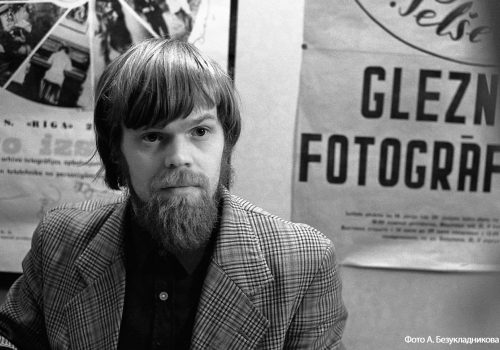

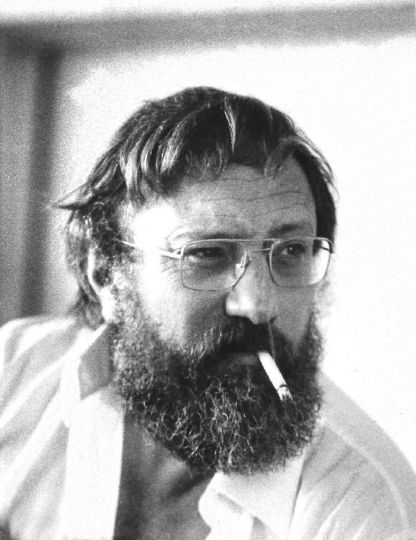

Although I knew Sergei Chilikov had been seriously ill for a long time, I couldn’t believe he had passed away. I still don’t believe it. His youngest son was named Dar [Gift], and Sergei Chilikov, crazy and clever, wonderful and occasionally unbearable, was a Gift himself. His gift has remained with us. Our museum collection includes more than 200 of Sergei’s photographs, and our library has his three remarkable books on philosophy. Before his death he managed to finish another book. I am sure it’s superb, and I hope we will be able to publish it.

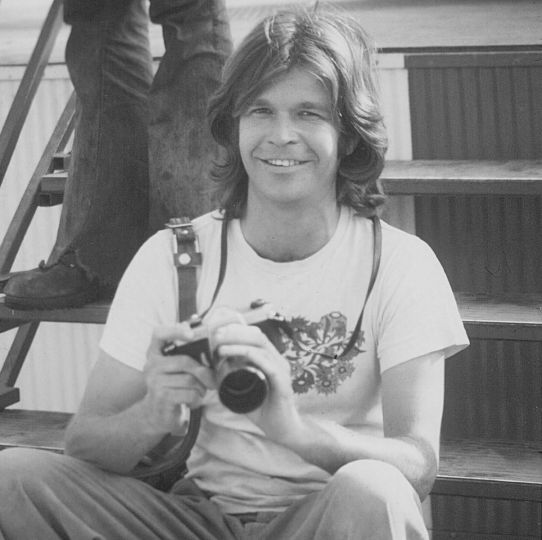

It was strange the way I met him, in 2000. He came to the museum looking dishevelled and very tipsy, and the office, as always, had a lot of work to do. There was a kitchen in the old building of the Moscow House of Photography, and everyone who came to the museum went there to drink tea while I sorted things out. That evening Garik Pinkhasov, an old friend and the only Russian photographer at the Magnum agency, also happened to be in the kitchen. When I got to see my guests at well past midnight Chilikov had left, so Garik and I went to my house and talked until five in the morning. As the sun was rising he laid some small, quarter-A4 contact prints on the table. He said they were interesting, and I was stunned. I asked where he got these masterpieces. They turned out to be from Chilikov, the two of them had spent the whole evening talking. In the morning I tried to find Sergei and discovered him without his passport and camera, but with a backpack of brilliant photographs. His passport was restored and another camera provided, then we purchased his extraordinary images for the museum and a few months later held the exhibition that was awarded the Silver Wreath. It seemed to me, that silver wreath always remained on Chilikov’s head. He radiated light and an amazing energy that transformed everyone on whom those rays shone. In the 1980s the germinal point in the development of photography shifted to Yoshkar-Ola, where he taught philosophy at the university and organised the first Russian photo festival.

