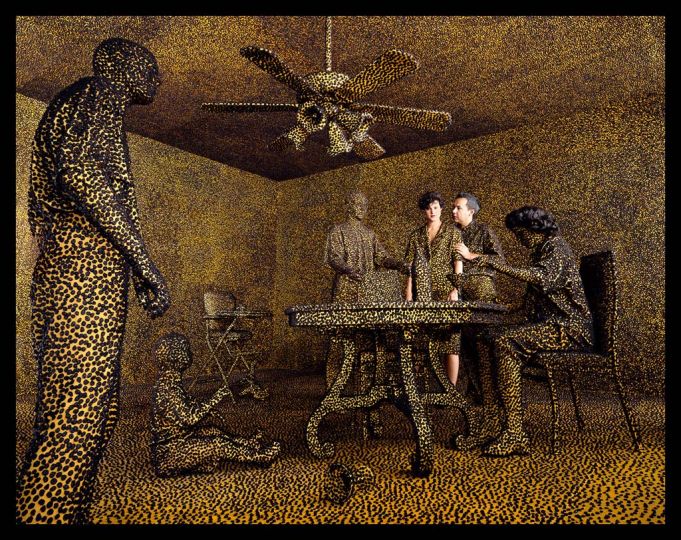

Sandy Skoglund creates surrealist images by building elaborate sets or tableaux, furnishing them with carefully selected colored furniture and other objects, a process of which takes her months to complete. Finally, she photographs the set, complete with actors. The works are characterized by an overwhelming amount of one object and either bright, contrasting colors or a monochromatic color scheme.

What’s your process when constructing a tableau? Where do you start?

Sandy Skoglund: I usually start with a very old idea, something that I have been mulling over for a long time. Sometimes it is a theme, but usually it is a distinct visual sensation that is coupled with subject matter. It feels like a bright little moment of excitement in my chest when I think about the idea. Then, it is a question of action and pursuit and perseverance. Since I prefer subject matter that is usually familiar and common, I often ask myself if there is a new way to approach it. I hope for something to come straight out of my imagination.

What steps do you take when constructing a set so that it renders properly in an image? Do you ever get more attached to the sculptural elements than the actual photographic product?

I do take elaborate steps to see how the sculptural elements and materials are translating photographically. I take photographs as I go along to see if the imagined photo image is still on track, or if it is starting to run amok. So I am committed to the photographic result from the beginning, but the sculpture is equally important and compelling to me. So, yes, I do get very attached to the sculptural elements. I have never thought of them as just props.

You studied painting. How did you get involved with photography?

I became interested in photography in the 1970s, after graduate school at the University of Iowa. When I moved to New York in 1972, photography was exhibited by conceptually driven artists to document their performances and events. I am thinking of John Baldessari, William Wegman, Robert Cumming, Vito Acconci, and many others. There was an irreverent spirit in that work that I connected with. It seemed like they were using photography outside of the traditional canon. Since I had never studied photography in school, I felt that I could just jump in anywhere. I discovered that I loved the craft and science behind the medium, and decided to pursue it.

Your videos are very chaotic as well, are you intrigued by disorder, or are your pieces more calculated than your audience might perceive?

The concept of order and disorder are at the heart of my work. I love working meticulously to make something that appears to be chaotic. Also, chaos is a matter of perception. In my piece Fox Games, the foxes probably do not feel that they are creating chaos by jumping around on the carefully arranged tables. They are just doing what they would normally do in an environment, but with different obstructions and plateaus.

What does the repetitive nature of your subjects represent? Why not just one spoon, one cat, one fish?

I cannot help but see repetition in two contradicting ways: the abundance of things as a beautiful aggregate that is greater than the parts, but also the overabundance of things as alarming and invasive. I think the repetition is derived from my early history with Minimalism, in which repetition was used toward existential philosophical goals. Here I am thinking about the work of Agnes Martin, Donald Judd, Carl Andre, Sol Lewitt, and others. In their case, the repetition was reduced to basic components.

You often use animal iconography in your imagery. In what ways is the interaction between human and animal symbolic?

I like to think about my photographs in terms of, “who is looking at whom?” As much as we talk about the “male gaze” we could also talk about the “human gaze” when it comes to the living world as a whole. So I am often trying to undermine the normal human gaze when working with animals.

Can you describe one of your favorite icons that you have utilized in your work and its cultural significance?

I think of popcorn and cheese doodles as some interesting icons of the American pop culture experience. They speak about natural and unnatural, and they reflect the American cultural contribution of “fun” to the global cultural landscape. I think it is the element of fun that is so attractive about American culture, even when we are being suffocated by it.

Why do you always choose to include at least one humanoid figure in each photograph?

The human figure frames the situation into a narrative and creates a sense of scale.

Your use of saturation and contrast has given your work acclaim in both the fine and commercial arts. How do you think concepts of commercialism & American sensibility affect the way your images are perceived?

Starting in 1978 with a series of Food Still Lifes, I was deliberately trying to make images that were commercially uncommercial. I looked carefully at advertising photography, which was very specialized, slick, contrived, and polished. I decided to work that look and feel into my own studio constructions by using a large format camera and elaborate lighting setups. I still find very hi-res detailed photography to be the most satisfying to look at, but it no longer has the same “commercial” feel because all digital photography has migrated us toward a detailed view of things: witness television screens that show every blemish.

You have described your thoughts & decisions on the materials that you use as “schizoid”. Could you elaborate on this?

I think I meant deliberately impulsive and irrational. I try to create contrast and conflict with everything I work with: color, materials, subject matter…. My philosophy is that you really see something for what it is when you are presented with its opposite. You really see a blue color best when it is opposed to orange. You really see chaos best when it is situated in an orderly setting.

The process seems very delicate. Have you ever had any accidents or mishaps during the process that have set you back? Can the process itself become chaotic?

Yes, all the time. I will wake up in the morning full of excitement to try some new color or material, and then by the end of the day I will realize that it is just not working. There is a tremendous amount of “wasted” time and materials to get what I want. I think it’s an important part of the process: to throw things out.

In a lot of the photos, the humans either don’t pay attention or barely care about all the craziness around them. Is this meant to say that the chaos is accepted?

Well, I think that maybe the chaos is not seen or recognized.

Much of your work seems to involve meticulous arrangements in some way, even digitally in True Fiction Two. What is it that you find so fascinating in the process of arranging?

I think that the process of arranging is like “nesting” just a way of making the world in your own image rather than someone else’s.

This interview was published in the issue 16 of Musée Magazine that came out in October 2016 and is available for $65.