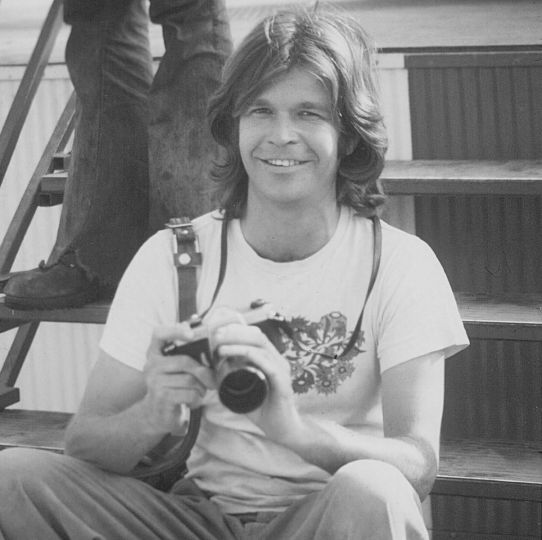

Imagine my surprise when I read the announcement of the relaunch of Camera to see no mention of Romeo Martinez. He was the legendary editor of the magazine from 1955 to 1967. He was also my mentor in photography, or more precisely, my father… A few weeks after his death in 1991, I wrote this article for Le Monde, and I’ve taken the liberty to publish it here again. I would like to thank the editors of this new review for reminding me of the importance of memory and historical truth.

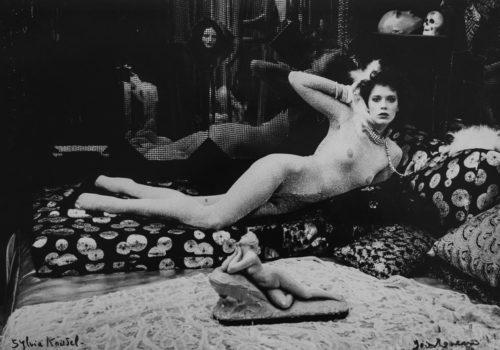

“Only morons talk about Atget without mentioning the importance of prostitutes in his work. Without them, his photos are incomprehensible.” This remark was made in 1972, at 21 rue de Seine. It was the first time I met Romeo Martinez. I was one of the morons in question, and for my ignorance I was shunned for six years.

Contact was resumed in 1978. We took to having lunch together regularly. It was the beginning of a friendship that lasted 12 years. I never had more admiration for one of my contemporaries. I had learned my lesson: I was silent, I listened, careful not to say anything with a hint of nonsense in it, so as not to arouse his Homeric wrath and be rejected again.

Romeo quickly became my “photographic father.” I discovered that it was the same for all of the photographers, critics, collectors, picture editors, curators and other photography specialists. He a rare character, warm, full of humor and tenderness. He taught us not to believe in legends and platitudes, but to make our own judgments.

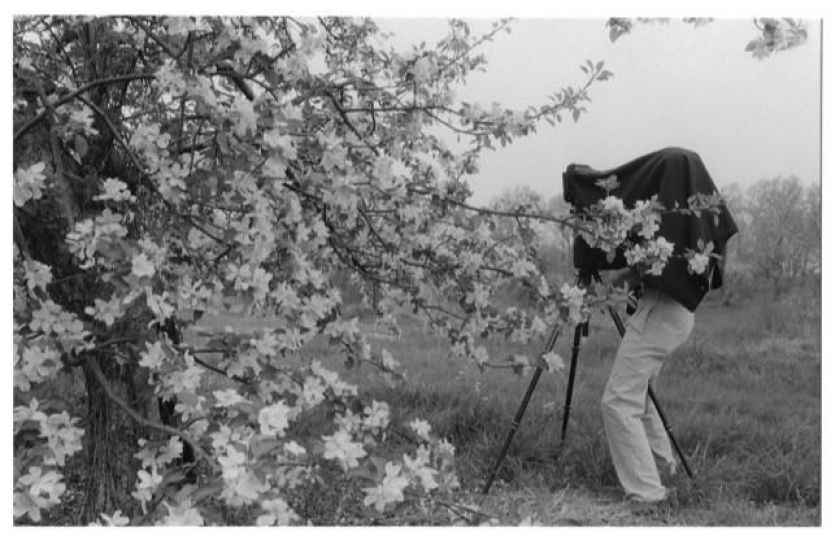

It was easy for Romeo: everything that had a name in photography since 1930, no matter how big or small, he knew —not intellectually or scholastically, not through books or magazines, but in real life. He had dined with them all, shared their joys and sorrows, their hopes and failures, smoking enormous cigars in private gardens.

