« The darkroom is an integral part of photography. When I take photos late into the night, which I then develop in the darkroom until the small hours of the morning, bathing the prints in the tray, then removing them to discover the images as they first take form, it’s like giving birth to a child. »

– Seydou Keïta

Seydou Keïta, an innovator who became a school

When one poses for a portrait, one generally tries to show oneself in the best light. Traditionally, this means wearing one’s best clothes, accessorizing, and striking a flattering pose in a setting that enhances it. Seydou Keïta learned these conventions while working with the Bamako-based French photographer Pierre Garnier, but when he opened his own studio in 1948, he innovated by creating types of portraits better adapted to the desires of his Mali clientele. In particular, he used his own props and decorations, invented new poses, and above all introduced ornate clothing and backdrops. […]

His methods attracted new clientele and, most of all, helped to influence photographers in Mali and elsewhere in Africa, and even certain European and American artists. […]

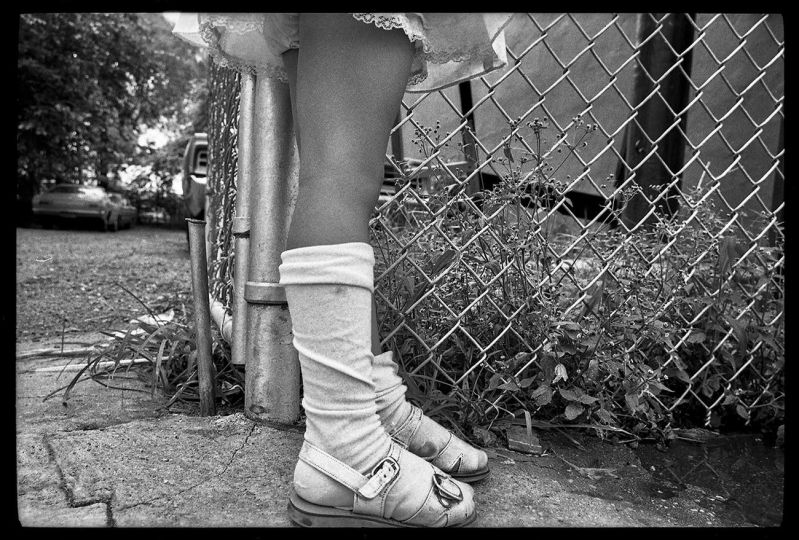

His props allowed clients to show they were up on the latest fashion trends, display wealth they might not have had, and sometimes pretend they were someone they were not.

Traditionally, the most sought-after props were cars and motorcycles, symbols of social advancement, and they often featured in Keïta’s portraits. Some customers would arrive in their own car or moped but, as a general rule, the photographer would lend his Vespa. […]

The pose adopted by the model was another critical parameter. Thus Keïta adapted or updated the odalisque-style pose popularized by nineteenth-century orientalism, generally in the form of barely clothed woman, reclining in a harem or a boudoir decorated with rich designs. At the time, European artists approached North Africa and the Middle East from the perspective of Islamic exoticism. Given the age-old presence of Islam in Mali, where the religion appeared as early as the eleventh century (today, nearly 90 percent of the population are Muslim), French colonists would send postcards back to Europe which featured women — the “exotic natives” — posing as odalisques. Keïta, who was certainly familiar with those images, adopted the pose with the key difference that it was up to the client to decide. Women could use it as a way of courting their suitor or showing off their capacity to attract men. […]

Keïta felt it was important to place the subject against a backdrop. He said that “one cannot put a client before a blank wall; that’s disrespectful.” […]

– Dan Leers

Seydou Keïta

From March 31st to July 11th, 2016

Grand Palais

75008 Paris

France

http://grandpalais.fr

http://www.seydoukeitaphotographer.com

Seydou Keïta

Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux – Grand Palais, Paris 2016

22×24 cm, 224 pages

248 illustrations

35 €Download App of exhibition here :

https://www.mobileaction.co