Nine years after his first trip to China, Marc Riboud returned to China, the China of 1965, on the eve of a devastating upheaval which will be officially called “Ten Years of Chaos”. For four months he toured China from South to North from East to West, along with French reporter of Polish descent KS Karol. By train, by car and even by plane and by foot, they travelled more than 22,000 kilometers across twelve of the eighteen provinces of China. If the countryside and rice fields remained tranquil, idyllic, except for those, students and intellectuals sent to work in rags with their bare hands in earthwork sites captured by surprise by Marc, in the cities there was already premises of the sounds and fury to come. Like these students marching in step with wooden rifles, these young militiamen marching and training with real guns, mass protests in Tiananmen Square or in stadiums against imperialism. Upon their return KS Karol published “The other Communism,” and Marc Riboud “The Three Banners of China,” both books came out in 1966 when the Great Cultural Revolution reached its climax. The “Three Red Banners” (San Mian Hongqi) refer to the ideological slogans of the second Five-Year Plan launched in 1958, calling for the faster development of a strong and prosperous socialist state around the “Great Leap Forward”, the “General Line for Socialist Construction” and the “People’s Communes”. Curiously the title used by Marc Riboud refers to political campaigns that were not yet active during his trip in 1957 and already phasing out upon his return in 1965 following “Three Years of Natural Disasters” resulting from the Great Leap.

In the absence of Mark’s travelogue one can only attempt to reconstruct his itinerary. We assume that he began his journey as in 1957 by Canton via Hong Kong, probably towards the end of the Chinese New Year (which begins February 2, 1965, year of the Wood Snake), from there he took a 48-hour train ride to reach Beijing. It was only after visiting Beijing and Shanghai that Marc went touring in the hinterland of China.

Starting with the Southern provinces of Yunnan and Guangxi, where he obtained an unexpected permission to photograph farmers at work in the People’s Communes that were at that time rarely visited by foreigners. From Nanning, Marc made a pilgrimage to the birthplace of Mao, in Shaoshan. A small plane then took him to Yan’an, Mao’s refuge after the Long March. At each step he photographed Mao’s childhood bedroom, Mao’s bed with the mosquito net in the cave dwelling in Yan’an, with similar Spartan setting and dim natural light, as if he had wanted to penetrate the mystery of the origin of the Dong Fang Hong (East Red Sun). “To see the Chinese industry in its most impressive achievements”, Marc wrote in The Three Banners, “we roamed the North-East, from the former Manchuria to Harbin, near Siberia. Finally in Russian-made jeeps, our guide carted us around for hundreds of kilometers across the vast plateau of Inner Mongolia, to spend a few days living with the nomads”. As a witness to the tensions in this part of the world in the 1960s, Marc Riboud immortalized in another iconic photograph the figures of Mao and Ho Chi Minh appearing side by side on placards brandished by cadres of the Central Academy of Fine Arts in one of the many almost daily anti-American demonstrations and mass rally. What Mark was not aware of was that in the month of May 1965 Ho Chi Minh flew in on a secret mission to the birthplace of Mao to seek military help to face off the growing threat posed by US armed forces in Vietnam.

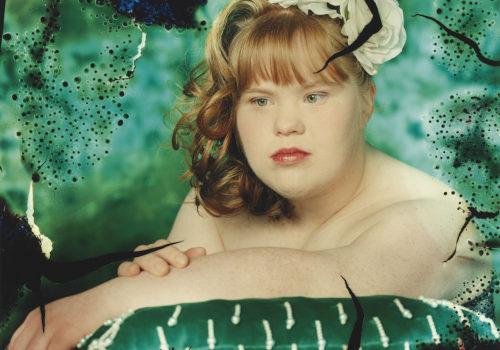

“In Beijing and Shanghai, we went around by ourselves, without interpreter, day and night, on foot, by taxi, by bus …,” says Mark, “We wandered through the narrow streets of old Beijing neighborhoods and entered at random in restaurants, small shops, cinemas, parks and forlorn temples, attracting the attention of groups of children particularly amused by the length of our nose.” Actually, by that time, Barbara Chase, Marc Riboud’s first wife, had joined him in Beijing, Barbara is an American artist, sculptor and writer. These children amused by Marc’s long nose were far more fascinated by the sight of a tall and imposing foreign lady, for Barbara Chase was not only the first American woman to visit Communist China in 1965, she was also the first “African-American woman” in China. Such a sight it was! Marc Riboud had wanted to take Barbara to visit the sculpture class at Beijing’s Institute of Fine Arts where he had photographed nine years ago the amazing scenes of students working in full concentration with young girls posing nude . But what was exceptionally made possible during the 1957 Hundred Flowers campaign was no longer allowed in 1965, the year of bitter political infighting at the highest level of the state, and of alarming tensions in the South-East Asian peninsula with the outbreak of the Vietnam War and the crisis in the Taiwan Strait.