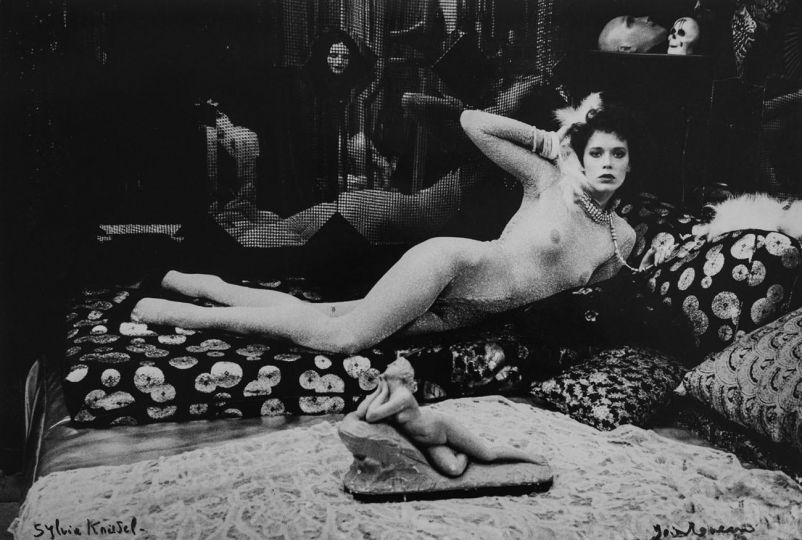

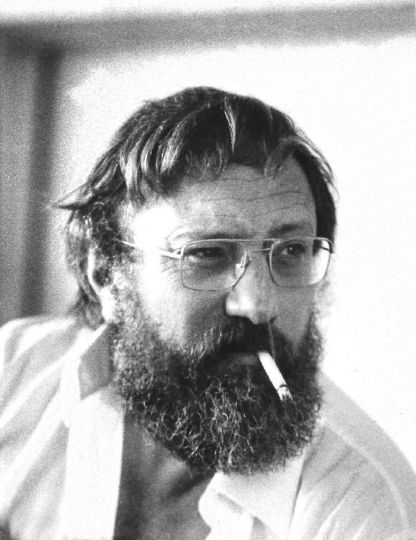

Everyone had passed through his den on the Rue de Seine: Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Doisneau, Eugene Smith, Robert Capa, Irving Penn, Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Jeanloup Sieff, Josef Koudelka, Marc Riboud, Bruce Davidson, Ernst Haas. The Italians, the Spanish, the Turks, the English. They only had one dream: to climb the uneven steps up to his apartment, pull on the preposterous doorbell, and make their way through the mountains of books at the far side of the room to find Romeo in a cloud of smoke, with his bald head and long moustache, his eye sparkling.

“I never published anyone without meeting them. I wanted to see the man first. Only then could I made a judgment about his pictures.” The legends, when he explained them, were clear and rang with truth. We cannot understand Robert Capa unless we’ve heard Romeo Martinez speak about his women and his weekly trips to the races in the 1940s and 50s to pay (or not pay) the bills at the Magnum agency. You know nothing about Eugene Smith if Romeo hasn’t shared with you his constant paranoia, nothing about Brodovitch if you don’t understand his alcoholic self-destruction.

Romeo was much more than this, by turns accomplice, father, brother, banker, supervisor and confidant. Someone is missing from this picture: Jacqueline, his wife of fifty years. Without her, he wouldn’t have made it. Romeo had no sense of money, confused until the end by the difference between old and new francs. He had no sense of deadline: Camera, the prestigious magazine he ran from 1955 to 1967, was somewhere between a weekly and a quarterly. And he had no sense of time. Sometimes he forgot to come home at night, and Jacqueline would find him sitting with Doisneau in the café downstairs.

His character lent itself to this kind of excess. Everything about him was immoderate. He was born one day in 1911 to a Spanish father and a Mexican mother on a German cargo ship, on the border of Greek and Turkish waters. When he arrived in Paris at the end of the 1920s, his family was dispossessed of its lands by the Mexican Revolution. Romeo found himself penniless, working any little job he could find. Politically, he was close to the anarchists, then during the Spanish Civil War he served as a political commissar for the POUM, which was later annihilated by the Communists.

He loved gambling, of course, the races and the casino, and formed unexpected friendships with Aga Khan and Django Reinhardt.

In 1985, in Arles, Romeo hosted an extraordinary evening on the photography of the 1930s. It was the opposite of a lecture: a tender confession full of anecdotes. Few people in the Théâtre Antique that night understood the greatness of what they were witnessing. In fact, there were only three: the American collector Sam Wagstaff, the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, and Roger Thérond, the director of Paris-Match. Romeo delivered fifty-five minutes on what was probably the richest and most innovative comments on contemporary photography. All of this was recreated with simple words which translated his enormous love for these forgotten characters: Tabard, Munkacsi, Moholy-Nagy… Then he vanished until five in the morning. He was found on a bench, explaining Kertész through his avarice and taste for women to an Italian critic.

No one today speaks to us of photography the way Romeo spoke. He died in November 1990 at 79. We became orphans. “You can’t understand Henri Cartier-Bresson until you’ve studied his childhood. Be more rigorous, dig deeper, think. The more success you have, the more doubts you should have. Otherwise, you’ll only reach dead ends.”

We miss you, Romeo.

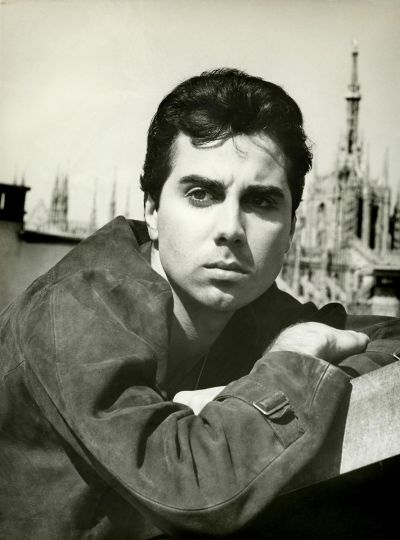

Jean-Jacques Naudet

The library of la Maison Européenne de la Photographie bears his name because he gave to Jean-Luc Monterosso all of his books in the late of 80s.