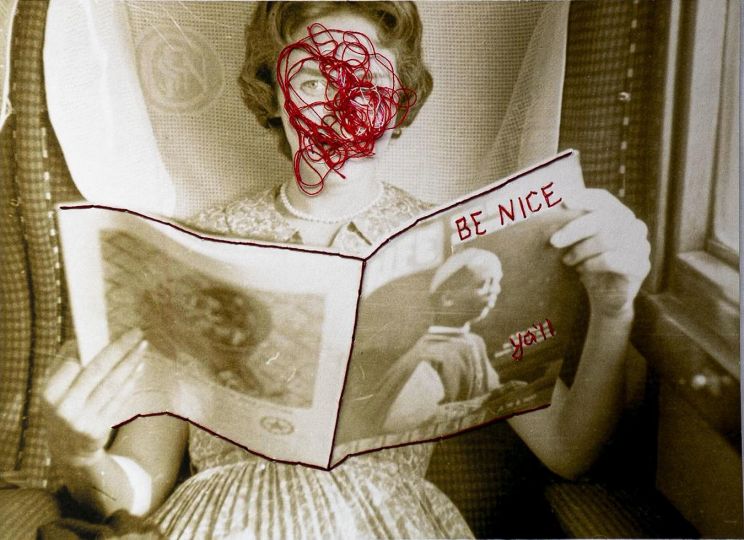

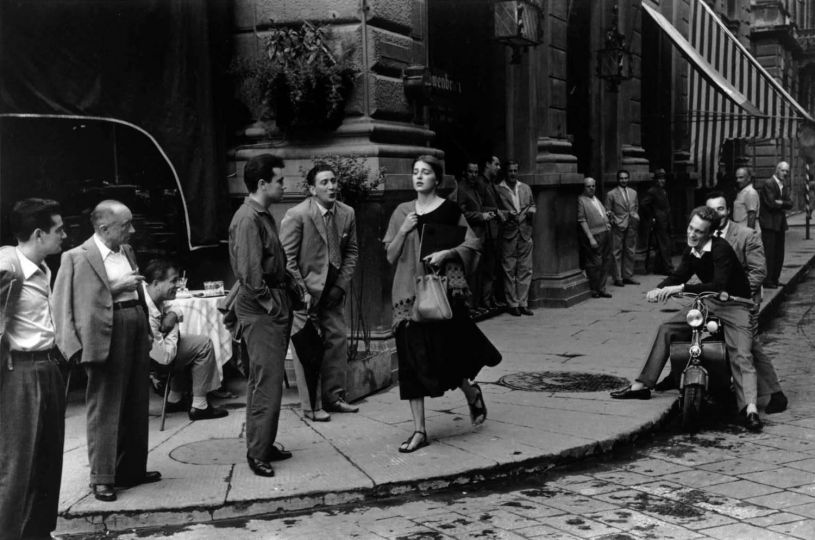

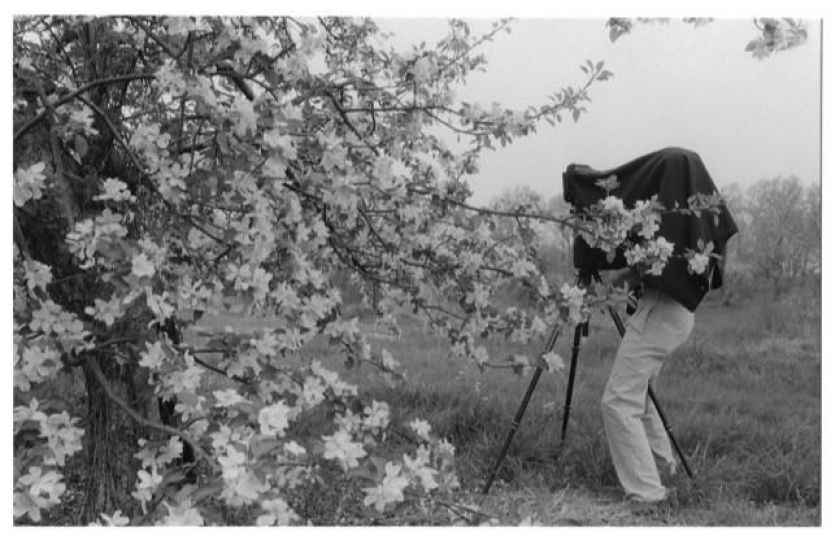

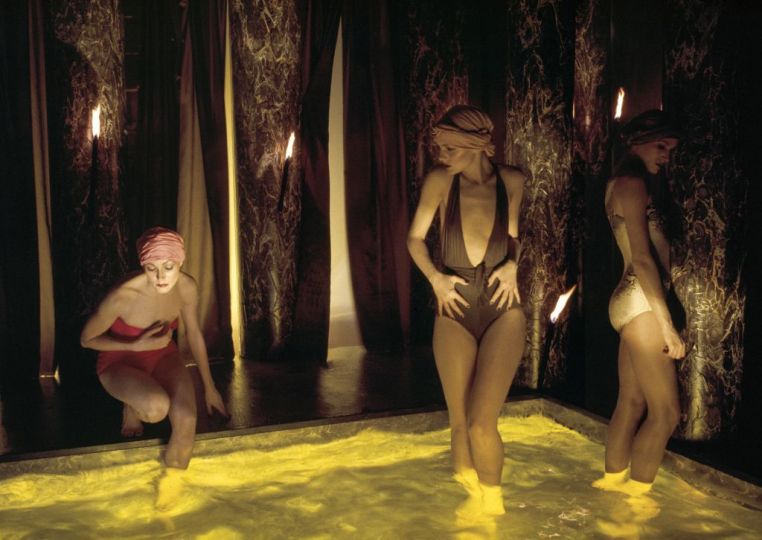

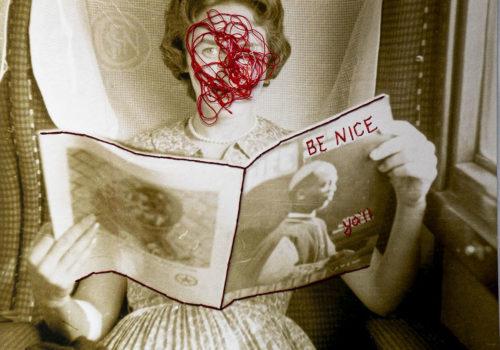

Chilikov not only expressed time when he began working with photography in 1976 during the Brezhnev stagnation, he was ahead of it. He invented his own method, ‘photo provocation’. His camera directed at an individual became an emanation of the attention this person was effectively deprived of in their monotonous everyday life, severely restricted by the framework of the absurd Soviet system. His photo performances expressed the collective unconscious of Homo Sovieticus, yet also provoked participants to the self-expression that is ‘natural’ in a human being, although well concealed behind artificial rules and norms. As a result there emerged a striking tension between the static of ‘unnatural’ poses and the dynamics of a person’s internal state. In his works Sergei Chilikov articulated the immanent gap between the dream and the surrounding reality. Sergei Chilikov’s images are the visualisation of a Chekhovian worldview in which the absurd, and the torment of the free spirit are realised within the closed contexts of banal everyday existence.

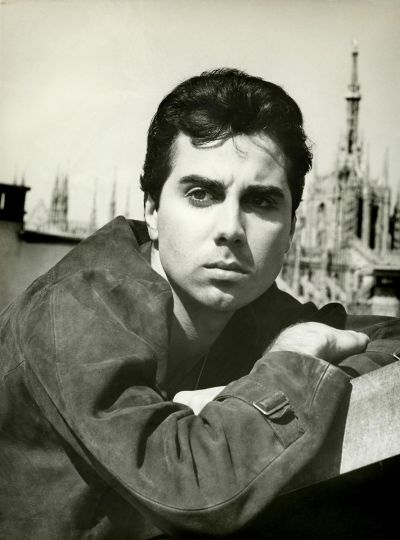

When we exhibited his work at the Rencontres Internationales de la Photographie d’Arles in 2002, it created a furore. In worn-out boots with flapping soles he walked proudly round this beautiful little town that becomes the centre of world photography for one week every year, repeating: ‘I’m number five’ — the number of his exhibition on a topographical map of the photo festival. We bought him new trainers, and wearing these he attended the most important party in Arles, in the house where Jacques Henri Lartigue, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Martine Franck, Sarah Moon and other great photographers often stayed and lived for a long time. Sergei, who did not speak foreign languages, found a way to make contact. In his new trainers and