Sebastião Salgado is an icon to photographers around the world although this incredibly unpretentious man, who has created some of the most extraordinary, and important, imagery of our time, would probably not identify with that label.

In March I had the enormous privilege of interviewing Salgado about his latest epic project: Genesis, which is both a book and touring exhibition. To me, Salgado is like the Mick Jagger of documentary photography, so the opportunity to speak to someone whose work I admire enormously was at once exciting and somewhat nerve-wracking. But his deep passion for the work quickly dispelled any sense of celebrity.

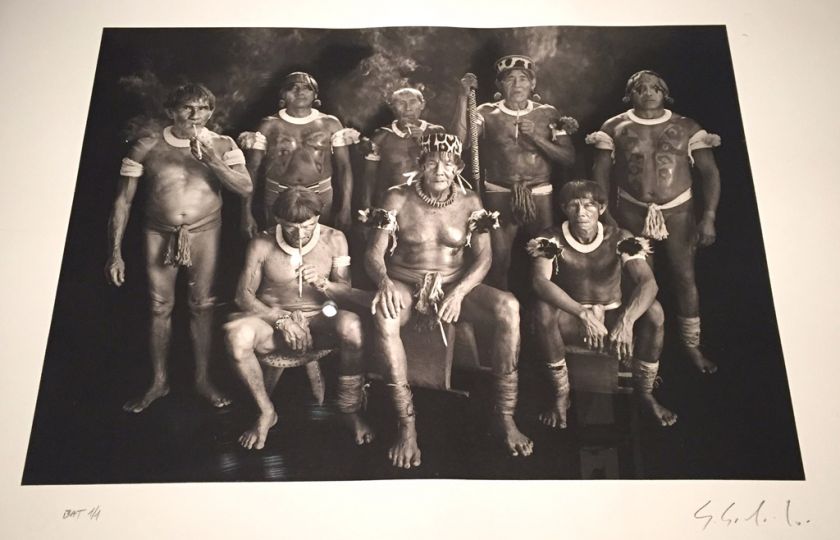

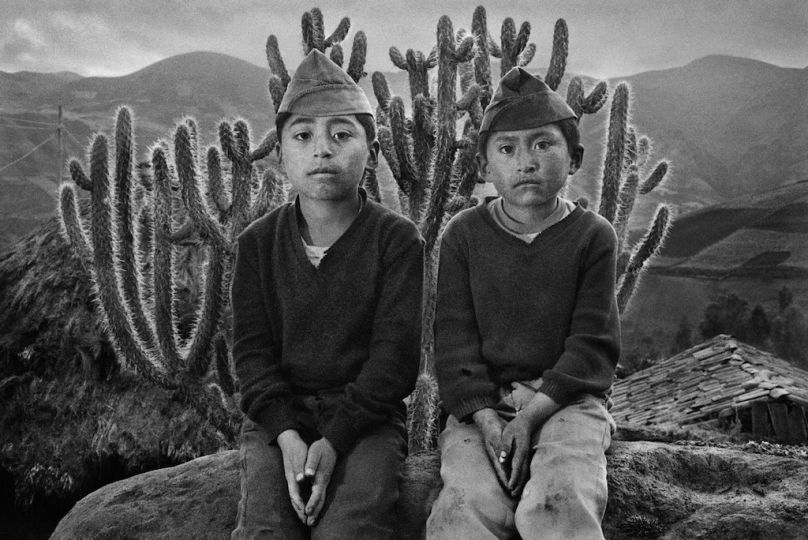

Genesis is an eight-year project that has taken Salgado to 32 countries in his search for the most “pristine locations” left on earth, and for the people who are still living in harmony with nature, as they have done for millennia.

There has been a hiatus of several years between the creation of this work and his last long-term project, Migrations, a collection of images spanning 40 countries; profound visual evidence of humankind’s will to survive, and also of a cruelty beyond measure. He tells me that after the emotional weight of Migrations he required time out.

