The Japanese photographer Yasuhiro Ishimoto who has died at the age of ninety was one of the leading figures in the renaissance of photography in Japan in the years immediately after the Second World War. Born in the USA he first entered Japan with his parents when he was three years old, his father was a farmer and in spite of his desire to become an engineer he began studying agriculture in high school. When the war with Manchuria threatened in 1939 his mother, as he had been born in the United States, succeeded in arranging for him to return to the US immediately following his graduation from high school, and thus he was able to avoid conscription into the army. Initially he continued his studies in agriculture in San Francisco. His studies were interrupted by the war and he was interned at the Amache Camp in Colorado. It was here that he first developed his interest in photography. Upon his release from internment he settled in Chicago as he was still forbidden by the US government to live on the coast as he had taken part in military drills while at high school in Japan; it was an intersection of arbitrary events that he was later to recognize as having been instrumental in his formative years as it made it possible for him to enroll in the New Bauhaus, Illinois Institute of Technology, in Chicago.

Upon arriving in Chicago, a city that was to have a major presence in his life thereafter, his initial impetus was to study architecture at Northwestern University. Bearing in mind the terrible destruction of the war years in Japan he thought it would be the most useful profession. However after a few months he elected to change his course of study and enrolled in the photography programme at the Institute of Design in 1948 where he studied with Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind. His remarkable gift was already highly developed and he was successful as a student winning much acclaim for his work. He graduated in 1952.

Ishimoto moved back to Japan again in 1953, and in that same year he made the series of pictures for which he is best known, of the Katsura Imperial Villa in Kyoto. Here he conflated his studies in photography in Chicago, (a programme set up by the great modernist Lázló Moholy-Nagy), with his innate respect for the traditions of Japanese art and architecture. Combining a modernist aesthetic with such traditional subject matter gave a depth and resonance to the pictures that is exemplary. The book, prepared with Kenzo Tange, and with the support of Walter Gropius, chose to present the structures as a modernist palimpsest and stripped away some of the more conventional aspects of the subject. It was an editorial choice that gave Ishimoto pause and he was to bear in mind in future projects the lessons learned in the process of editing the Katsura photographs. He revisited the project in later editions of the work and yet again in 1982 when he reinterpreted the villa in a majestic series of photographs in colour. His photographs have not yet been surpassed, they have become canonical, and the book remains amongst the most celebrated from its time.

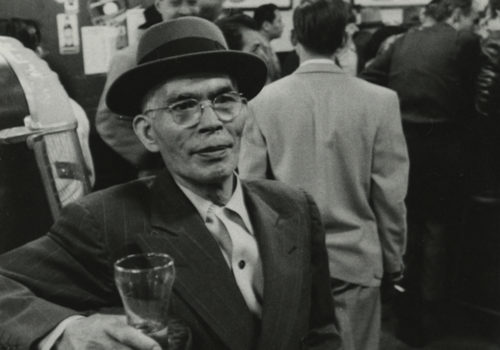

In the following years he maintained his American connections and was included in Steichen’s Family of Man exhibition at MoMA, a show that marked the zenith of a particular approach to photography and one that had considerable influence. He moved back to Chicago again in 1958 and began work on what was to become another highly regarded book. Working with assurance and with a spontaneity that was very different to the earlier work he made a portrait of the city as it was at the end of the nineteen-fifties. His quizzical, sometimes acerbic gaze is what gives the book its force and Chicago Chicago, published in 1969, cemented his reputation. He returned to Japan once more in 1961 and became a naturalized citizen in 1969.

The next years were taken up with a succession of teaching positions and a copious outpouring of work. He published many more books on subjects as widely varied as the celebrated Mandalas in the Toji temple in Kyoto, the pots of Lucie Rie, and a wide ranging study of Islamic architecture over the greater part of the historical and geographic range of Islam. He also made a significant body of work that explored purely abstract and non-camera methods of making photographs, perhaps in acknowledgement of his early exercises in photography at the Institute of Design and taking into account in his own works the earlier tradition of the photogram and related creative photographic techniques.

He was frequently called on by the celebrated architect Arata Isozaki to photograph his works, a long lasting collaboration that was of great benefit to both men. Amongst his later work his record of the reconstruction of the temples at Ise published in 1993, with an essay by Isozaki, should be noted. Only the second photographer to be permitted to record the structures he produced a beautifully measured set of images that are a fine complement to his work at Katsura. The two projects pay attention to works of architecture that stand at the very centre of Japanese culture.

Ishimoto was an extremely modest man, secure in the knowledge of his gift, and he went quietly about his work with little outward display. He took considerable pleasure in the craft of photography and was meticulous in the presentation of his work. His darkroom, where he printed his black and white photographs, was tiny, little more than a cupboard, but his prints were always of the highest quality. He preferred long, concentrated periods of activity, generating pictures around an idea and taking note of the changes of the society in which he lived. He recorded the way things were, looking with a fierce regard for integrity at the way the city of Tokyo was changing. The city provided the backdrop for his work for much of his creative life and he was one of the most astute observers of the evolution of the city as it moved out from the destruction of the war years into becoming the focus of one of the powerhouse economies of the latter part of the last century.

He received many honours and awards over his long career but perhaps the one that gave him the greatest satisfaction was when he was named a Man of Cultural Distinction by the Japanese State in 1996. He preferred the title he was given to that had he been declared a national treasure.

His devoted wife of many years, Shigeruko, predeceased him in 2006. He is survived by his nephew Takashi Ishimoto.

His funeral will take place in Tokyo on February 13th.

Yasuhiro Ishimoto, photographer, born San Francisco California June 14, 1921, died Tokyo February 6, 2012.

Richard Pare