In the context of the Lithuania Season in France, The Eye of Photography met with author and exhibition curator Sonia Voss, who has been interested in the Lithuanian photography scene for several years and is curating several events this fall.

How did you become interested in Lithuanian photography?

I came to Lithuanian photography through my background as a film enthusiast. I come from the film world, where I worked in film production and financing for several years. Early in my career, one of the cult figures of auteur cinema was Šarūnas Bartas. When I moved into photography, I developed an exhibition project around the photographic work Bartas was doing alongside his films, which was presented in parallel with his retrospective at the Centre Pompidou in 2016. Shortly after, the Lithuanian Cultural Institute and the French Embassy contacted me to prepare an exhibition of the photographer Antanas Sutkus, a master of Lithuanian photography. The initial project ultimately didn’t materialize, but it marked a turning point for me. I maintained a connection with the country, where I was warmly welcomed in artistic circles, particularly by the highly committed and dynamic women who lead cultural institutions. I also forged relationships with members of the Lithuanian Photographers’ Union. Over the years, I continued to explore and familiarize myself with their creations through publications and exhibitions in Vilnius and Kaunas, where I was invited to present my own projects.

What are the distinctive traits of Lithuanian photography?

Lithuanian photography has a fascinating historical depth, with a tradition dating back to the late 19th century. However, the uniqueness of Lithuanian photography really asserted itself in the 1960s with what is known as the “Lithuanian School of Photography,” whose representatives include Antanas Sutkus and Aleksandras Macijauskas. Their photography is humanist but differs from that of other countries due to its intense focus on ordinary people and rural environments. In the Soviet political context, where the hero was an omnipresent figure of propaganda, focusing on everyday men and women, without glorifying their social role, was already a strong, almost political, statement. This theme of the ordinary is expressed through powerful and expressive images, imbued with a psychological and existential always radiant dimension.

What about the next generation, which you said was your entry point into Lithuanian photography and reflects the major themes of East German photography that you were also interested in?

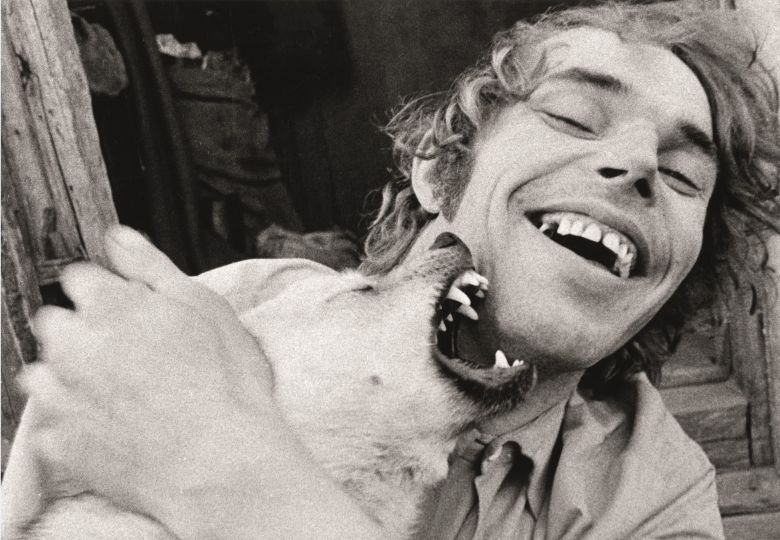

The next generation, emerging in the late 1970s, distinguished itself by a certain detachment from the coercive context of the time, propaganda, and the monotony of daily life. This led photographers to adopt new artistic strategies, more introspective for some, while others turned toward self-staging, creating almost fictional, sometimes provocative images. I’m thinking particularly of Violeta Bubelytė, who gained attention with her nude self-portraits and theatrical poses, or Rimaldas Viksraitis, who won the Discovery Award at the Rencontres d’Arles in 2019.

These two generations form the two major parts of the exhibition “The Forms of Things, The Forms of Skulls, Forms of Love,” which you are preparing for Paris Photo. It will feature over one hundred prints from two important collections: the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF) collection, which we cover in another article, and the Centre Pompidou’s collection, acquired through a significant project. Could you tell us a bit about the Centre Pompidou collection?

Florian Ebner and Julie Jones, curators at the Centre Pompidou’s photography department, traveled to Lithuania in 2023 and 2024 in preparation for the Lithuania Season in France. They were very impressed by the meetings they had and the works presented during these two research trips. It turns out that Lithuanian photography is almost entirely absent from the Centre Pompidou’s collections—except for Moï Ver and Izis, who are special cases since, though born in Lithuania, both emigrated. In complementing other national collections, specifically the BNF’s, they naturally focused on the generation that followed the Lithuanian School of Photography, to explore the younger “rebels” of their time like Bubelytė and Šeškus, as we’ve already discussed, as well as other artists such as Gintautas Trimakas or Algirdas Šeškus.

You complement the Paris Photo exhibition with prints from the Lithuanian Photographers’ Union collection and contemporary works. Tell us about this scene.

After the fall of the USSR, and especially after Lithuania joined the European Union in 2004, many Lithuanian artists left the country to study or work abroad, particularly in London, Vienna, or the United States. So it’s difficult to speak of a “scene” in the traditional sense. However, these artists form a diaspora that remains deeply connected to the painful history of their country, which has been profoundly marked by successive occupations. Most Lithuanian families have experienced trauma linked to the country’s history, and the younger generations are very concerned with this. But it’s not their only focus. Among contemporary artists, some explore environmental or body-related issues, while others work on collective memory or specifically on the history of photography. There is a continuity between the past and the present that I seek to highlight through this exhibition.

I’d like to end by discussing another exhibition you are curating, which is taking place at the Hôtel La Louisianne as part of the PhotoSaintGermain festival. It focuses on Antanas Sutkus and connects with the Saint-Germain-des-Prés neighborhood, concentrating on a very specific moment in the photographer’s career: his meeting with Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir.

Antanas Sutkus was still a young photographer in 1965 when a major event occurred for the Lithuanian cultural world: the visit of Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. A delegation of writers was assigned to accompany the couple during their travels. Sutkus found himself among them. Their itinerary brought them to Nida, on the Curonian Spit, where Sutkus took a now-famous photograph of Sartre, walking pensively on the sand dunes, leaning into the wind. This shot was long attributed to Cartier-Bresson, and Sutkus had to send his negative to the Parisian agency that had published it to prove that he was the author. This portrait became famous; it even graced the cover of Libération upon the philosopher’s death. What is less known is that Simone de Beauvoir was originally in this photograph, but it was cropped to focus on Sartre. The exhibition presents 12 prints from this series. It allows viewers to discover this beautiful work and to once again see the presence of Simone de Beauvoir. In fact, it is presented in a room called the “Simone Space.”

More informations :