There are various ways of organising photography archives: alphabetically, thematically, or date of capture. Not so at the Archive of Modern Conflict in Holland Park in London. The 8 million plus images (and there could be many more) are filed according to the date of acquisition, with the archive function- ing almost as a diary, a library of the imagination in the Borgesian sense, or Situationist drifts.

Of all the institutions and archives in the photography sector, the Archive of Modern Conflict is probably the most mysterious. The name of the archive reveals its early focus but it quickly splintered, leading the team down numerous paths of the strange, the overlooked, the forgotten, as well as the mundane. While the archive does possess works by the recognised masters of photography, be it Charles Nègre, Josef Sudek, Eugène Atget, or Robert Frank, the vast portion of the images are by unknown photographers.

The archive isn’t open to the public and few researchers are given access, and only if Timothy Prus feels that something interesting will come out of it. As when Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin were looking for images of catastrophe and violence to illustrate their own version of the King James Bible.

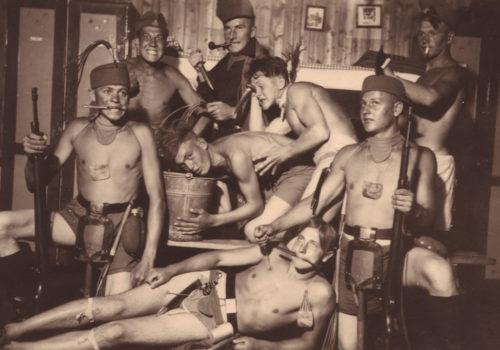

Communication with the world at large is through exhibitions, at institutions and fairs around the world, and the books it publishes. Among the latter are several monographs by Stephen Gill, including Hackney Wick and Archaeology in Reverse. Other titles include The Corinthians – A Kodachrome Slide Show, edited by Prus and Ed Jones, a visual commentary on the letters of St Paul, portraying the prosperity of a post-war United States, where TVs, cars and summer holidays take centre stage, Nein, Onkel: Snapshots From Another Front 1938 – 1945, edited by Prus and Jones, with 347 images of a rarely glimpsed side of life in Nazi Germany, portraying the fun-loving, sexually incongruous and work-shy elements of the German military machine, and The Whale’s Eyelash, a play by Prus in five acts, that unfolds through a series of 19th-century slides, with each slide containing a specific dramatic moment, together telling a story about what hap- pens between the appearance of humankind and its passing away.

There are special editions as well, including Cristina de Middel’s This is What Hatred Did, each copy placed in a unique, original silkscreen printed bag, and Kalev Erickson’s More Cooning with Cooners which comes in a solander box and slipcase with a real racoon coat and tail.

The archive doesn’t limit its acquisitions to photographs. When I arrive at the headquarters in Holland Park, I note other objects, African sculpture, Pacific Ocean clubs and spears, taxidermy, paintings and much else. And yet, what is kept at the headquarters is but the tip of an iceberg, and there are several storage facilities elsewhere.

I started out by asking Prus about his background, his work in British and Abstract art, and his initial interest in photography.

Timothy Prus : I would probably describe it as a background in 20th-century painting more than anything else, but I always liked doing a variety of things. I have been buying photographs since I was a child, as well as books and just strange things I came across. Out of that, photography came to the fore but I always liked to balance it and make connections with other kinds of art and objects because they all interlink in different ways. One of my tutors at university in the 1970s was Professor David Mellor. We shared this fascination of how photography was the perfect medium for finding connections between disparate cultural activities. It would be really good if more people in the photography world were a little bit more integrated and diverse and looked at other kinds of relational objects. It seems to me that photography often becomes an end in itself and it leads to a tunnel vision where there isn’t anything else but photography.

Do you remember the very first photograph you bought?

Timothy Prus : Yes, I do, and very clearly. It was a stereo view. To see something in three dimensions almost made me fall on the floor, because back then, there wasn’t much three-dimensionality in images. That 19th-century stereoscopic material was everywhere, at jumble sales, in junk shops, and you could buy a packet of stereos for less than a few bars of chocolate. Many years later, I had the same shock the first time I saw stereoscopic autochromes.

The Archive of Modern Conflict was founded in 1992. How did it come about?

