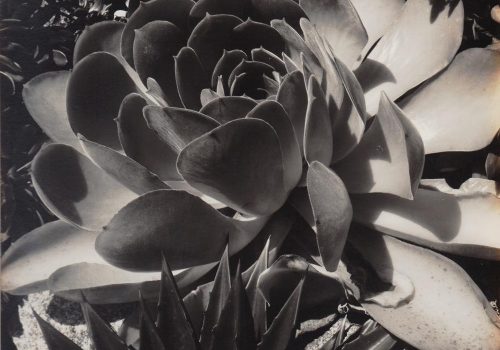

Although we mostly think of Edward Weston as a west coast, Point Lobos kind of guy, his roots lie elsewhere…in Highland Park, IL to be precise. When he was sixteen, his obstetrician father, gave him a camera, and the following advice: Do not stay too far away from your subject matter, or it will seem too small. This was excellent advice which Edward usually heeded, and to great effect. His credo was to “make the ordinary look extraordinary”. And, toward that end he made sure there was a close and tension-filled relationship between the edges of his subject and the edges of the picture’s frame.

He moved to California and opened a portrait studio in 1911 in Tropico, CA ( later to be called, Glendale). He photographed the well to do with soft edges, with an atmosphere suffused with glowing light. There was a touch of John Singer Sargent in this work, but he soon lost interest in it as he felt it had become too formulaic.

In 1921 he sets out for a trip to New York to meet Alfred Stieglitz, to show him new work, which had become very hard-edged and somewhat minimal, and hopefully get some guidance from him. On his way there Weston stopped to photograph the Armco Steel Works, in Middletown, OH. These pictures were to change his life. These images were greatly admired in New York not only by Stieglitz, but also by Paul Strand, Charles Sheeler, Georgia O’Keeffe, and others. When Weston headed back west, he was disappointed that Stieglitz hadn’t shown the overwhelming enthusiasm Weston craved, and thought was his due. But his artistic way was clear…no more pictorial photographs…Weston was now interested only in discoveries, and intensity.

On July 30th, 1923, Weston, his son Chandler, and his paramour, the photographer and leftist activist, Tina Modotti boarded a steamship for an extended stay in Mexico. His wife, Flora, and their 3 other sons, Brett, Neil, and Cole waved goodbye from the dock. It was the start of Edward’s big life adventure, both photographically, and romantically. His reputation preceded him, and when he arrived in Mexico Tina set up a show for him in one of the better galleries, which opened soon after his arrival. He was welcomed into a select group of artists who represented what was called the Mexican Renaissance. This group included Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco, Jean Charlot, Frieda Kahlo, and of course, Tina Modotti. Edward began to immerse himself in the dark side of Mexican culture, as seen through its objects which seemed to brood in sunlight and in shadow, and death seemed never far away. Mexico was a long way from sunny southern California. The dinner conversation was intensely philosophical, and political within the group. Weston became more and more loquacious, and more and more at ease.

Edward and Chandler returned to San Francisco at the end of 1924. In 1925 Edward returned to Mexico with Brett instead of Chandler. When they arrived back in Mexico, Brett embarked on a crash course in photography with his father. The student excelled. But Weston’s relationship with Modotti was beginning to fall apart, making their continued stay in Mexico untenable. In 1927 it collapsed. Edward and Brett returned to Glendale, and Edward organized a joint exhibition of his and Brett’s Mexican work, at the University of California. Remarkably, Brett was only 15 at this point. The show was well received.

When Weston and Brett returned to Glendale, Edward brought with him the belief that objects contain, on their surface and within, strong elements of a kind of felt knowledge that the camera could lay bare…in a sense he was following his father’s initial advice about getting in close to his subject. Rather than worrying about rules of composition he would proceed with bringing to bear what he referred to as, “the strongest way of seeing”. Southern California objects were not the same as those more ritualistic, folk art inspired objects of Mexico. They were lighter, brighter and resonated in different ways. But Weston’s scrutiny was the same, he used the camera in the same, investigative manner. As he said, “The camera should be used for a recording of life, for rendering, the very substance, and quintessence of the thing itself”. The thing itself…think about that!

How much do we really know about shells, or seaweed, or rocks. How carefully have we scrutinized them in all their variety? Weston was very taken with such pursuits.

And what about green peppers…the common bell pepper…what secret does it/ they hold other than an infinite variety of forms? Weston had been photographing peppers as early as the summer of 1927. Can we assume then that there were 29 other peppers photographed between that first 1927 pepper and the apotheosis brought about by Pepper #30 in 1930? #30 was a continuation of Weston’s approach, in that it used the same tension, between the edge of the object and the edge of the frame of the image, that existed 5 years earlier in the well known nude portrait torso of Neil. This tension was a signature element of Weston’s object pictures. It broke new ground, however, with the inclusion of a tin kitchen funnel, within which the pepper was nested. It was a brilliant discovery.

The vortex of the funnel was a hard space to read, and it eliminated the difficulty afforded by the picture’s base, and its background. The result is a formalist sculpture…one that you could eat! And he and his pepper partner, Sonya Noskowiak, did just that.

John Szarkowski, in his excellent critical photographic anthology, “Looking at Photographs”, tells the tale of a drawing teacher who was trying to get his students to use the whole page for their efforts. He said, that “a peanut in the bottom of a barrel was merely a spot, whereas a peanut in a penny matchbox, was a piece of sculpture”. Weston, to be sure, was the master of the matchbox.

If you are interested in more information about Edward Weston’s work, here is a link to a fine bibliography blog, by Paul Hertzmann, Susan Herzig, and Paula B. Freedman. Edward Weston Bibliography

– Alan Klotz.

Alan Klotz Gallery

740 West End Ave #52

New York, NY 10025