“I spent six years working with refugee and migrant populations in very tough situations. In Rwanda I saw so many incredibly violent things, brutality at a level you cannot imagine, such total violence. I started to become sick. I saw so many deaths that I started to die.” It is more than a decade since Migrations was completed, but the tremor in his voice is still evident as he recalls experiences that have left him deeply affected.

Salgado says he and his wife Lélia Wanick Salgado, who is his partner in all aspects of his life, “retired a little bit in our place in Brazil on land we had received from my parents. This big farm is where I was born, it had been more than 50 percent rainforest, but when I received what was left, it was less than half a percent of rainforest. All my region had been destroyed in order to build modern Brazil, destroyed as humanity has done everywhere on the planet. Lélia had the idea of replanting the rainforest . So we started our environmental project to restore our forest not knowing that we were becoming environmental activists”.

They consulted a friend who was knowledgeable in forest restoration and he estimated that 2.5 million trees of more than 200 species would be required to revive the ecosystem that had existed previously. Salgado says, “we are not rich people, so we began to raise money from many different places and we transformed this land into a national park”. Over the following three years hundreds of thousands of trees started to grow, and the water came back, as did birds, mammals and other rainforest animals.

He tells me that the restoration of the rainforest is now almost complete with two million trees in the ground as of December last year. “We now have more than 177 species of birds in our forest, and the jaguars are coming back. Our forest in Brazil has become one of the biggest environmental projects in the country. We have also created an educational centre, Instituto Terra, and the biggest nursery for native plants of our region with a capacity to produce about one million seedlings a year of more than 100 different species. It has become an incredible project. And now our publisher Taschen is going to offset the carbon it takes to produce our book so we can do even more. This project started as an accident…” he trails off and I can hear in his voice that he is still amazed by what they have achieved.

As Salgado watched the rainforest recuperate he says, “the life started to become stronger in us too. And I had an idea to go back to photography, but no more did I want to photograph the only animal I had focused on all my life, us. I had an idea to photograph the other animals and to photograph the landscape, and yes to photograph us, but us from the beginning when we lived in harmony with nature. We wanted to do a new presentation of the planet to show the people how incredible our planet is and so I spent eight years to tell this story”.

The logistics behind Genesis are almost as impressive as the final outcome, a feat Lélia describes as a “marathon”. A mixture of donkeys, boats, planes, balloons and trucks afforded transport. Many journeys had to be done by foot and timing was worked around small windows of good weather – summer in Antarctica and the Artic, before the rains in Indonesia or the floods in Brazil. Salgado travelled in two-month blocks making four trips a year for eight years. He, Lélia and the team at Amazonas Images, the Salgado’s company, worked tirelessly researching to plan the scope of Genesis. Next came funding – a project of this scale is expensive – and many editorial partners and organisations were enlisted to support it. Finally in 2004 Salgado was ready to make his first trip for Genesis, to the Galápagos Islands, which Lélia says was “a logical starting point for a look at our planet’s earlier life”.

After each trip Salgado would return home to Paris with 10,000 images. Shooting with both film and digital, each image was assessed, without the aid of a computer – he doesn’t use one. The end result is an extraordinary collection of more than 200 black and white photographs (he doesn’t shoot in colour). Taschen has published Genesis, the book, with the exhibition of the same name currently showing in London at the Natural History Museum. Lélia is once again editor, curator and designer of the collection, which is divided into five sections: Planet South; Sanctuaries including The Galápagos, Indonesia, Madagascar and Papua New Guinea; Africa; Northern Spaces and; Amazonia and Pantanal.

Planet South – “Twice the size of Australia, Antarctica seems even larger on maps because its landmass lies hidden beneath a vast frozen blanket that stretches hundreds of miles into the southern oceans. The coldest, driest and windiest of the world’s five continents, Antarctica’s fierce ecosystem reaches as far as the Falkland Islands, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, and the southern mountains and coasts of Argentina and Chile. And yet in this harsh environment, the cycle of life goes on”.