Timothy Prus : I was a bit fed up with the machinations of the art market. A colleague suggested we put together an aviation-related archive. As soon as we started to collate images, it started to grow exponentially, not just in terms of military related material, because you can’t really separate that from the rest of life and photography. The whole thing just developed an internal logic. While others were chasing photographic masterpieces, and it’s great to do that, there’s a lot to be said for vernacular photography and accumulating images for comparison, research and just finding things that have been lost. More than anything, our aim is to put together an archive of narratives faded from our collective conscious- ness. It has almost become an end in itself, to try and discover more things that have been forgotten, because the erasing of memory is a natural thing for human beings.

The name of the archive would indicate content consisting of conflicts, news that grabbed the headlines but increasingly, the focus seems to be everything else that went on around the headlines?

Timothy Prus : Yes, not only around them, but we look at all different genres, still lives, aerial photography, whatever you can think of, because there are lots of threads between them all. Once you start to draw out those connections, they become ever more pronounced. It becomes like a habit to look at the continuity, morphology, style, subject, time and geography, within what apparently at first sight seemed very different.

I seem to recall that you also have images from estate agents, mundane images, produced to sell houses and flats?

Timothy Prus : Not so many but we do have them. Whenever we find an area where photography has been used for something that is away from the general focus of collecting, we want to collect it. One example is a group of photographs of teeth, taken in the 1960s, that originally came from a New York dentist. We like all the unusual and strange uses of photography. Quite often, images that were produced with- out any aesthetic intent turn out to look fantastic and strange.

Your initial focus was on aviation and conflict but then it snowballed from there.

Timothy Prus : When you’re looking for something, you often find something different that is more interesting, and then you use that as a pathway into whatever that is. We have always tried to set medium-term goals to give us freedom in the search. The pleasure is the process. There’s a sort of temptation just to focus on what you’ve decided to do, but all the best outcomes are byproducts of searching. It’s a kind of mining, fishing, and prospecting. That method- ology gets refined over the years and your instincts are sharpened.

Can you give me an example?

Timothy Prus : Well, we’ve been looking at police and prison photography for the last 30 years. Just yesterday, a wonderful group of 19th-century images turned up, from a Lincolnshire House of Correction. That led to some quick research into exactly what the institution consisted of. I like to engage with local history and within a few hours, with the internet, I could find out so much about what these photos were for and what they meant. Although we look all over the world for things, England and Europe are so rich in good material. Theoretically, we could stay in one place forever and just keep digging for more and more material and information.

You said “we” – are the acquisitions always joint decisions?

Timothy Prus : It depends. There has always been a communal impulse through the whole thing. Someone might go off on a path of their own, and another in completely the opposite direction. I find it interesting how those individual and collective actions can complement each other. It’s great when someone I work with finds some new unbelievable path to explore. If everybody’s focus was the same, it would lead to boring and repetitious kinds of collecting. In addition to the team, we also work with numerous dealers. And dealers are really great because they’ll discover new lines from intent or through happenstance. That can lead to all kinds of unlikely outcomes.

Some of the material you have, like the estate agent images, wouldn’t get a second glance from an auction house specialist. Do the dealers now think, “This is completely random, best call the archive”?

Timothy Prus : Well, it’s never random because although it seems that way, we have our criteria. On the other hand, something might initially sound interesting and then it turns out that it isn’t. It’s not as if everything in this world is interesting. A lot of the time we have to cut out 95% of something we are offered, simply because it is truly useless.

Deciding to buy something is dependent on one’s state of mind at a particular time. I think it’s particularly true when it comes to vernacular photography. Have you ever been offered some- thing, turned it down and then later thought, “I should have bought that!”?

Timothy Prus : There have been many things like that! For example, 25 years ago, I was offered Autochromes that came from the basement of a London hospital but the images of skin diseases were so ghastly. I thought, “Do I really want to have to look at all these?” I decided that it wasn’t the kind of visual self-abuse I wanted to expose myself to. And now of course, I wish I would have had a bit more backbone!

In terms of numbers, how many photographs are there in the collection?

Timothy Prus : It’s very difficult to put an exact number on it. The last time we did a photography census, which was a few years ago, there were about 8 million images. But trust me! 80 or 90%, you wouldn’t want to look at again. It’s just that great images sometimes come in groups. If they’re in an album, you don’t want to lose the context they have been placed in, even though you acquire the album for just a few of the images. Splitting albums is a bit monstrous I think, to sort of peel off images, even if it makes sense from a dealer’s perspective.

The archive has a lot of albums.

