The Human Body as a Landscape

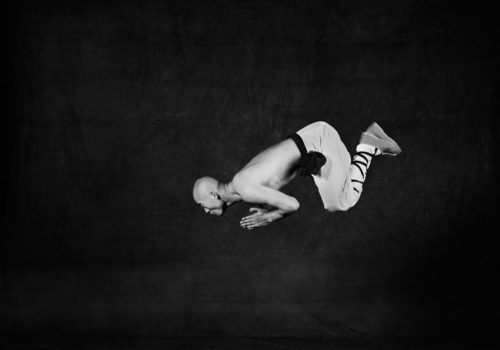

Five or six years ago, I discovered thanks to Christian Caujolle a few prints of Shaolin Monks by Isabel Muñoz. I remember the sudden inexplicable feeling of euphoria at the sight of these monks dancing and flying. To a fan of “wuxia” novels (1) that I was, it was like a dream come true. Shortly after, in a cinema watching Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger and Hidden Dragon, I was seized by the same emotion from the first minutes of the film, the wonders of technical prowess have made it possible to reproduce on the silver screen what was only wild imagination in our mental screen while reading wuxia novels; now these characters are actually evolving in total weightlessness on walls and roofs and on tops of bamboo groves. But unlike cinema, Isabel’s photography, in its splendid sobriety, made no use of faking or special effect, and this renders it all the more precious and fascinating to me. I was especially fascinated by this direct confrontation of photographic realism with almost dreamlike scenes, magical, in the magician sense for the uninitiated.

In 1998, Isabel Muñoz came to China to photograph the acrobats of a circus school with the help of the Spanish Embassy in Beijing. A journalist had told her about the Shaolin monks, she became curious of their practice of ancient martial arts, and expressed her desire to meet them. An official in charge of External Relations of Henan Province then organized a trip to the foot of the pantheon of martial arts, the Shaolin Temple of Songshan (2). These Shaolin monks at the time thanks to kung fu movies from Hong Kong were already known around the world. Their monastery was surrounded by a hundred martial arts schools in which students training for years just for a final entrance examination, either to the Shaolin Monastery for the best among them, either into the army or police for the others. Fanatics and curious visitors flocked from afar, they came knocking on the monastery’s door, to see and to learn their secrets (3). So there was a moment of skepticism and mutual observation before giving way to total trust between the photographer and her models.

How Isabel, a woman from Europe, not speaking the local language, was able to convince the monk-warriors to pose for her, to do the movements she wanted, they who had until now become so accustomed to deploying their routine demonstration for television and reporters? Isabel began by showing them her previous works, on dance (Tango, Flamenco), and on the Turkish wrestlers. When finally the monks agreed to reveal what each of them did best, it was time to identify the most choreographic movements in their boxing or fencing. For the décor Isabel proceeded to “tracking the energy of the place” and chose to move away from architectural stereotypes, instead she focused practically on the ancient walls and the dirt floor. Here was an extraordinary opportunity to continue her study of the body, especially the body in motion, and the energy that emerges which she always identifies with a spiritual dimension. “Too much architecture kills mysticism,” she said. This remarkable minimalism is obtained by separating, obliterating the “Shaolin” context in spite of the tempting beauty of ancient stone. She also had to familiarize the monks with the presence of the photographic equipment they had never seen before: flash, reflector, umbrella, tripod, and three cameras: Hasselblad (6×6), Leica (24×36), and Mamiya (6×7). It looked as if she had carried to the heights of Songshan Mountains her photo studio, for an intimate sitting between the photographer and her subjects.

So began the most difficult part, how to overcome the language barrier to explain the desired shot? After an entire morning spent trying to make the monks jump, dejection came. “I was so desperate; all they did were tiny little jumps!” As the monks left for lunch, Isabel did a trial with her assistant David, a former basketball player who had put on weight, “can you leap as if you fly in the air?” And miracle! The Polaroid got the right shot! And that Polaroid print had piqued the monks’ pride, they were now motivated to prove their real talent. They also understood the causal relationship between their moves and what would be stored inside Isabel’s cameras. From this magical complicity came extraordinary images, portraits of stunning classicism. The Photo Studio now reduced to a confined space, with the gray walls of the monastery set as a backdrop, forming an enclosure where Isabel could fully engage in a body to body confrontation with the warrior-monks, given the martial dimension of the session, the shooting felt at times like a corrida between the bull and the toreador. The Shaolin monks had no other way out but to transcend themselves.

Isabel knew from her accumulated experiences of dance photography, how to capture the pulsating energy that was gushing through the feet, the fist, and the fingertips. In the symbolism of the human body, according to the Taoists, Man, standing between Heaven and Earth, is a landscape, in which an inner eye would see the mountains and waters and energies circulating in-between. In the Judeo-Christian concept the human body is a tree (4), which would also join the Indian thought, which views the body as an inverted tree. Thus in the practice of yoga; one of the fundamental origins of the Shaolin martial arts, the headstand posture (5) represents a tree right-side up. By immobilizing them on the ground, in the air, or in the midst of a fall, or in the inverted posture, in these moments of pause, fixed concentration, and suspended breathing, Isabel has erased all martial semantics retaining only the beauty of the choreography.

Isabel Muñoz’s practice is not a photography of movement, but a photography of landscape. She lets us see in these monks: trees, mountains, sculptures, a still life that invites meditation. And in the contemplative stillness we are touched by an energy that is directed towards one single goal: deliverance.

Jean Loh — June 2012

1- Wu from Wushu (Kung Fu) = martial arts, Xia = hero: the genre of initiation novel with complicated intrigues involving heroes and heroines with phenomenal powers, through fantastic adventures interspersed with scenes of martial arts fighting, with bare-fist or with sword, saber, and a variety of traditional and fantasy weapons, in which the Shaolin Temple is systematically present (for comparison we could think of French and Spanish swashbuckling novels of 19th century, roman de cape et d’épée or comedia de capa y espada)

2 – Isabel Muñoz received the 2nd Prize of World Press Photo category Portraits Stories in 2000. Quoting the WPP archives: “At the Shaolin temple men practice a particular form of wushu, war art. The 18 basic positions of what some call Shaolin Kung Fu are inspired by the movement and agility of animals. According to legend, over 1500 years ago the Buddhist monk Bodhidharma introduced Indian principles of meditation and yogic calisthenics to the Shaolin monks’ own tradition, to help them endure the physical demands of long period of meditation. Over the centuries, the men of the Shaolin temple added skills from different martial arts to Bodhidharma’s original system, and became known of warrior-monks.”

3 – Those were the days when their touring demonstration was the highlight of the official cultural exchange programs. The monks that Isabel photographed had still some sort of authenticity if not to say “purity”.

4 – Symbolism of the Human Body, Annick de Souzenelle, published by Albin Michel 1991.

5 – Inverted posture or headstand, Sirsasana (Sirsa in Sanskrit: the head). “In the ancient literature, Sirsasana was called the king of all postures (asana). The reasons are not hard to find. When we are born, the head usually comes first, then come the limbs. The skull contains the brain that controls the nervous system and the organs of the senses. The brain is the seat of intelligence, knowledge, discernment, wisdom and energy. It is the seat of Brahman, the soul. A country cannot prosper without a capable king or constitutional power to guide it, so the human body cannot develop without a healthy brain.” B.K.S. Iyengar. Yoga Dipika Light on Yoga, published by Buchet / Chastel French edition of 1978.

Shaolin Dancing Warriors – Isabel Muñoz

From June 16th to September 30th 2012

Beaugeste-photo Gallery

Lane 210 taikang road, building 5, studio 519

Shanghai 200025 – China