Fifty years ago, MoMA presented the exhibition “New Japanese Photography.” The T3 Photo Festival Tokyo celebrates this legendary exhibition, which opened up a much broader understanding of post-war Japanese photography.

Yasuhiro Ishimoto (1921–2012), Shomei Tomatsu (1930–2012), Kikuji Kawada (1933–), Masatoshi Naito (1938–), Hiromi Tsuchida (1939–), Masahisa Fukase (1934–2012), Ikko Narahara (1931–2020), Eikoh Hosoe (1933–), Ken Ohara (1942–), Shigeru Tamura (1947–), and Bishin Jumonji (1947–).

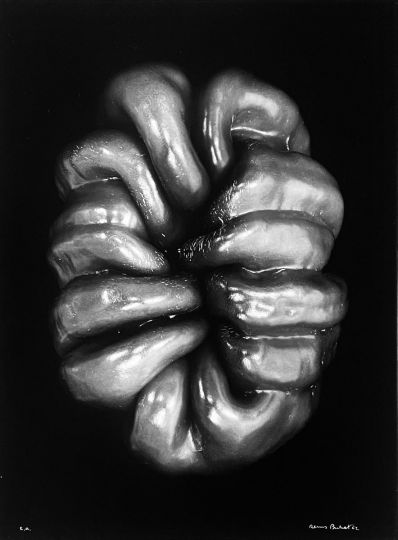

Invited by John Szarkowski, director of the MoMA Photography Department, and Japanese critic Shoji Yamagishi, these fifteen photographers, all men, represented the present state of Japanese photography in 1974. With more than two hundred works exhibited, all created between 1950 and 1973, it showcased the diversity of practices in post-war Japan, supported by a reconstructed economy, exemplified by the first photographic companies flooding the international market. It reflected Daido Moriyama’s grim fascination with the underworld, Ken Domon’s geometric aesthetics, and Shomei Tomatsu’s already mesmerizing blurs.

The exhibition had a significant impact in the United States and Europe. It was not only the first exhibition gathering Japanese photographers outside of their country, but it also inspired numerous Western photographers and bolstered the careers of some, like Daido Moriyama. It also established the importance of photographic publishing in the dissemination of a work, contrasting with Western photographers, who preferred the exhibition format.

In Japan, the exhibition brought about, like a boomerang effect, societal recognition of a photographic art that had previously been neglected or scorned. It raised awareness. Nevertheless, as with any attempt to unify, or any act of synthesis, the MoMA exhibition had some shortcomings, starting with the absence of female artists and the omission of figures that became obvious afterward.

“New Japanese Photography” was also the cornerstone of a series of exhibitions dedicated to prominent figures in Japanese art. In a way, the MoMA exhibition shaped a model for photographic exhibitions, that of a comprehensive review. Subsequently, exhibitions in the United States, Japan, and even France regularly sought to showcase the state of photographic art in Japan and, despite differing aesthetics and approaches, to unite generations of artists under a single banner. In 2008, there was the exhibition “Heavy Light: Recent Photography and Video from Japan” at the ICP; in 2015, “Another Language. Eight Japanese Photographers” at the Rencontres d’Arles; the same year, “Japanese Photography from Postwar to Now” at SFMoMA, and “Provoke” in 2016. The exhibition also led to major photographic acquisition campaigns in museums, notably at MoMA, but also at SFMoMA and the MFA Boston.

As another tribute to this now-historic exhibition, the festival offers a reinterpretation of the works of the fifteen photographers shown in New York, with very large prints, projections, or prints on materials and technologies that were impossible at the time. For instance, Tomatsu’s protest photographs are displayed on porcelain panels, while Bishin Jumonji’s work shifts from photosensitive paper to hemp fabric.

In contrast, the festival also offers a review of Japanese photography from 1974 to 2024, featuring the works of Sayaka Uehara, Misun Gang, Motoyuki Shitamichi, Mayumi Hosokura, Kohei Fukushima, Shingo Kanagawa, and Natsuki Kuroda. A necessarily partial review that follows in the footsteps of the MoMA exhibition with its openness and relevance of artistic choices.

More information