Timothy Prus : We do, but they’re not all stored here. Many are in our South London outpost. Some are in other countries so the number of albums is enormous. And it’s not only albums. One thing we’ve worked on since the very beginning is press archives. We have found fantastic things and we are always on the lookout for more. It is, however, getting harder and harder to find truly interesting ones. I really do feel we’re in the last few years where that’s going to be possible. We haven’t found a good pre-Second World War press archive for about four years. We have found sections of archives that have been really good but to find complete archives is so rare now.

Earlier today, your colleague showed some of the boxes with photographs from the Time-Life archive, with prints by Lee Miller, George Rodger and Robert Capa. When and how did you acquire it? Timothy Prus : It was a legendary lost archive! Rumours were flying about and people had been looking for it for about 25 years. We finally found it about 10 years ago. It was a long, long trail that finally led us to the East London suburbs and a loft in a house. I’ve often thought there’s a kind of magic in wishing for some- thing long and hard enough and then eventually, it comes to pass. Although we’ve had the archive for 10 years, we’re still in restoration and research mode on all that material.

What other press archives have you come across?

Timothy Prus : Well, years ago, Europe was the rich source. Subsequently, we have found very good ones in South America, and Africa, some in Asia but not quite as many as I’d like. We are still very active in vernacular Chinese material and we have been for nearly 20 years. The book we’re working on at the moment is about Chinese Yetis, to be published next spring. Our colleague, Ruben Lundgren, who lives in Beijing is working on that. We had a Chinese Yeti session yesterday, which was excellent. What I love about the whole thing is that in the history of the Chinese Yeti, they appropriate photos from America, Bigfoot for instance, and make Chinese versions. I love the way that truth and fiction become allies. We were laughing yesterday when we were looking through Chinese articles about Yetis. One of them was about two soldiers, who claimed to have shot a Yeti in the 1960s but that they had been so hungry that they ate it!

When did the book publishing arm of the archive start?

Timothy Prus : It started in the late ’90s. Then there was a bit of a gap, and we started again about 2005. We have published fewer titles recently but it’s such a pleas- ure. Many of our books aren’t that well known as we haven’t shone as distributors and promoters of our publishing.

Among the many books is Lodz Ghetto Album, written by Thomas Weber. The images were taken by Henryk Ross, after German forces occupying Poland had driven the Jews of Lodz into the Holocaust’s second largest and most hermetically closed ghetto. The ghetto functioned both as a sweatshop and a prison for Jews en route to the death camps of Chelmno and Auschwitz. Ross, a talented photographer, kept a secret diary of life in the ghetto. When the liquidation of the ghetto began, he buried them. He was one of the 5% who survived and dug them up after the war. He released relatively few of the images during his lifetime. He died in 1991 and you acquired his archive. How did you come across it? And why did you decide later on to donate the material to the Art Gallery of Ontario?

Timothy Prus : The Lodz ghetto images came after researching what had happened to this legendary group. The Art Gallery of Ontario was a perfect home for them, as the volume of people interested in it was too much for us to manage. We had already exhibited them about 40 times before we gave them to the AGO.

Are you working on other books?

Timothy Prus : I’m working on one at the moment. It grew out of an exhibition we did at the Contemporary Art Museum in Luxembourg, which is about how plants came from other planets. It’s interesting because on one level it becomes a platform for some lost botanical photographers. We have discovered several great English plant photographers, often women, that have just disappeared from view and they’re so good.

Keeping in mind the unusual nature of the archive, how do you deal with requests from researchers wanting to visit?

Timothy Prus : We haven’t really got the facilities to receive that many. If people write the right letter with a good idea, it’s very difficult to say no, but we can’t help everybody. If we opened up the archive too much, many would come just to have a look out of curiosity. For us, that would be a waste of time, and with all the research we need to do, we’re very short of time.

Has opening some kind of space ever been up for discussion?

Timothy Prus : We have talked about it but it would take away from our research. We do, however, work with lots of institutions and organisations and most of the time that has worked out well, but not invariably. I don’t really like the idea of having a public space with exhibitions. An Indian friend of mine was about to build a museum, but now has an arts organisation that does fantastic pop-up exhibitions, not only of photography, but all kinds of things. The model works so well for him, and he’s able to engage audiences that would never have had access to that kind of material if it was static and in one place.

You have curated numerous exhibitions, including one on clouds?

Timothy Prus : Yes, that was at the Polygon Gallery in Vancouver. And there’s a completely different version of it opening up in Italy soon. It was a great opportunity to exhibit a selection of material we have about cloud photography. Exhibitions are fun to do and you meet interesting people but they also take you away from the basic thing of finding more things for the archive. Another interesting exhibition that was really fun to construct was “A Guide for the Protection of the Public in Peacetime” at the Tate Modern in 2014. It verged on being a collage, an environment, and to a small extent a pacifist manifesto focussing on the futility and surreality of military culture. We also turned it into a book.

