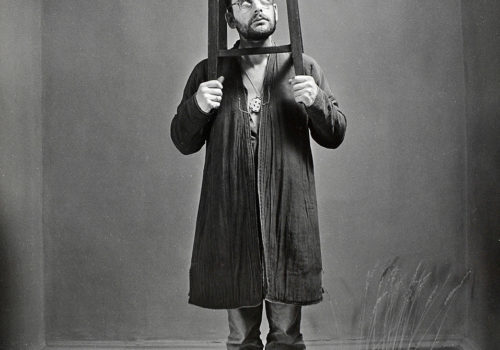

by Guennadi Maslov

It was not graffiti as we think of it. Rather very short phrases reminiscent of the party slogans:

WORK WHERE — ON EARTH. VEK-VAK. EATING IS TOXIC.

YOU ARE NOT THE EARTH AND COULD NOT BE IT. LENIN MEANS MITASOV.

In a rather orderly manner, the words were written with solid white oil paint on the countless red brick walls of the City of Kharkiv. Everybody knew who wrote them — a quaint, burly, local madman Mitasov. Aware of the threat of another visit to a psychiatric ward he would do it mostly secretly. Later he would deny everything but periodically ended up promptly arrested, beaten, and transferred to ‘Durdom’ the Psychiatric Hospital No36. But it was 1986, and the times were changing. The KGB and head-shrinkers were no longer interested in Mitasov the Madman. The communal workers were no longer paid to erase his philosophical logos. General Secretary Gorbachev was successfully completing the destruction of one of the most curious political formations in history — Planet USSR was on its last legs.

There was nothing very special about the City of Kharkiv with its 1.7 million inhabitants. Perhaps, just the fact that it was the fourth largest city of the Soviet Union, a hub of heavy industry, scientific research, and the epicenter of a large area in Eastern Ukraine which arguably could be named the largest ethnic melting pot of the whole empire. Practically everyone was a mix of something, with the most common blend consisting of Ukrainian, Russian and Jewish ingredients, at times complemented by sprinklings of Tartar, Polish, and Greek.

There was, however, something that even further distinguished the big grey city — it seemed to be a monumental incarnation of THE city of the late Soviet period. Photographers like to notice things. Kharkiv photographers noticed Kharkiv.

The process started in the early 1970s and lasted well into the ’90s. By now it has become customary to talk about the Kharkiv Photography School as a strong cultural phenomenon of those years. Seemingly out of nowhere there appeared a couple of dozens of fine art photographers who refused to follow the unwritten rules and seek the establishment’s approval of their art.

Photography in a totalitarian state is anything but unpredictable. Strange parallels can easily be found between the ways art photography evolved in so obviously different countries as fascist Germany, the socialist Soviet Union, and imperial Japan. The 20th-century regimes were fond of encouraging the photographic activities of the masses. But only up to a point — the point when the camera stops being a tool of the non-critical, optimistic depiction of reality and turns into a channel of skepticism and uncontrolled self-expression.

Even during the post-Brezhnev years, everyone knew that a phone call from the KGB and a polite invitation ‘to a short talk’ meant nothing but trouble. The man I met on a park bench in Shevchenko Garden was not much older than myself, a university student of 23—24. The combination of his casual dress and bad breath confused me. No, they did not want anything from me right then. No, of course, there was nothing really bad about belonging to the Semaphore Camera Club (how on Earth did you come up with a name like that?) but there was some information about some club members… and they would really appreciate ‘a signal’ about anything even potentially subversive. Especially if the signal came from a good student grooming himself for an important career as a professional linguist and interpreter. (Not just a photographer, they wanted to believe.) At that time almost no one carried business cards. The man did not write down his phone number but gave me a piece of paper and a pen to do so. “So call any time. Prepare to be helpful.” A sly smile. In the subway, when the passenger car doors open, a thin gap appears between the car and the platform. My hands probably trembled a little, when on my way home I rolled the paper into a small ball and dropped it into the gap.

In many ways, the new photography we worshiped was a reaction to the 50 years of Soviet propaganda. Practically all photographs published during those years were censored in order to become a part of the greater ideological effort. All images had to carry a very concrete message that favored the Socialist happiness of today, and the unstoppable movement of the country towards the Communist nirvana of tomorrow. Subjective or critical interpretation of reality, the celebration of individualism, or even exploring one’s own reflective experiences were considered suspicious and had to be cut short or channeled into the state-sponsored and state-controlled camera clubs. The ’70s were not as brutal politically as the bloody Stalin years. Not following the official line would not usually mean death or a labor camp sentence. Instead, the most disobedient artists risked losing their state benefits, their jobs, or even the ability to practice art. Many did.

In this context, the somewhat predictable but nevertheless explosive emergence of a group of brave and talented photographers impressed the public and saddened the authorities… Evgeniy Pavlov, Boris Mikhailov, Yury Rupin, Aleksandr Suprun, Oleg Malevany, Guennadi Tubalev, Aleksandr Sitnichenko, and Anatoly Makienko formed the now legendary Vremya (‘Time’) group in 1971. A series of ‘official’ and private exhibits followed to prove that a new page was opening in art and the public conscience. The taboo themes came out in the open: honest documentalism, formalist experimentation, images celebrating subjectivity and exploring the human condition, even the depiction of nudity!

