Unknown in the West, Albanese photography is perhaps one of the most important in the Balkans and maybe one of the most consequential in Europe.

The story begins with Pjetër Marubi, a supporter of Garibaldi who fled Italy and took refuge in the city of Shkodra, in the Ottoman Empire. He was a true pioneer in photography, opening his first studio there in 1850.

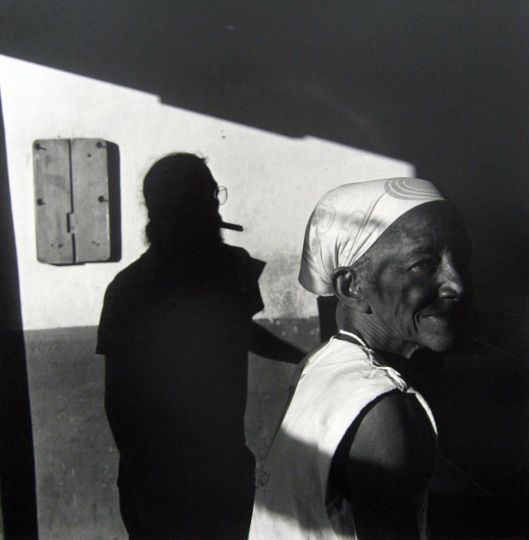

His business became an immediate success, attracting people from across Albanian society who came to pose in front of his camera. After his death, several generations of photographers would continue his work, providing ongoing witness to history and daily life there. These “light poets”, as Ismaïl Kadaré would call them, brought Albanian photography into the golden age that would last there until 1944, when the dictator Enver Hoxha came to power. The impressive gallery of portraits they left behind wavered between social witness and artistic observation. Their models posed in front of the same painted backgrounds that remained unchanged for decades, in settings resembling master paintings.

Re-emerging after 50 years of repression and isolation, this ethnological work reveals the different faces of Albania’s little known past, an ottoman Albania, independent, yet occupied by Mussolini.

Despite the oriental influences and the thousand kilometers that separate Shkodra from Frameries, Albanese photography from the early 20th century is strikingly similar to that of Belgian portraitist Norbert Ghisoland.

An exhibition by Loïc Chauvin, author of “Albania, face of the Balkans” and Christian Raby, Professor of Philosophy and Photography.

Until March 27

Le Botanique, Centre culturel de la Communauté française Wallonie-Bruxelles

236, rue royale

1210 Bruxelles