There is a thought-provoking passage by Walter Benjamin (in Illuminations) where he describes the work of the translator in terms of the shards of a broken object. If the pieces are to fit together, they must ‘follow one another in the smallest detail but need not resemble one another’. Similarly, a translation must follow the original language so as ‘to make both recognisable as the broken parts of a greater language’.

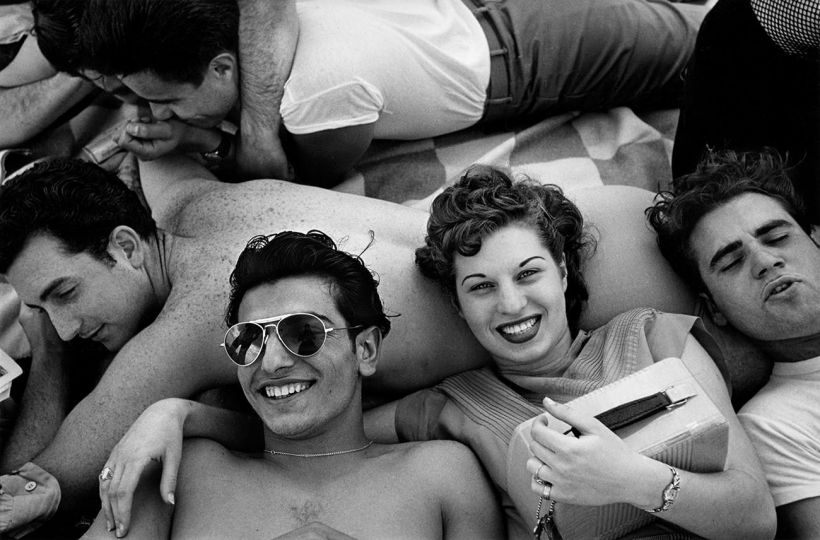

Benjamin’s description serves as a way to approach the photography of Britain in the 1980s as brought together by Tate Britain. The original – the country external to the camera – is not an intact polis, not a united kingdom. It is fragmentary, constituted by bare shards of opposing class interests, and the photography supplements this with it with its own visual fragments. It does not imitate the original but joins together the parts in ways that befit the social and political reality; an uncanny aesthetic act of breaking and putting together: one act opens the space to make the other act possible.

Britain as a fractious state was as nakedly on show in the 1980s as it was in the decade that led to the outbreak of World War II and many of the seventy photographers featured in The 80s Photographing Britain are responding to this. It was, like most decades, a period of change but militancy by the Left and the Right gave it an urgency and depth that makes itself felt in the photography, the publications and the galleries that brought image makers onto a stage more public than ever before. The book, The 80s Photographing Britain, and the exhibition of that name at Tate Britain, looks at what was seen through the lens of activists, how photographers explored new formal and conceptual horizons of meaning and how many of them opposed and battled with cultural norms and traditional genres of British art.

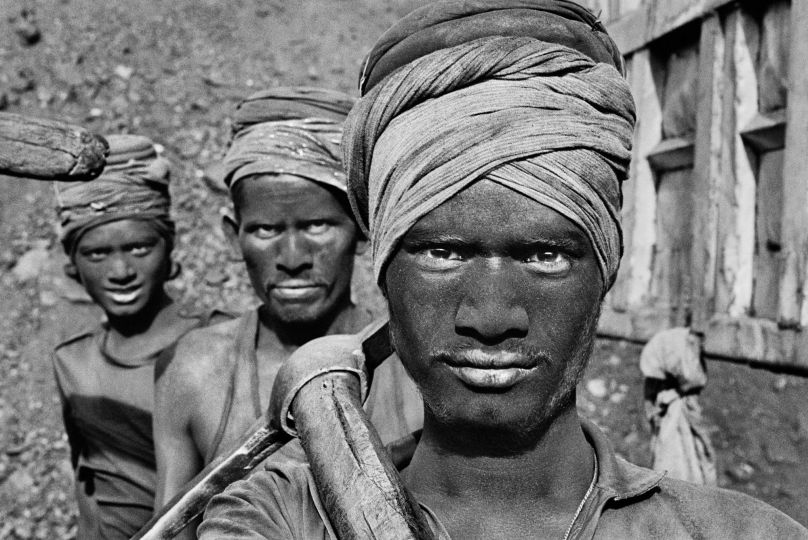

Magazines constituted an important platform for the dissemination of black and white photographs and Geoffrey Batcher’s chapter in the book is devoted to the magazines Camerawork, founded in 1976, and Ten.8 whose thirty-seventh and final issue, ‘Critical Decade’ was dedicated to the legacy of Black British photographers. There are two chapters devoted to this legacy: an interview with Ten.8’s editor and a partial recreation of the catalogue that accompanied the 1986 Reflections of the Black Experience exhibition in London. The impact of feminism is charted by Taous Dahmani while photography collectives form the topic of Noni Stacey’s chapter, with memorable photographs by Tish Murtha, Sirkka-Liisa Kontinen, Marekéta Luskačova. Ken Grant, Chris Killip and others. Political protests in Britain in the 1980s are well represented with images of the epic Miners Strike, gatherings of unlovely racists, antiracist resistance and the poll tax riot.

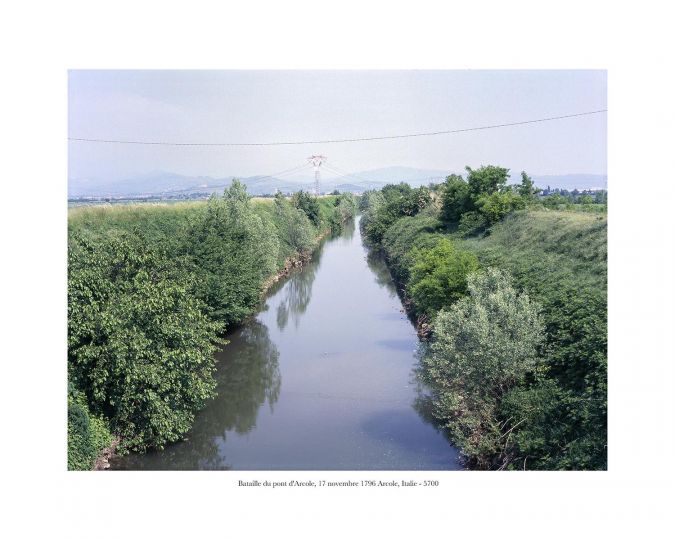

A lot of photographs, text and invaluable documentary references are packed into The 80s Photographing Britain but there is an imbalance when it comes to Northern Ireland .The ‘80s began with a hunger strike by republican prisoners in Northern Ireland and the following year would bring the deaths of 22 men in another hunger strike. It led to a surge in IRA membership and a decade of bloodshed but scant attention is given to photography of the conflict. As with the armed soldier in one of the book’s few images about the Troubles, a Paul Graham colour photograph of a traffic roundabout in Belfast, you have to look closely to see that something was going on there that was just as unsettling – intensely more so when human lives are lost – as events in the rest of the (dis)United Kingdom.

Mainstream reviewers of Tate Britain’s exhibition have tended to be less than enthusiastic. Perhaps, looking for something well-shaped and elegant, they were disappointed by finding fragments of something that was never whole.

The book, The 80s Photographing Britain, is published by Tate Publishing. The exhibition is on at Tate Britain until 5 May 2025.

Sean Sheehan