« Portraitscape of war» (Lebanon 2006)

As a freelancer without affiliations to any particular news outlet, I am not under pressure to create dramatic Front Page photographs of daily spot news events. The way I see it, my job is to find the stories in between and on the side of the main events—history’s liminal moments. These become pieces in the bigger puzzle drawn by all the players in the theatre of war: civilians, journalists, military personnel, NGO and agency workers, artists, writers, et cetera. Freelancers also have a luxury many staffers don’t have: time. Without an imminent job back home, the freelancer is free to stay and probe for longer, even when the headline news has died down. This is particularly the case in the aftermath of a major conflict. I made these diptychs of portraits and landscapes in Lebanon during, and in the aftermath of, the Hezbollah-Israel conflict in the summer of 2006 (July 12 – August 14, 2006).

I was in Toronto Canada on July 13th 2006 when I first heard that Israel had bombed the runways at Beirut’s Rafic Hairi International Airport in response to Hezbollah’s kidnapping of two Israeli soldiers—an action by “the Party of God,” designed to provoke a new war with their longstanding enemy. A week later I was in Damascus with my friend and colleague Daniel Barry. We rented a minivan and drove along endless stretches of bombed-out roads toward South Lebanon, the site of some of the most punishing bombing campaigns of the war. By early August, Israel had announced that it would consider any vehicles south of the Litani River to be a military target. This drastically limited all journalists’ mobility and therefore our ability to document the war. Nonetheless, many of us stayed in the south, along with those Lebanese unable or without the means to flee to the relative safety of the north.

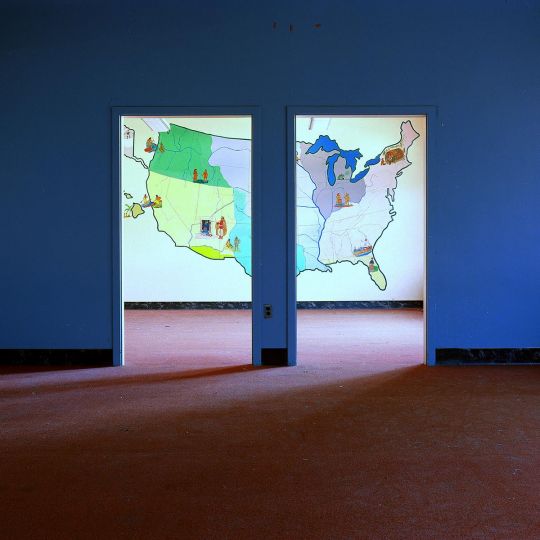

Wars are identified with specific kinds of images: the 19th century battlefields of the Crimean War and the American Civil War; Robert Capa and Gerda Taro’s portraits of Spanish Loyalists in the Spanish Civil War; the jungle warfare of Vietnam; the desert camouflaged American soldiers in Iraq and their counterparts, hooded Iraqi detainees. In Lebanon in the summer of 2006 it was images of civilians amidst the rubble of the massive bombing devastation. Many emotional and dramatic headline images were made: stunned and delirious victims in shock emerging from the rubble; mothers in emotional agony carrying dead infants crushed by collapsing buildings. On the one side there were these close-up portraits of suffering where you couldn’t get a good perspective on the context; on the other side there were wide shots of bombed out villages where human figures were tiny specs in the distance.

After the United Nations-brokered ceasefire took effect at 8:00 AM on August 14th, I set out with some colleagues to the southern border to have a look at regions we’d been cut off from for the previous weeks— Marouahine, Ramyia, Aita Ech Chaab, Bent Jabail…

There was a vast swatch of destruction all along the border. I had never seen anything like it except in post-apocalyptic movies or film footage of some of the bombing campaigns during WWII in Europe.

In the aftermath of the war, people quickly got busy gathering themselves in their new reality. Those who had fled to safety returned to survey and to see if anything could be salvaged. They wandered around, wide eyed, picking through the dirt for signs of their pre-war past. In many cases, the destruction was so severe that they couldn’t find the site where their homes or apartments once stood. A kind of erasure of the markers of inhabitancy had taken place (buildings, gas stations, infra structure), rendering the familiar strange, and making inhabitants feel like strangers in their own land.

From this period we get Spencer Platt’s photograph of a bright red convertible car full of young people driving around the neighbourhood of Haret Hreik, almost entirely leveled during the war. The image won the top spot, “photo of the year,” in the 2006 World Press Photo Contest. This was controversial because some said the photograph made the victims of war appear blasé in the face of destruction and loss. But critics missed the point: Spencer Platt’s photograph was the quintessence of the immediate aftermath of the war precisely because it showed civilians in that in-between moment still unable to quite believe what they are seeing : where they are still tourists to their own tragedy.

It was in this context that, on my computer monitor back in my hotel room in Beirut, I started rearranging and creating montages of photographs I’d taken during the war— mostly bombing sites and portraits. (It should be noted that this kind of editing is only made possible in the field thanks to digital photography).

