In West Africa, slavery is a difficult past to face up to, socially and morally. The memory of slavery has not disappeared, but it has been incorporated into various forms of narration that differ from those of the official memory advocated by governments. These are family memories, etched in the daily lives of peoples who have been directly or indirectly confronted with slavery and the European slave trade of Africans.

In the Gulf of Guinea, along the stretch of coast going from the Volta River in Ghana, through Togo to the most western part of Benin, local populations (of Mina and Ewe origin) practice a religious cult that is largely unknown and yet is the living expression of a “historical consciousness” of slavery among local populations: Tchamba voodoo, also called Mami Tchamba or Maman Tchamba.

Tchamba is the name of a spirit considered to be one of the most powerful and dangerous in the region. It is the spirit of the male and female slaves who were deported from the North to the South, in the context of local domestic slavery and, more broadly, of the West African slave trade. In fact, the transoceanic phenomenon of the European slave trade fuelled a local slave trade managed by a number of rich African (and Afro-Brazilian) families on the coast. Following the abolition of the legal slave trade, proclaimed by England in 1817, the growth of the illegal trade was accompanied by a gradual conversion of the economy into the extensive cultivation of palm oil and the development of a new “means of production”: domestic slavery.

The word Tchamba has several meanings: first, it refers to a geographical place, the village of Tchamba, in the central region of Togo, the area from which, according to tradition, most of the slaves were deported to the southern coast. It also refers to the ethnic group of the region, which, along with the Kabre, was one of the main victims of the raids, wars and enslavement that haunted the territory under the pressure of the European powers.

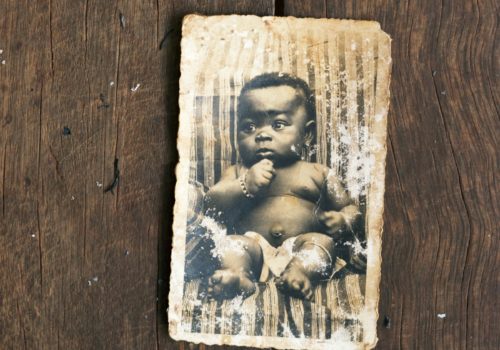

Tchamba gave its name to the voodoo cult and designated the spirit that ruled over this cult: the restless spirit of the person who died in slavery, deprived of the necessary funeral rites and buried outside the village, in a zone (dzogbé) on the edge of the forest associated with the world of the unknown, the irrational and the wild. The spirit returns to be among the descendants of its former master to ask for offerings and ceremonies in its honour, which is the only way to appease its anxiety, and restore order and prosperity within the family. At the time when the domestic slaves were mostly women, married to their master, the followers of Tchamba often bear a double origin as they are descended from both the slaves and their masters.

The ceremony, which varies according to place, family and oracle, is the most elaborate and complex aesthetic event in the lives of the adepts. The Tchamba cult stages the relationship of power between the former master and his slave through two fundamental moments: sacrifice and trance. With the sacrifice, the adepts (Tchambassi) offer the Tchamba spirits the animals and food required to win their favours: “Now that they have returned, we must respect and honour them so that they will make our lives easier. At the time, the slaves ate the remains of the master’s meal. Today, the opposite is what happens. Now that they have become spirits, they are the first to be fed during the sacrifices. We eat after.”

This symbolic inversion of master-slave relations is also effected in the trance. In a mimetic relationship with the enslaved ancestor, the adepts, the descendants of the former masters, eat, talk, dress and behave according to the presumed customs of the family’s slaves. The “wild” and “irrational” North is the imaginary or real place from which slaves are supposed to originate: possessed by the spirit of Tchamba, the adept bends to the spirit’s will, lets himself be guided by the spirit, submits to his orders, becomes the “slave” and, in so doing, restores the lost balance and harmony within the family.

Through Tchamba voodoo, families reactivate the memory of slavery, share it and pass it on to future generations. For the spirit of the person who died in slavery, their place in the family pantheon and the community is acknowledged. Tchamba thus leaves the restless world of the forest and the hills and, at least for the duration of the ceremony, finds peace on the family altar, the meeting place between the visible and invisible world, between past and present, between ancestors and descendants, between former masters and former slaves.

Nicola Lo Calzo

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to all those who appear in this voodoo room and those I was able to photograph but who don’t feature here.

My most sincere gratitude goes to all the individuals, researchers, artists, associations and institutions that have supported me in this project. Thanks in particular to Salissou Mamadou, Alessandra Brivio, Kokou Atchninou, Simon Njami, Natascia Silverio, Elisa Delattre, Céline Coyac, Roger, l’Agence à Paris, the Dominique Fiat Gallery and the Zinsou Foundation.

Tchamba is a phase in the long-term Cham project on the living memories of colonial slavery, resistance to slavery and its abolition.