Sanctuaries – “Isolated islands offer ideal conditions for the development and survival of endemic flora and fauna. As a result, unique animal and plant species are often concentrated in small geographical areas. Their principal threat is the encroachment of human settlements. While some ancient tribes still live “inside” nature much as their forebears did this harmony is also often disturbed by modern man. Thus, in what were once safe refuges, ancestral ways of life, rare animals and unique plants are inescapably threatened with extinction”.

Africa – “Since my first visit to Niger, in 1973, I have always felt a deep attachment to Africa. Even when assignments meant confronting crises of famine, drought or war, I jumped at the chance to return. With Genesis, however, I had an altogether happier experience – that of recording a seemingly eternal Africa, one of ancestral tribes, majestic landscapes and breathtaking wildlife. The continent may be vast and varied, yet its many ecosystems remain uniquely African”.

Northern Spaces – “The North Pole stands on ice, surrounded by hundreds of kilometers of frozen ocean, but the Arctic Circle itself is ringed by the northernmost regions of the Americas, Europe and Asia. As a result, the Arctic ecosystem reaches well into Alaska, Canada, Greenland, Scandinavia and Russia. In some areas, the ice gives way to permafrost and tundra; in others, volcanoes, glaciers and canyons recall the geological convulsions that marked the formation of the earth. Yet, for all this, tenacious animals and peoples have chosen to live there”.

Amazonia and Pantanal – “From space, the Amazon River and its tributaries resemble a giant tree of life. Indeed, the entire Amazon basin represents life in myriad ways: as a global lung, as the source of 20 percent of the world’s fresh water, as home to uncounted species of flora and fauna, and as a refuge for scores of Indian tribes. On its peripheries, though, logging, cattle farming, mining and urbanization are slowly eating away at the jungle. Burned forest and cleared land have now left vast scars on what was once an uninterrupted carpet of green”.

In addition to the majesty of the photographs is the narrative. This textural analysis gives Genesis an even greater richness that combined with Salgado’s “eye” becomes a document of significant historical value. In viewing this book one cannot help, but be moved by the extraordinary beauty of nature and to understand what we stand to lose should we ignore the reality of our species’ impact on the planet.

In thinking about the highlights of this eight-year opus, Salgado recalls the 850km trek he made from one of the holiest cities in northern Ethiopia, Lalibela, to the town of Gondar, situated at 2300m and famous for its castles and church architecture. “The walk took about two months through the mountains,” says Salgado. “It was a unique experience and I walked because there are no roads. These tribes live as they did in Old Testament times and produce everything they consume, including food, textiles and farming tools. After the first week of walking I was very far from any towns and roads, and I was inspired to be part of this society that was completely living in another era, and in harmony with the land. They have very sophisticated agricultural practices and artisans and craftsmen are very important in this society. It is so beautiful and walking there you understand how these lands, these rivers all ran to Egypt and made the glory of Egypt, it was incredible”.

He tells how at the end of a long day’s walk he was so tired, and someone took off “my shoes to wash and cleanse my feet in the oldest symbolism of the humility of the Christians, you know, it was incredible. For me it was the most fabulous walk, you cannot imagine how beautiful it is really, the most pristine and beautiful place of the world”.

There were, of course, explorations that left him frustrated. He says he has no pictures of the Himalayas, but not for lack of trying. “I did a walk along the border of Butan and China, more than 550 kilometres across very high mountains and it was raining, monsoonal. Two months in the rain, that for me was very tough, it was a very long walk, and I became very tired and had no pictures. That was the most difficult for me in this sense, but I wanted to see the most pristine places on the planet and they are not easy to access. If they were easy, we would have already destroyed them”.

Surprisingly there were few interruptions to his voyages – in a forest in Irian Jaya, Salgado fell ill with malaria and had to cut short that trip. And deep in the forests of Papua New Guinea, Jacques Barthélemy Salgado’s assistant had to be evacuated after his leg became infected from a bee sting – but much of what was planned went ahead without too many aberrations and Lélia and their son Juliano, a filmmaker, joined Salgado where and when possible.

At one point there were concerns over funding “when part of our original editorial partners could no longer sustain Genesis”, but VALE, a Brazilian company that is also a supporter of Instituto Terra, stepped into the breach and Genesis continued as planned.

