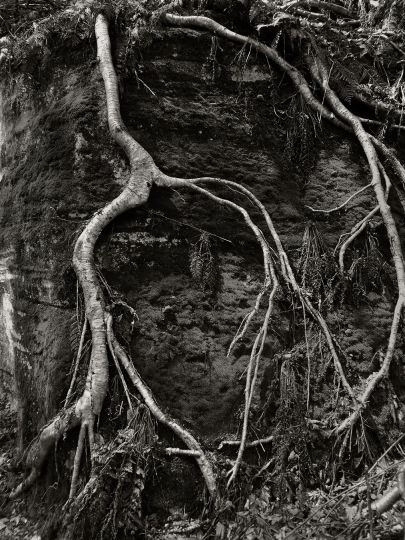

Buffalo News.com has announced the death of Milton Rogovin. In his necrology, the editor of the Buffalo News, Mark Sommer, wrote: Milton Rogovin, the Buffalo social documentary photographer who withstood a government witchhunt to attain an international reputation, died at around 5 a.m. today in his Chatham Avenue home under hospice care, from complications related to a heart attack. Mr. Rogovin, who appeared joyous at a birthday celebration three weeks ago attended by family and friends, was 101.

His work was recognized for revealing the unsung stories and inherent dignity of working-class individuals around the world.

“The rich have their photographers. I photograph the forgotten ones,” Rogovin often said.

Mr. Rogovin turned to photography following the fallout he suffered from being hauled before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1957, including the decline of his optometric business.

Beginning with Mr. Rogovin’s first social documentary series on the East Side, “Storefront Churches — Buffalo,” completed in 1960, photography took him from West Side street corners and Lackawanna steel factories to fields in Chile and coal mines in 10 countries.

While Mr. Rogovin was slow to gain recognition, his photographs today are found in museums around the world, from permanent collections in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles and the Albright-Knox Art Gallery to the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the Museum Folkwang in Essen, Germany.

But Mr. Rogovin maintained he was just as happy to have his artwork displayed inside Buffalo’s Humboldt Station, and on the walls of Columbus Community Health Center — both places with their share of “the forgotten ones.”

“That’s where I wanted my photographs to be shown,” Rogovin told The Buffalo News in 2003. “People come off the trains and see the photographs — friends, neighbors. That’s what I want.”

In 1999, the Library of Congress became the permanent repository of Mr. Rogovin’s negatives, contact sheets and 1,300 prints, the first time since the 1970s the library sought archives of a living documentary photographer.

In 2007, the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Ariz., acquired the master collections of 3,250 photographs and other materials for its archive.

Mr. Rogovin’s poignant studies of laborers have been published in major photography magazines in the United States and around the world, including Germany, Russia, the Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Poland, Hungary, Sweden and Japan.

His dozen books include “Milton Rogovin: The Forgotten Ones,” co-published in 1985 by the Buffalo Fine Arts Academy and the University of Washington Press. It coincided with Albright-Knox’s second exhibition of Mr. Rogovin’s work.

His best known book is “Triptychs: Buffalo’s Lower West Side Revisited,” published in 1994. His wife of 61 years, Anne, assisted and encouraged him, and often propelled him forward when his ambition or spirit lagged. Together they visited a six-block area three times in 10-year intervals from 1972 to 1992 to portray mostly Puerto Ricans and African-Americans living in the formerly Italian neighborhood. Mr. Rogovin was 63 when the project began.

The Rogovins returned to the neighborhood to photograph some of the same people 10 years later, which appeared in a second book, also titled “Forgotten Ones,” in 2003.

Mark Sommer