Mitch Epstein : America in light and shadow.

Mitch Epstein is a major figure in contemporary photography. Through his large-format images and mastery of color, he explores the interplay of landscape, power, and industry, documenting the profound transformations of the American territory.

His work oscillates between the personal and the political: Family Business (2003) chronicles the collapse of his family’s business in a declining industrial America, American Power (2009) examines the impact of the energy industry on the environment, while New York Arbor (2013) celebrates the resilience of trees amidst urban chaos. Winner of the Prix Pictet in 2011, Epstein offers a critical perspective on the contradictions of progress.

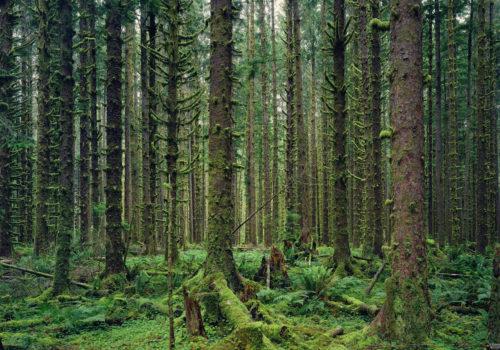

In his exhibition American Nature, on view at the Gallerie d’Italia in Turin until February 19 as part of the EXPOSED Torino festival, he confronts the raw beauty of untouched landscapes with the marks of human intervention, continuing his exploration of the coexistence between nature and civilization.

Between contemplation and activism, Epstein probes the memory of places and the fragility of life, tracing through his lens the lines of tension between past and future.

Website : www.mitchepstein.net

Instagram : @mitch_epstein

What was your first photographic trigger?

Mitch Epstein : It was when I was 16 years old. At the time, I was a student at a traditional boarding school in New England, Massachusetts, and I took on the role of editing the high school yearbook for my school. It was a very traditional institution, but the time we were living in was anything but traditional. It was during the Vietnam War, the first Earth Day had taken place, and there was a growing focus on environmentalism and social issues like racism in America. I wanted the yearbook to challenge some of these established traditions, and I sought photographers who could work against the grain of what was typically expected. When I couldn’t find many, I decided to take matters into my own hands. I embarked on an independent study and began creating images myself. That experience was the first real trigger that led me to photography.

Is there a man or woman of image who inspired you or still inspires you?

Mitch Epstein : My first significant teacher in photography was Gary Winogrand, back in 1972. He taught me to unlearn much of what I thought I already knew. The process of relinquishing preconceptions about art was disorienting but transformative. That destabilization remains with me to this day—your preconceptions are not your allies in the creative process. I owe a great debt to his direct, no-nonsense approach.

Is there an image you missed taking, or an image by someone else that you wish you had created?

Mitch Epstein : I don’t think that way. When I am moved by another artist’s work, whether in photography or another medium, I consider how I might draw inspiration from it and integrate certain ideas into my own practice. Regrets about missed opportunities don’t factor into my thinking. That perspective, I believe, has helped me maintain a healthier approach to my work.

Can you think of an image that particularly moved you?

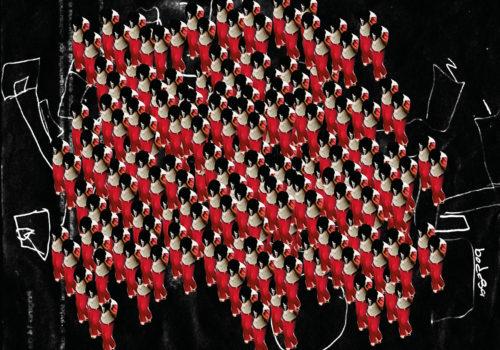

Mitch Epstein : Last week, I saw a drawing by David Hammons, the African American artist, in Venice at the Pinault Collection. It was part of an exhibition contextualized with Julie Mehretu’s work. Hammons’s creations consistently excite me; they challenge me to see the world from a different perspective.

And one that made you angry?

Mitch Epstein : I would say, what disappoints or frustrates me is when attention is given to work that feels mediocre or shallow. In photography, this is partly due to the overwhelming volume of images we’re surrounded by. Some work appears derivative, unoriginal, or overtly commercial—prioritizing marketability over authenticity. While I wouldn’t say I’m easily angered, I do find such instances disappointing.

Is there an image that changed the world?

Mitch Epstein : No single image comes to mind as having changed the world. While art and imagery can unsettle, inspire, and lead to transformation, the world itself is so vast and multifaceted that attributing change to a single photograph feels reductive. That said, I firmly believe in the power of art to move people and provoke meaningful shifts. Without that belief, I wouldn’t practice it myself.

Is there an image that changed your world?

Mitch Epstein : The images that have truly changed my world are the ones that don’t reveal themselves to me too quickly. One example is a photograph by Robert Adams, a small print my wife gave me when I turned 50. I’ve come to greatly respect Adams as an artist, colleague, and friend.

