Marginalized and Maligned: Ireland’s Travellers – text by Sean Sheehan

Joseph-Philippe Bévillard has been photographing Irish Travellers for many years and his new book, Mincéirs, opens a window on Ireland’s most marginalized and maligned community. Mincéirs is a term in their language – a sui generis mix of English and Irish known as Shelta – for themselves, once a nomadic people but now largely settled in allocated areas of purpose-built accommodation (anachronistically called halting sites). Irish people who are not Travellers are unfamiliar with the term mincéirs, preferring a number of pejorative words (‘Knackers’ is currently popular); gypsies, one of the appellations still used, has at least the virtue of some romantic connotation.

Adopted and raised in Boston by French-born parents, Bévillard lost permanently his hearing at the age of three. He discovered photography when he was 19 and settled in Ireland in 2000. At that time, it was not uncommon to see Travellers’ caravans parked along the side of roads and, apropos society’s attitude towards Travellers, I recall seeing the entrance to a church’s large parking area fitted with a low-lying bar to prevent the possibility of an unwanted visit from them.

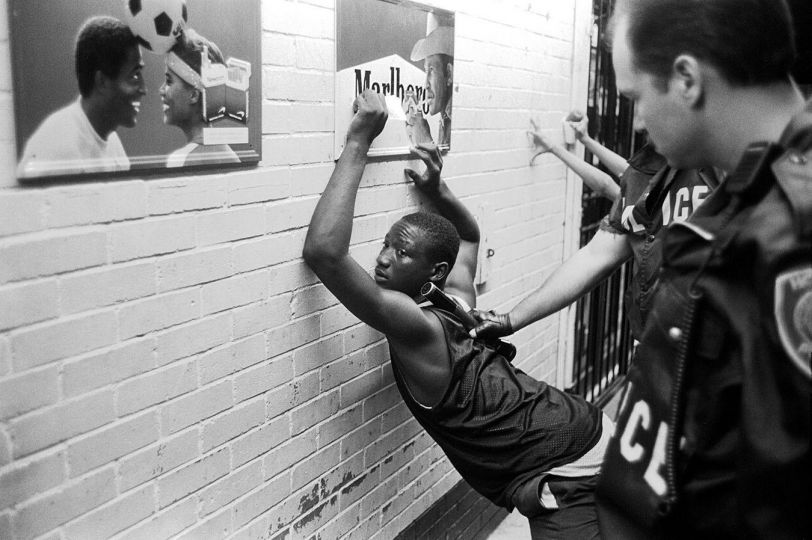

Bévillard has a more Christian approach but his work conveys the continuing sense of their estrangement from mainstream Irish society. He always photographs them within their own milieu, even when they are attending church events like weddings and First Holy Communion ceremonies. Their wariness about engaging with others is understandable and an essay in the book, by Peggy Sue Amison, details their disadvantaged social position when it comes to health, housing and education services.

There are some 90 photographs in Mincéirs but only about half a dozen feature adults in any principal way, easily outdone by the pictures of children.

There is one remarkable photograph that cuts through all of this. It is of a father and daughter at the Ballinasloe Horse Fair, Galway, with the young girl leaning on the man’s shoulder. His pensive countenance is echoed in his own daughter’s contemplative expression and, taken together, their faces hint at a ruefulness that is disarming. The presence of children in the book is very strong. They play and pose with a range of attitudes from precocious nonchalance and savoir faire to resignation and melancholy.

Bright, saturated colours in the pictures are counterpoised by the drabness of the environment outside Travellers’ homes: vacant lots, waste ground, railings and fences. There is refreshing honesty to the photographs: humanist in the best sense of the word, they depict individuals in their own right and are not shown to illustrate a sociological observation or a journalistic angle.

Sean Sheehan

Mincéirs, by Joseph-Philippe Bévillard, is published by Skeleton Key Press.