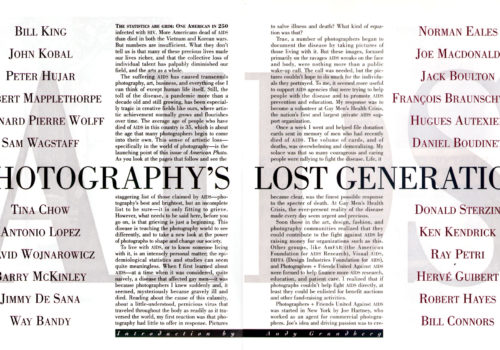

The statistics are grim : one american in 250 infected with HIV. More Americans dead of AIDS than died in both the Vietnam and Korean wars. But numbers are insufficient. What they don’t tell us is that many of these precious lives made our lives richer, and that the collective loss of individual talent has palpably diminished our field, and the arts as a whole.

The suffering AIDS has caused transcends photography, art, business, and everything else I can think of except human life itself. Still, the toll of the disease, a pandemie more than a decade old and still growing, has been especially tragic in creative fields like ours, where artistic achievement normally grows and flourishes over time. The average age of people who have died of AIDS in this country is 35, which is about the age that many photographers begin to come into their own. This sense of artistic loss – specifically in the world of photography – is the launching point of this issue of American Photo.

As you look at the page that follow and see the staggering list of those claimed by AIDS – photography’s best and brightest, but an incomplete list to be sure – it is only fitting to grieve. However, what needs to be said here, before you go on, is that grieving is just a beginning. This disease is teaching the photography world to see differently, and to take a new look at the power of photographs to shape and change our society.

To live with AIDS, or to know someone living with it, is an intensely personal matter; the epidemiological statistics and studies can seem quite meaningless. When l first learned about AIDS – at a time when it was considered, quite naively, a disease that affected gay men – it was because photographers I knew suddenly and, it seemed, mysteriously became gravely ill and died. Reading about the cause of this calamity, about a little-understood, pernicious virus that traveled throughout the body as readily as it traversed the world, my first reaction was that photography had little to offer in response. Pictures to salve illness and death? What kind of equation was that?

True, a number of photographers began to document the disease by taking pictures of those living with it. But these images, focused primarily on the ravages AIDS wreaks on the face and body, were nothing more than a public wake-up call. The call was needed, but the pictures couldn’t hope to do much for the individuais they portrayed. To me, it seemed more useful to support AIDS agencies that were trying to help people with the disease and to promote AIDS prevention and education. My response was to become a volunteer at Gay Men’s Health Crisis, the nation’s first and largest private AIDS support organization.

Once a week I went and helped file donation cards sent in memory of men who had recently died of AIDS. The volume of cards, and of deaths, was overwhelming and demoralizing. My solace was that so many courageous and caring people were rallying to fight the disease. Life, it became clear, was the finest possible response to the specter of death. At Gay Men’s Health Crisis, the ever-present reality of the disease made every day seem urgent and precious.

Soon those in the art, design, fashion, and photography communities realized that they could contribute to the fight against AIDS by raising money for organizations such as this. Other groups, like AmFAR (the American Foundation for AIDS Research), Visual AIDS, DIFFA (Design Industries Foundation for AIDS), and Photographers + Friends United Against AIDS were formed to help finance more AIDS research, education, and patient care. I realized that if photographs couldn’t help fight AIDS directly, at least they could be enlisted for benefit auctions and other fund-raising activities.

Photographers + Friends United Against AIDS was started in New York by Joe Hartney, who worked as an agent for commercial photographers. Joe’s idea and driving passion was to create an exhibition and auction of photographs called “The indomitable Spirit,” and to help him pull it off he enlisted Marvin Heiferman, Lisa Cremin, and a cast of literally hundreds of photographers, curators, collectors, dealers, writers, manufacturers, and editors. The photography community’s first organized response to AIDS, “The lndomitable Spirit” raised more than a million dollars. Joe died of AIDS in 1991, but Photographers + Friends continues to devise new ways to raise funds and consciousness.

After working with Joe and his organization, I realized that photography was capable of doing great things to help in the fight against AIDS. I also realized that it was shortsighted to think that photography as a medium could have little real impact on the lives of those living with AIDS. I overlooked my own critical tenet, that photographs exist not only as objects of aesthetic pleasure but also as instruments of cultural representation. Like it or not, photography was playing a role in forming the public’s perception of AIDS and people with AIDS. It took the critical analysis of AIDS activists, many of them members of ACT UP, to remind all of us that photographers were not innocent bystanders in the creation of AIDS folklore.

As writers like Douglas Crimp and Simon Watney have pointed out, representing AIDS as an incurable disease to which only gay men fall prey is doubly damaging: It takes away hope from those who are HIV positive, and it associates the virus with sexual preference rather than specific behavior. (Today, the greatest growth in HIV transmission rates in the United States involves heterosexual intravenous drug users, both male and female.) Photographs, alone or in tandem with words, can portray AIDS responsibly and accurately, or irresponsibly and inaccurately. They can do good or they can do damage.

Photographers are still struggling with the issue of how to represent the disease. For Nicholas Nixon, the descriptive powers of the medium are enough to redeem the dissolution of human life that he documented with his 8xl0- inch view camera. For Rosalind Solomon, representing hope within the context of traditional portraiture seemed the highest priority. For Brian Weil, traditional documentary strategies lead to meaningless voyeurism; his pictures, blown up to poster size and frequently accompanied by text panels, confound superficial readings and involve audiences’ full attention.

At the Ansel Adams Center in San Francisco, where I work and where the Weil show appeared last summer, the photographer spent several days talking with visiting school groups, and people with AIDS were enlisted to make Polaroid journals of their daily lives. The result was an exhibition that was not only educational in the best sense but also popular: Attendance for Weil’s show was twice what it had been for other shows during the year.

A dozen years into the AIDS epidemie, it is clear that photography has two important roles to play: As participants in a field deeply affected by it, we need to help finance the fight against the disease; as photographers and image shapers, we need to convey information about AIDS with sensitivity and accuracy.

As the list of photographers and their colleagues in this issue suggests, we have a special responsibility to those we have known, loved, and worked with to respond positively to AIDS. lgnoring it won’t keep anyone from getting it, and it won’t help find a cure.

Andy Grundberg is the director of The Friends of Photography in San Francisco.