We digress from talking about Genesis for a moment to discuss the future of documentary photography in the wake of the decline of print editorial. “I believe the future is there for the committed documentary photographer. With the Internet, humanitarian organisations and NGOs who have magazines that need pictures, and editorial work, we have a base that is now probably bigger than before, but it is challenging,” he concedes. “Lélia and I teach documentary photography in a school in Japan and we are seeing a lot of young photographers becoming very strong. When a young photographer tells me they want to do documentary photography, I tell them they must go back to University, study a little bit of sociology, anthropology, geopolitics and economics, in order to understand this planet and their society, so they can create a life of photography based in historical knowledge”.

The breadth of a project like Genesis wouldn’t have been possible without an understanding of the cultural and environmental issues that exist in the contemporary world. Genesis is a book that you will return to over and over again as the grandeur of the content is such that each picture requires its own time for reflection. For me the power of the still photograph is in allowing the viewer time to explore the image at their leisure, to revisit the familiar and to uncover the new. I ask Salgado for his thoughts on still photography.

“The still photograph is very important, more so than documentary video or film,” Salgado tells me. “I have a son who is a filmmaker and I see what he does and it is very interesting, but film shows history from the beginning to the end. Documentary photographs are different. Each photograph is a single image that must represent all the emotion, and all the light; it must show the life being captured in that photograph. When you do a stop in photography, that photograph becomes a kind of symbol, it is much more powerful than a full series of images that compose a video, which is a different way to tell a story. We need the still picture in the sense that we look to them and we don’t need translation, we don’t need text, we don’t need anything. I believe this is the power of the still image. And now with the Internet and the style of using a lot of images, the symbolic picture, the single image, is very powerful”.

We turn back to Genesis. After eight years immersed in this project, I ask him how he feels now it is completed. “ I want to go again,” he laughs and it is immediately obvious that Genesis has indeed rejuvenated his soul. “Because you see for Genesis I am finished, but I want to do a few more things . I’ll give you an example. I work a lot in the south of the planet and I want to complete that. I have a big wish to go to New Zealand, to the islands and to complete my set of pictures of the landscape in the south. I worked a lot for the Genesis project there, and I had worked before in this area. But I want to go back to see the mountains, I want to walk on that ground again. I saw so many incredible things that I want to connect with the planet and the environment, to me that is life”.

He says he’s always had a connection to nature. “Absolutely always. I was born on this farm in Brazil, I tell you I was born in a paradise, I had long walks in the forest and swam in the rivers with Caimans (a large aquatic South American reptile) and always in my life, look at my pictures, the best of my pictures they are of the countryside, so country for me is very important. For Genesis I walked a lot, climbed a lot, in my search for pristine locations. What I did for myself in going to these marvelous places is the biggest gift a person can receive”.

Whereas Migrations was “a very disturbing story”, Genesis is a celebration of the wonders of nature, but he cautions that “it is also a warning, I hope, of all that we risk losing. I hope that the people who see Genesis will understand we have an incredible planet, a planet that we must respect and protect. We must also have respect for our species and for the other animal species. We destroy too much and give too much to the modern part of our society. If we want to continue to live here we must restore order to what we have destroyed. Everything is alive on our planet. We must integrate again with our planet, or one day our planet will push us out completely, and we will disappear as a species. We are breaking this essential link that we have with nature. We are nature, but if we come back a little bit to nature we can be integrated with the planet I am sure”.

Earlier in the interview Salgado had told me he was not a rich man. Perhaps in the way the Western world views riches that may be true, but in the things that we should hold dear – compassion, humanity and respect for ourselves, other creatures and Mother Earth – he is abundant.

Alison Stieven-Taylor

Exhibition

Genesis

Photographs by Sebastião Salgado

Until 8 September, 2013

Natural History Museum

Waterhouse Gallery

Cromwell Road

London SW7 5BD

UK

Book

Sebastião Salgado Genesis

Published by Taschen

Hardcover with 17 fold-outs, 9.6 x 14.0 in.

520 pages