What does photography mean nowadays? Where is the photographic in today’s photography? How has the image, its distribution, its ease of access affected the medium? The Museum of Contemporary Art in Gand (S.M.A.K.), under the direction of curators Martin Germann, Tanja Boon and Steven Humblet, asked itself questions like these.The Flemish museum takes the opposite point of view of other exhibitions: photography should be dead, photography should be out-dated, beyond photography! In two exhibitions, one until January 7th, the second in 2019, the S.M.A.K.is offering a restitution of the “photographic condition”.This goes beyond the medium and the technique, it adapts to technological change. Well thought out, showing Belgian as well as international artists, the exhibition makes sense.

The first exhibition at S.M.A.K. responds to these questions in two ways. The museum takes as its hypothesis that photography is the one and only common artistic language in our globalised world. If that is accepted then a photographic work remains a word used to see the world, and photographic art a visual language shared by everybody: photographers, and viewers.This first exhibition is structured in three sections. The first part shows brilliantly what photography induces. Namely, what the viewer understands from a photograph.

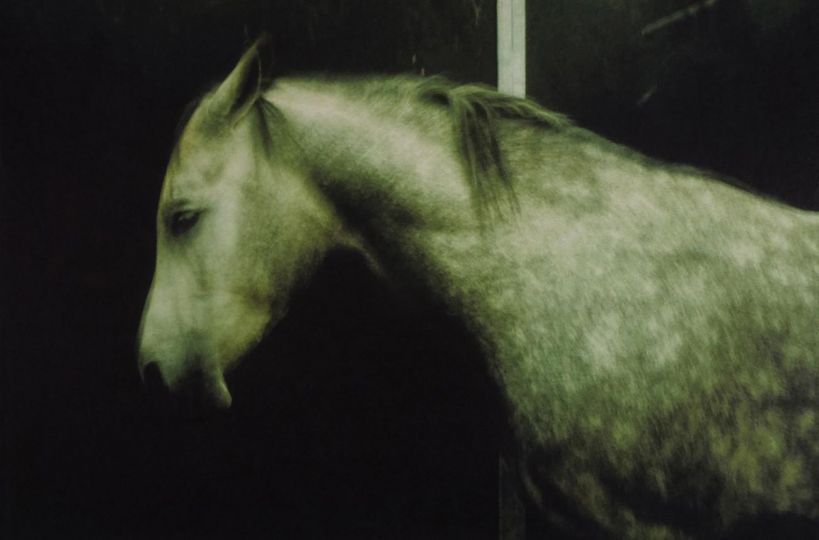

From the prints by the Belgian photographer Marc Trivier, an apparent fragility bursts out from a trunk’s gnarled bark. Going from one print to another, from the portrait of a calf to one of a grizzled old man, the two are connected by an invisible thread. Linked together the prints acquire a fragile sensuality. Deliberately including the negative’s border recalls the impression, the presence of the photographic medium. Seeing it gives rise to an unexplainable emotion. In the face of the most ordinary, of a rough trunk like that of a man laid bare, exhausted by time, there comes a brief and evanescent certainty of grasping something more profound.

In the same way, the prints by Malick Sidibé, Patrick Faigenbaum, Doug Richard and Tina Barney have this function not of representation but restitution of reality. Through the image we are given the understanding of social reality, of slices of life, of social strata. Patrick Faigenbaum and Tina Barney show the distance between the affluence of the well-off and their social conventions, between their standards and the relaxation of bodies in situations of abandonment. With his famous series Périphériques (2005-2008), the French photographer Mohamed Bourouissa questions our preconceived ideas about the French suburb, its boredom and its concrete beauty. Does the viewer share what he sees? How does he relate to what he sees? How does he interpret the images that blur the media representations and give him a different understanding?

“When the facades fall away” the curator Tanja Boon found this expression to sum up the first section of this first part. With photography, the facades break up, the masks slip away, realities touch, rise up, get carried off.