full formal attire he jumped into the swimming pool, drawing everyone’s attention. Henri Cartier-Bresson spoke with Chilikov more than anyone else that hot noontime, and Chilikov took a superb photograph of him for the cover of his new book. Milan applauded him when we brought his exhibition to the Milan Month of Photography. In Milan Chilikov had a delightful translator, an art historian from an aristocratic family. At some point we went to the station, part of which featured exhibitions of contemporary art. I went to view the exhibits while Chilikov, his translator and her female friends stayed by the fountain. A surreal scene greeted me when I returned some twenty minutes later — his translator, her friends and a few random passers-by were standing in the middle of the fountain, topless and exquisitely posed in the Chilikov style. When I asked what Chilikov had done to these Italians he spread his hands with a happy smile. In the morning, now with a larger company, Chilikov photographed his new Italian friends on Milan’s main squares. That evening he staged a bull fight with Koudelka. They were the stars of this international festival and proved who had the most press following. Sergei was adored everywhere he went, it was impossible not to love him. ‘Le Monde’ commissioned reportages from him and he was a favourite of the French and world press but, alas, Chilikov was already unable to attend his own Photo London exhibition, which also became a focus of attention.

He began his photo performances in a far-off Russian province where the realities were only a backdrop; what was real and most important in the people he magically portrayed as he performed a shamanic dance with his camera turned out to be universal and understandable without translation.

It seemed to many that Chilikov was strange and half-insane, but only the holy fool can tell the truth. This crazy photographer told the truth about every one of us with words, in his books, and in his photographs. Moreover; he was endlessly kind, he truly loved life and people.

Olga Sviblova