The photograph shows a tree that feels abandoned, surrounded by scattered debris, perhaps on the edge of a highway. It seems weathered and out of place, as though it has endured hardships. At first, I didn’t fully connect with the image, but over time, living with it, I’ve come to appreciate its depth.

I find that the works which don’t immediately resonate often become the most enduring. They demand time and reflection, and in doing so, they leave a lasting impression.

What interests you in taking pictures?

Mitch Epstein : Photography helps me clarify my understanding of the world and my relationship to it. It allows me to explore unique perspectives that only photography as a medium can offer—qualities that other art forms might not achieve in the same way.

What is the last picture you took?

Mitch Epstein : The last picture I took was on my iPhone yesterday during the installation of an exhibition. Workers were lifting the top of a vitrine case in a large room with suction tools, and I captured that moment. It might have been one of my final shots of the day.

But I also take pictures with my eyes—almost like a memory or a mental notebook. Using my phone to take pictures keeps me in practice, as I still make decisions about framing and the relationships within the frame. This year, for the first time, I dedicated myself to photographing a single subject over the course of the year with my phone. I explored what kinds of pictures the phone could capture that other cameras couldn’t, especially in terms of positioning and accessibility. The phone allowed me to seamlessly integrate photography into my day-to-day life without interrupting other work. While these images might never be formalized as art, the process itself was an opportunity to experiment and connect with a subject in new ways.

Do you have a photographic memory from your childhood?

Mitch Epstein : Yes, a picture my father took of me with a Minox camera when I was eight years old. I was standing in front of a camp cabin with a symbol that resembled a Native American motif—one that also bore an unfortunate resemblance to the swastika. That experience and that camp left a lasting impression on me.

What is the essential quality to be a good photographer?

Mitch Epstein : A good photographer must be educated in every sense and remain open to the unknown. Discipline, genuine passion for the craft, and a willingness to embrace risk and failure are also crucial. Loving the work itself is indispensable.

What makes a good picture, in your opinion?

Mitch Epstein : That’s a tough question because my idea of what makes a good picture is always evolving. It changes as I encounter new images that challenge my perspective. However, at its core, a good picture requires a certain tension between form and content—a balance where the form effectively articulates the content.

The impact of an image often depends on how this relationship is handled. Even seemingly banal subjects can become powerful and evocative if framed in a compelling way. Ultimately, the ongoing “wrestle” between form and content is essential to creating a successful image.

If you could photograph anyone, who would it be?

Mitch Epstein : I don’t have a specific person in mind, and it wouldn’t necessarily have to be someone famous.

Can you name an essential photobook?

Mitch Epstein : There isn’t just one essential thing—there are many. So many things can feel indispensable. But for me, I don’t get overly attached to anything. If I’ve read and appreciated a book, losing it doesn’t feel different from having a meaningful relationship with someone who has passed; the connection remains. What matters most is the depth of that connection, not material possession. I’m not a collector. Art is about the experience, and I can always revisit it in a museum or exhibition. Even my library is limited by space; I keep books that I’m not yet ready to fully understand. For instance, I initially didn’t fully grasp Mika Schmidt’s work on Berlin’s transformation. But over time, as I engaged more deeply, I came to appreciate it more.

Could you describe your creative process?

Mitch Epstein : My creative process starts with a cup of coffee and balancing the larger purpose of my work with the practical need to sustain it. It’s about creating an environment that challenges me, whether in the studio or out in the world, and allowing time to ground myself in the direction I’m heading. I don’t lock myself into a fixed path; instead, I let the work evolve as I create it. For instance, in this exhibition, I began by studying historical frontier and logging images, not expecting to incorporate them into my project. But through being open to new ideas, I decided to include a piece on Darius Kinsey, inspired by these photos.

A similar process occurred with my Forest Waves project. For years, I’ve used vibrational sound therapy as a healing tool, influenced by my acupuncturist’s use of Chinese gongs. After learning more about a musician I worked with, I had the idea of bringing multiple musicians into the forest. These ideas come together through direct life experiences, not from pre-conceived plans. When I go out to photograph, I often start with a destination in mind—a tree or a trail related to the project—but I remain open to what presents itself along the way. If the light or conditions aren’t right, I adapt and look elsewhere, knowing that inspiration can come from unexpected places. My process isn’t formulaic; it’s ever-shifting, much like the real world. This fluidity is what makes photography so compelling: it’s a way to engage with real-time, tangible experiences, and there’s no single way to approach it, which is both challenging and exhilarating.

What was the camera of your childhood?

Mitch Epstein : My first camera was a Kodak Brownie.

And the one you use today?

Mitch Epstein : For the past 15 years, my principal camera has been an 8×10-inch wooden and metal field camera, a Phillips. It’s lightweight, minimalistic, and designed by a Michigan dentist. Though no longer in production, it’s perfectly suited to the kind of pictures I like to create.

Who would you like to be photographed by?