The 1970s thundered by. There were arrests and professional sanctions, studio searches and divorces, crushed carriers and successful exhibits, criticism in the official Soviet press, and moments of glory in the pages of Western publications. The Vremya Group did not last long and dissolved to be replaced by others. But the group’s contribution is hard to overestimate — it is deeply felt in the works of the second wave of Kharkiv photographers who came onto the scene with less revolutionary kaboom but possibly with a deeper sense of conceptual interpretation of what was going on in the society.

The beginning of the ’80s looked optimistic: the government acknowledged the existence of problems and pledged to fight them. After Brezhnev’s death, in quick succession, each of the country’s leaders had his own ideas of the experiments to which the country should be subjected. Andropov came up with the strengthening of work discipline, resulting in ridiculous street arrests of people who the police deemed idle. Chernenko (when physically capable) introduced a bunch of bright endeavors including turning the North-flowing Siberian rivers southwards, increasing the number of years of compulsory schooling, and boycotting the Los Angeles Olympics. The age of Gorbachev started with the anti-alcoholic campaign and the loosening of some censorship.

Western books and magazines on fine art photography began to trickle into the country. It was really surprising for many to realize that although some Western art styles were reinvented in the isolated Soviet Union late and in a distorted fashion many artistic discoveries were far ahead of the ‘capitalist’ equivalents.

The light is dim in the mezzanine private gallery in Rustaveli Street. The Kharkiv intellectual beau monde are all present and awaiting the new star’s exhibit opening: photographer Sergey Bratkov has made it to his native Kharkiv from his new fame in Moscow. The dim lights are only natural: the power supply is rationed. But why are the main doors still closed? And where is the famous author and provocateur himself? Loud steps on the old wooden stairs below startle everyone. The crowd grows nervous: too many people would have to be arrested… And THEY don’t seem to arrest so much anymore… But it is Bratkov himself! He and five or six friends, each with a big wine bottle in their hands: Sorry, guys! They would not sell more than one bottle per person in that line on the corner…

The artists of the second wave were already aware of their belonging to a unique milieu. They were a little younger, somewhat better educated, considerably less scared of the authorities, albeit as bold in their love of the medium as ‘the elders’. They formed a few artistic groups that were united more by their dislikes than by any common ground. As the state was relaxing its grip even more, it became trendy to belong to non-conformist groups such as Gosprom, April, Contact — all being loose amalgamations of 6-12 male artists. (There were almost no professional female photographers at the time.) Gathering in private flats or small studios, consuming a lot of coffee and stronger beverages, critiquing each other’s works, and planning the next breakthrough exhibit were the groups’ routine activities. The author is proud to belong to a group of those days: A.Avdeenko, I.Chursin, I.Karpenko, V.Kochetov, I.Manko, M.Pedan, L.Pesin, R.Pyatkovka, S.Solonski, V.Starko… (I am certainly forgetting someone.) The more traditional artists continued to have more public opportunities but limited understanding of the trends evolving around them.

The mighty Soviet Empire was falling apart faster and faster. Did the photographers of Kharkiv realize they were among the active contributors to the process? Was the unwritten philosophy of Kharkiv Photography School a sublime revolutionary doctrine? Only on the intuitive level, I believe. And also taking into consideration that there was no Kharkiv Photography School at all. What happened in the 1970s and ’80s in a grey industrial Soviet city was a surprisingly potent burst of creative activity among the disillusioned and romantic (yes, romantic) group of young photographers. They came to be a part of the phenomenon by very different routes and never had a common (let alone concrete) aesthetic ground.

Our camera equipment was often primitive; our dreamy hearts were always trembling…

Long life to the panoramic ironies of Kochetov, the painfully poignant cityscapes of Makienko, and the sepia-toned fantasies of Chursin. Long life to Aleksandr Suprun, the champion of all possible FIAP awards, and his wonderfully lyrical montages. Was there anything artistically common between the merciless documentaries of Mikhailov and the hand-painted psychological satires of Pavlov and Shaposhnikov? Hardly, except perhaps the shared cultural undertone and the energy of talent.

We came together for a short time and then, led by our own aspirations, went our ways. The absence of a strong leader and the concentration of so many charismatic individualities in one place played their role. The more consistent and business-like of us never stopped and continued the energetic and often provocative pursuits somewhere else, often abroad. Some were a part of the phenomenon mostly because at that time it was fashionable to be a creative rebel. They did not really last as artists. For some, the “burst” was a time to charge their artistic batteries in preparation for future personal endeavors.

The smoke cleared long ago. The energy of the Kharkiv Burst lives on.

To learn more about the Kharkiv School of Photography visit the platform Kharkiv School of Photography: Soviet Censorship to New Aesthetics. The platform is a part of the Ukraine Everywhere program of the Ukrainian Institute and is dedicated to the promotion of the Kharkiv School of Photography achievements among the wider international audiences and its introduction to the all-European artistic context.

This essay was originally published under the copyright of the VASA Project and the author. Guennadi Maslov, a Kharkiv photographer in the 1980s, teaches photography at Blue Ash College, Ohio, USA

Guennadi Maslov