As Marc and Barbara wandered into the street of antique stores, let’s point out that the name LIULICHANG dates back to the Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368), it was originally a factory of glazed tile, the Court of Yuan had built on this site four imperial kilns to produce colored glazed tiles for the roofs of the palace, leaving the name “Factory of Glazed Tile” that still lasts today.

Inside a curios shop, Barbara wanted to buy an antique seal and began to negotiate the price. Marc turned to the shop windows with six openings. He saw the children pretending to pass by but actually trying to take a peep at what was going on inside the shop. Marc pointed his Leica and instinctively fired a shot, though slightly slanted, that was how one of Mark’s most iconic photographs was born.

Indeed in one photograph there are six photographs.

William Fox Talbot (one of the inventors of photography) wrote on a piece of paper in 1839 that he wanted “to photograph a kaleidoscope”, from Greek kalos meaning “beautiful,” eidos “image” and skopein “to watch”. In this image of Marc Riboud that invites us to watch, there is a subtle interaction as we look from the interior of the store at the exterior, when from outside the store children are trying to peer inside. There is a confrontation, a contrast, between light and dark (chiaroscuro), black and white, between what is enclosed and what is open, again, this is something very “Marc Riboud”: like in his picture of the Eiffel Tower Painter the contrast between human presence and metallic structure, all contradictions perfectly wedged in a balanced geometry.

And if one attempts to dissect this “Image of the Image” into separate pieces we can obtain six pictures each framed by the rounded edges of the windows that offer a wealth of incredible information.

We can study the architecture of these traditional stone houses of the suburb of Beijing, with their cornice and decorative frieze, and other stores with multiple windows. The black lacquer sign with gold characters “RONG XING ZHAI”, was a famous hundred-year old jewelry store held by Muslim Hui merchants Hui who specialized in jade, someone wrote on a rice paper “here we buy jades, diamonds, pearls, precious stones, carpets, embroideries, porcelain. Business as usual.” The irony was not lost to Marc Riboud who wrote in subsequent caption that during the Cultural Revolution this Liulichang Street was turned into collecting points where Beijing citizens were requested to hand in all their most precious treasures, their “Jades, diamonds, pearls and ceramics.”

Overall, here we are dealing with not only an iconic picture but with a true polyptych altarpiece with six panes! The wonder with this snapshot of Marc Riboud lies in that not only our vision has been multiplied by six, from the interior to the exterior, but more like the other side of the mirror, we have also three other stores across the street with one having virtually identical windows, which give us the possible and probable composition of the front side of store where Marc Riboud took the picture.

Finally, to complete this tribute to Marc Riboud, we have discovered a never-published before image that delivers the context and the perspective of this Liulichang Street. The photo shows dilapidated storefronts lining up on one side, in the middle of the road a “chauffeur” riding a tricycle-taxi, has he just picked up the son of a rich family from school? From inside the funny looking wooden cage, the kid is peering out at Marc. Outside one of the shops on the left, a rice paper advertising says “Zongzi”, that glutinous stuffed rice wrapped in bamboo leaves traditionally eaten during the Dragon Boat festival (Duan Wu), which gives us the date of this picture, which on Marc Riboud’s contact sheet, is four frames before the famous “Windows”. That is to say this picture was taken in May 1965, exactly fifty years to this day.

Marc Riboud is also exhibited at Polka gallery through August 1st. The exhibition titled “L’un pour l’autre Le goût de l’échange” is curated by Michel Frizot, historian of photography (CNRS).

EXHIBITION

Marc Riboud’s “Windows of Liulichang” 1965-2015

From Paril 18th to August 31st, 2015

Beaugeste Shanghai

210 Taikang road Tianzifang Building 5 space

519-520 – Shanghai 200025

China

Tel +86-21-6466-9012

http://www.beaugestedesign.com

http://www.beaugeste-gallery.com

ALSO

L’un pour l’autre Le goût de l’échange

Marc Riboud

From May 30th to August 1st, 015

Galerie Polka

12, rue Saint-Gilles

75003 Paris

France

T +33 1 76 21 41 30

[email protected]

http://www.polkagalerie.com