The second part questions the photographic act and analyses how certain artistic choices influence the understanding of the image. Behind the appearance of the image, the intention. Jochen Lempert’s barely sketched, delicate photography is certainly the best example of the second part. A biologist, Jochen Lempert diverted the camera and its scientific use to show the disguises possible in photography. A cat that creeps between light strips, an insect camouflaged in a leaf’s grooves.It’s the art of the detail faced by the visitor who goes past too quickly. Lempert plays with this technique’s possibilities and reveals poetically nature’s wonders. By contrast, the American photographer Zoe Leonard confronts the impossible capture of light. The sun taken face on without a filter only reveals a brilliant stain, that burns the rest of the image. The intention here is an impossible game with light, a competition lost in advance.

The French photographer Jean-Luc Mylayne takes Henri Cartier-Bresson’s decisive moment to the point of absurdity. The artist is a friend of birds. He is capable of staying in one place for three or four months waiting for one of his companions to take-off. In spring, some of them come back to see him and to give him the winter’s news, and the oldest come to die beneath his window. Certainly, his photography waits for the moment of take-off, the presence of one nestlings on a leaf, a conversation with the artist, but the subject is no longer at the heart of photography. It is as if the artist was directed by the bird.

The series Stagnant Water (for example the River Thames) by Roni Horn and The sound of a distant wave by Arne Schmitt are both invested with banality. For Roni Horn, the Thames shot at any time, in its marine meanderings or its muddy jaundice achieves the depth of contemplation before the surf, this coming-and-going of the water. Arne Schmitt captures boulevards without beauty, he looks at daily life, lived by all, in our cities without poetry, a photographic work that, paradoxically, will be forgotten ten minutes later. Memory sometimes retains the ordinary but never its repetition.

Finally, the exhibition closes with an opening. The photographic also thinks of itself as an experience. In his works, Lewis Baltz is showing industrial and technological locations in California. Life is hardly present, humanity seems to have fled as does poetry and yet all that seems to remain is the work of humans. From these, photography makes it possible to grasp the pitfalls between the importance of these industrial places on a given territory and the impossible incarnation of man in these dull places.

As for Jean-Luc Moulène and his series The Look-out,from 2004 to 2011, the artist followed the fortunes of a Chinese plant that sprang up in the Bercy neighbourhood. Torn off, trampled on, concreted over, it pushed through the cracks in the bitumen and became the inert and amused witness of the affairs of mankind.

The screening of Waiting for the teargas by Allan Sekula is also a powerful moment for the exhibition.The American photographer had attended the first anti-capitalist demonstration against the WTO in 1999. Uniting dockers, feminists, ecologists, onlookers, the demonstration had surprised the authorities, little used to this kind of protest. The political and security response had taken several days to be put in place, time during which the demonstrators had to hide their boredom. The photographic series shows the idleness of an embryonic movement, put together after the fact in the violence of the opposition to the forces of law and order. If the series uses the codes of photojournalism, it criticises vividly its sensationalism and finds echoes in the thoughts of Régis Debray. In From humanism to the humanitarian (Conference at the French National Library, 1993), the philosopher denounced the shift of humanitarian photography that was based on “an imposed subject: the horror […]. The injury, the destruction, the suffering, the poverty, illness, hunger: the immediately pathetic nature of the referent relieves the shooting of any apparent effort of staging”. Seen this way, Allan Sekula’s series also makes it possible to foresee the drifting of the photographic, the voyeuristic gaze becomes the prerogative of a certain photojournalism, restoring the inhuman but, paradoxically, participating in its neutralisation.

The exhibition’s only deviation (successful), the series Telegraphic limit (2007-2012) by Trevor Paglen. The American artist studies the imagery generated by drones, telescopes and electronic surveillance systems. Using the same equipment he turned the lens around and pointed it at the sources of power habitually using these technologies: the army, the intelligence centres. The photographic seems to be neutralised here, the image becomes imagery, it essentially conveys scientific information, no longer knowledge, wisdom, nor emotion. This opening of the exhibition announces the questions to come in the second exhibition, forecast for 2019.

Arthur Dayras

Seizing the photographic

October 7, 2017 to January 7, 2018

S.M.A.K.

Jan Hoetplein 1

9000 Gand

Belgium