Leiter’s nudes have a spontaneous and romantic quality, like the scattered pages of a diary, or stills from early movies. These women are completely natural in front of Leiter’s camera, and uninhibited. They are waking up, taking a bath, applying lipstick or makeup, smoking the first cigarette of the day. One is pensively holding a cup of coffee, another still has rollers in her hair, her face creased by the pillow; one is rolling down her black stockings, another is lying on the floor against a background of slightly out-of-focus and crumpled news- paper sheets. They are dressing, undressing, pulling a skirt’s zipper, unbuttoning a blouse, or simply daydreaming. Leiter photographs two women in bed together, one dressed in a man’s shirt, the other in a feminine negligee. Several women are masturbating, a rare occurrence in classical nude photography but one found in Schiele’s drawings or Balthus’ paintings.

Leiter’s gaze is not that of the typical male: the women can be in turn shy, aggressive, or playful, but they always appear to be partners and full par- ticipants in a give-and-take, a dialogue, very aware of the photographer and the photograph that is being taken. In other words, these are not traditional nudes but rather portraits of women who happen to be in the nude. The psychological component is as strong as the erotic, in balance with Leiter’s formal concerns.

Leiter is not in search of an idealized beauty. He allows some awkward poses into his images, and he loves imperfections: the crease lines created on the skin by underwear or sheets, the hair rollers, the open mouth or dazed expression of a woman who seems as if she is just awakening from a dream. He looks for unguarded moments, and his friends let him in.

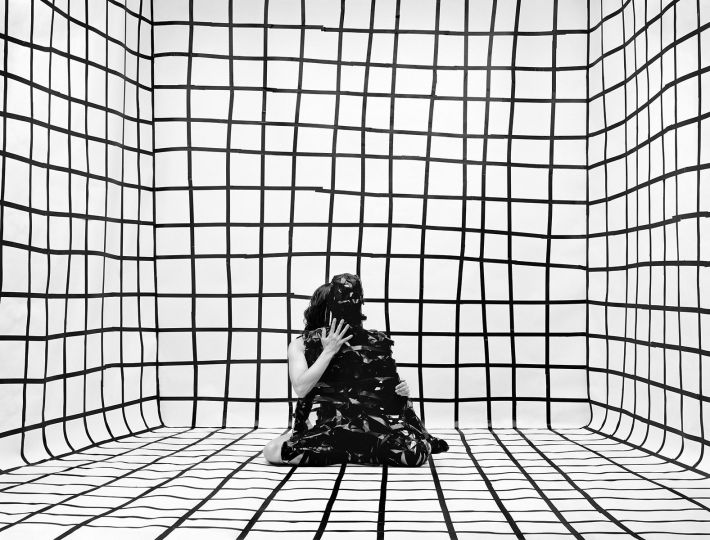

The pictures are always taken with natural light and in Leiter’s room, with the everyday environment and its objects playing a strong part. He sometimes includes a few of his prints, tilted against a wall or scattered on the floor. The pictures are often taken through the narrow opening of a door or the crossed lines of his empty easel, devices that seem both to create a distance and pull us in, and recall the setup of Leiter’s pictures of the El train taken from above.

The images can be a reflection as seen in a mirror. Sometimes there are two mirrors, so that another out-of-focus reflection floats into the second mir- ror, like a dream or a ghost image of the main scene. A half-open door, or a rectangular mirror, builds frames within the frame, as in a Vermeer scene.

Sometimes, the pictures are shot from above, blending a woman’s body with the patterns of a sheet, as in a Vuillard painting, or from a very low vantage point, with the photographer crouching on the floor or at the foot of the bed. In that way a flattened perspective, with everything on the same plane, is created. However, the women are never made into objects themselves.

Leiter uses a shallow depth of field, lights that are low but natural, a slow film. Some zones in the image are deliberately left out of focus, like a phrase misheard, a whisper, a memory half forgotten. Sometimes, the woman’s silhouette is backlit, obscuring details. Leiter seems to suggest that our perception of the moment is always incomplete, that however hard we look, reality and truth evade us.

Monotypes, which are images created by rubbing into a ground coated with dark ink so that planes of light emerge, are created by subtraction. It often seems as if Leiter’s photographs, with deep chiaroscuros and faces often concealed in shadows, are created the same way. As in Vuillard, Degas, or Bonnard’s monotypes, Leiter’s nudes emerge from the dark, embodying the passage from darkness into light. (These painters also took snapshots of their models.)

Leiter’s nudes have a marvelous transitory quality. They are not about solidifying the present into a sculptural form—as in Edward Weston or Bill Brandt’s images, for instance. They are romantic, cursive notations of time and space; they are about transformation, about the fleetingness of the instant, about a never-ending search for beauty.

Leiter’s idea of beauty is not conventional but found in surprising angles, compressed perspectives, and quirks of sight. It could reside in a reflection or a body fragment: the breast caught in a mirror as if by chance; an armpit; the roundness of a cheek; a shoe dangling from a pointed foot, ready to fall; an open hand, fingers splayed, surging from tangled sheets an ambiguous gesture that could invite or repel. A woman’s back and neck are fully expressive, reflecting her mood. One photograph, with the subject’s fully tilted neck and arms hidden behind her back, may be a reference to Man Ray’s 1920s images.

Rather than leaning toward Greece’s classical ideal, Leiter seems to me closer to the Japanese artists, for whom a woman’s neck, a white column rising beneath a crown of black hair and above the silk of a high kimono collar, embodies sensuality. Somehow I was not surprised when I learned that Leiter greatly admired Japanese calligraphy. His intuitive, fast method of photographing is not far from that art, where letters have to be painted quickly, without remorse or hesitation.

Looking at the writings caused by light and shadow that play over the women’s bodies as if their flesh was Leiter’s other canvas, I then realized that these markings, these striations, swift and soft like brushstrokes, seem to replicate those of his abstract inks on a thin Japanese cream-colored paper, once offered to his lover as a birthday gift.

Further, this made me understand the secret connection between four distinct areas of his work: the black-and-white nudes, the painted nudes, the street scenes, and the paintings. It seems to me that in each case, but with diferent means, Leiter explores the passage from representation into abstraction in the black-and-white nudes, with the markings of light and shadows painted on the women’s bodies; in the painted nudes, with the color strokes that redefine and blur the contours of the bodies; in the street scenes, by favoring snowy weather, fog, and rain, or scenes photographed from behind glass, thus reducing the body and the buildings to blurred silhouettes or pro- files; in the paintings, letting representation dissolve into abstract color fields, plowed with vivid furrows, hatched with nervous lines.

In the 2012 documentary about him, In No Great Hurry, Saul Leiter says, “There are the things that are out in the open, and there are the things that are hidden, and life has more to do, the real world has more to do, with what is hidden. You think?”

We can keep looking at Leiter’s nudes, but in the end these tender and graceful depictions of “the things that are hidden”—images that Leiter rarely showed in his lifetime—retain their essential mystery, defying interpretation.

Carole Naggar

Carole Naggar has been a photography historian, university professor, and independent curator since 1971. She lives and works in New York. The books under review were browsed at Paris Photo, Off Print, Polycopies, and Paris Vintage between November 8 and 12, 2017.

Saul Leiter, In my room

Steidl

Howard Greenberg Gallery

41 East 57th Street

Suite 1406

New York, NY 10022