I get the impression that you travel a lot to find material.

Timothy Prus : I used to do more than now. At the end of last year, I went to South America and found some great press archive material. I also went to Ethiopia but that was harder. I found a few things but nothing earth-shattering. I will be going back to Africa because we have been lucky there and have acquired some wonderful archives.

Such as?

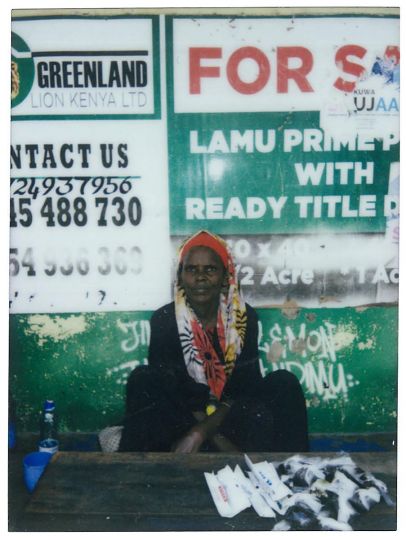

Timothy Prus : We acquired one about ten years ago, an archive from the first colour photo studio in Cameroon, Photo Jeunesse. I travelled around the Cameroons visiting photographers across the country. I was helped by an Oxford professor who has been specialising in the Cameroons for 30 years. The archive has proved to be super popular and we’ll continue to work on getting it out there. The first time we showed it was at Lagos Photo. People loved it. The black and white African studio photography had become too well known in the West. To have a colour version that was also playful in a similar way worked really well.

When you travel, do you manage to hire local agents as well?

Timothy Prus : That has worked really well for us, to engage with both academic institutions and people who just want to work, or simply friends of friends. It has become an integral part of the finding process, and some of those people continue to work with us over decades. It’s always difficult to maintain long-distance relationships but it’s really worthwhile if you can have another set of eyes in Tashkent or Mumbai or wherever.

Do you ever end up in conflict with national or local institutions? That you’re chasing the same material?

Timothy Prus : Not normally, and they’re usually really happy to help. Are they supportive? Not always but we are looking for vernacular material which is not what the museums focus on. If we can genuinely give something back, as well as bring information about another country over here, then it’s a win for everybody. It’s different in Europe, particularly in England. Sometimes we end up in intense competition with local museums or collectors of things that are of local interest. It’s a complicated subject, because quite often that material then stays within the rather insular topography, and it would perhaps be better to reach a larger audience with it.

Despite the exhibitions and the books, most of the archive remains unseen. Is it ever frustrating that you’re doing all that stuff and that the world at large doesn’t know about it, or you’re quite happy?

Timothy Prus : I’m quite happy. In fact, it’s sometimes just easier to have a relatively low profile.

I find it intriguing that the archive is organised in order of acquisition, acting pretty much like a diary.

Timothy Prus : That’s a function of the database. It’s still an ongoing conversation about how it should be organised. Having the numbers running in order of acquisition has some quite good points but there is a great case to be made for organising thematically. We have done that with a couple of subjects, just for the simplicity of comparing like with like.

We have talked about photography but the archive collects in many other areas.

Timothy Prus : Well, there’s the tribal art, folk art and lots of drawings and paintings and manuscripts. The manuscript collection has some very interesting paths in it. Personally, I like all manner of manuals and instruction books, whether it’s cookery, medicine, agriculture, boatbuilding, alchemy, witchcraft or whatever it might be. There are hundreds and hundreds of them. There are also memoirs by people from completely different walks of life, whether they’re bicycle builders or metal workers.

Where do you see the archive being in 100 years?

Timothy Prus : I try not to think of it quite that way. Hopefully, it will continue to be fluid, nimble and opportunistic. I don’t want to set parameters in consideration of what the future options might be. It’s premature to think of a definitive goal to work towards at the moment. In addition, there’s the question of technology and how it will continue to change the nature of archives, what they mean, what they are and how they’re accessed. And who knows? In 100 years, people might simply put on a pair of magic glasses and access images and sounds in archives that way.

Text and interview by Michael Diemar

Article first published in THE CLASSIC Issue 11.

The magazine is available to download at :

https://theclassicphotomag.com/