Mitch Epstein : Thomas Struth comes to mind—his portraits are beautiful and profound.

Any recent folly?

Mitch Epstein : Perhaps some of my long-winded answers at the press conference. Beyond that, there are many, but none come to mind immediately.

What would you have been if not a photographer?

Mitch Epstein : As a child, I dreamed of becoming an astronaut, but I never fully understood what it would take to achieve that. Looking back, I’m sure I wouldn’t have made it. However, this exhibition shows that I still have the chance to explore things beyond my photography. I’ve always had a strong interest in cinema and film, and for a decade, I collaborated with my first wife, Mira Nair, on film projects. I also made two films about my father, which still hold my attention. I’m sure I will continue to pursue other artistic endeavors outside of photography.

Being an artist, I believe, was my destiny. I’ve never questioned it, and I have no regrets. But being an artist also means accepting uncertainty, unpredictability, and struggle. Even after 50 years, those challenges remain. The process is never fixed; it requires embracing doubt and ambiguity, which is what allows progress to happen. This approach isn’t for everyone—it takes a toll. You need to stay sharp and flexible, adjusting to the unpredictability of the work and what happens to it afterward. The questions of how to share it and what comes next are constant.

Someone recently asked me, “What’s next?” But I don’t know. The hardest part is staying focused on the present. The present moment will guide me to what’s next, but if I’m thinking ahead, I’m not truly grounded in the now.

What kind of question could get you off track?

Mitch Epstein : A question that holds a mirror to what I don’t know.

Which place do you never tire of?

Mitch Epstein : Home.

Are you active on social networks?

Mitch Epstein : I use Instagram somewhat actively, but in a measured way. I mostly handle it myself, not through my studio, and I enjoy the connection with an audience I don’t know. That said, navigating the changes on the platform isn’t always easy. I try to keep Instagram less about promoting my work and more about the simple act of sharing a photo a day, much like Stephen Shore’s philosophy of “an apple a day”—just one picture, not ten or twenty. It provides a kind of discipline, even though sometimes nothing particularly interesting happens.

However, there have been moments when Instagram proved useful. For example, once while working with my 8×10 camera near a defunct copper mine in Arizona, I realized it was late afternoon and I hadn’t taken a photo yet. I pulled out my phone, took some pictures of a weathered poster board, and noticed evocative words that inspired me to grab my 8×10 and make a more considered shot. Similarly, during a visit to Mount Rushmore, I wasn’t permitted to photograph that day, but I used my phone to scout the location. When I saw the way the moving clouds and water created a metaphorical effect on the Presidents’ faces, I decided to sneak in with my 8×10 and make the shot.

For me, Instagram and my phone serve as a form of sketching, part of a larger artistic practice. It’s okay, but I do wonder how much I can share about exhibitions without overwhelming my audience. I’ve probably posted too much about this one. What’s most important to me in my work is giving equal attention to everything I do, as much as I can.

Color or black and white ?

Mitch Epstein : Both. I’ve intentionally created work in black and white, even though I’ve always been a color photographer and use color as a key part of my photographic language. When I started this project, the first images were black and white. However, in the series to be published by Steidl, there will be some black and white photographs as well.

More daylight or studio light?

Mitch Epstein : I prefer daylight.

Which city is, regarding to you, the most photogenic ?

Mitch Epstein : I don’t think in terms of what’s photogenic. New York has held my visual and human interest for over 50 years, since I first arrived in 1972. I’ve returned to it periodically as a subject in my work, most recently with a trilogy exploring the intersection of nature and the urban landscape—New York, Arbor, and Rocks and Clouds. I chose to shoot these in black and white because I wanted the images to feel contemporary, while keeping the color from dominating.

New York has maintained my long-term interest, but I don’t view it as simply photogenic. The city’s vastness makes it inexhaustible; you could spend a lifetime photographing it and create endless series. It’s like a forest in that way. Ultimately, it’s about the moment—the light and many other factors shape the outcome.

As for God, if He exists, I wouldn’t ask Him to pose or take a selfie. I’m not into selfies or posing people, and I don’t believe in personifying God. I also see the selfie culture as a significant cultural issue.

If I could organize your ideal dinner party, who would sit at the table ?

Mitch Epstein : Well, I could invite people who are smarter, more entertaining, and more attractive than I am, which would make it fantastic—a dream. But if I were to make a list, I’d need to sit down and think about it, and even then, I’d feel a bit shy. I’m always interested in being around people who have knowledge.

An image which represents the current state of the world ?

Mitch Epstein : Maybe in the image of somebody taking a selfie.

If you had to restart everything, would you do it the same way?

Mitch Epstein : Yes, I would. Even during difficult times in my life, I’ve gained from those challenges. Marriage and divorce are painful, but if we’re fortunate and have the capacity, we come out the other side with a perspective that’s valuable. So no, I wouldn’t change anything.

A last word ?

Mitch Epstein : Thank you so much. That was fun.