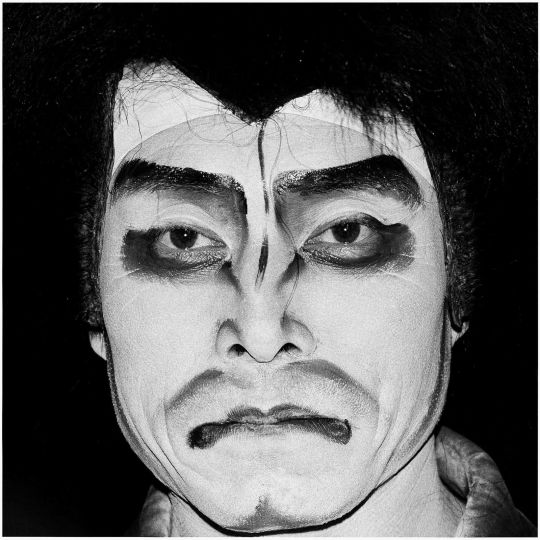

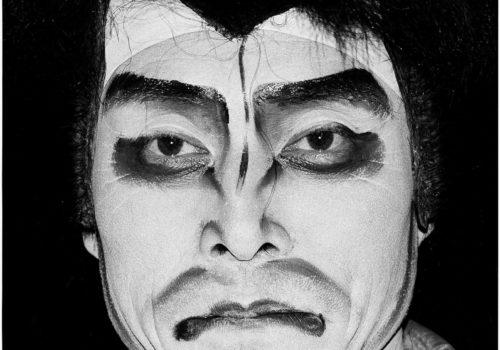

Over the next two weeks, I embarked on a series of diptychs (pairs of two) of “landscapes of destruction” and formal portraits. By photographing the landscape and the portrait separately, I could give them equal value and, importantly, equal size in the frame. The landscapes would show the broad context of the bombings and the extent of the devastation. The portraits would be full-frontal shots, with the subjects lit with portable strobes, formally composed and engaging with the camera: confronting the viewer with the “I” in their “eyes.”

All the portraits were made in situ—in the archaeological sense that everyone was photographed in the place where I first met them—so that the portraits would also serve as unmanipulated records of a moment in time. In this sense they are documents in the journalistic tradition, insofar as they adhere to realism and are not staged.

Nonetheless, from the outset my approach was outside the boundaries of traditional photojournalism, which rejects montages and also any kind of posed portrait. The hallmark of traditional photojournalism as envisioned by its early champions, like Henri Cartier-Bresson, is candid photography, without flash, without posing. In fact, journalists go to great lengths to give the impression that their photographs are candid, waiting for subjects to look away, while in fact the subjects are completely aware of being under the gaze of photographers. This is particularly the case in well-documented events like the 2006 Hezbollah-Israel conflict. Which is not to say that things are any less “real” just because subjects are aware there are cameras present!

Before the war was over, there were cries of “foul” from cynics who claimed the documentation of the war on the Lebanon side of the border was staged for the benefit of media propaganda. A famous case was an inexperienced local stringer for Reuters who, innocent of the seriousness of the laws of photojournalism, “cloned” extra smoke into a wide shot of a bombing. This transgression was used as “proof” that the media was making things up in Lebanon. Journalists were accused of importing babies into photographs to make viewers think children were being killed in the bombings. But children were being killed in the bombings! Perhaps it’s because people have seen so many Hollywood movies about war that they start associating dramatic images with “dramatizations.”

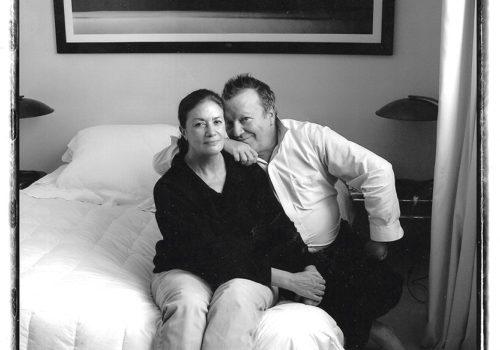

Having been in Lebanon during the war, especially in the hard-hit south, earned me a certain amount of trust and respect from the people I met, including Nariman Hamdan, who would become my fixer, translator and friend over the next weeks and with whom I’m still in touch to this day. Nariman’s brothers had been working for major news agencies during the war, so she knew something about the business of journalism, and it turned out, was eager to get involved.

On August 22nd 2006, nearly two weeks after the ceasefire, Nariman and I met Fatima Taher in Nabatiyeh outside what had once been her house but was now a confusion of twisted rebar and rubble. The night before the ceasefire had been terrifying. It’s typical of a ceasefire for both sides to go ballistic the night before they have to put down their arms and this one was no exception. All night long the skies lit up and the ground shook from the unrelenting bombardments. Fatima, who was 79-years-old, had survived a lot of wars. That night, she lay down and waited, trembling under a fig tree in her backyard: “I reasoned I would rather die under a fig tree in my garden than be crushed inside my house and scooped up from the rubble by bulldozers the next day.” Her house was hit. Fatima survived.

I made a portrait of Fatima standing in front of her house, and juxtaposed it with a photograph of a neighbouring house. “Relax and look into the camera,” I’d said. “Imagine you are looking at someone in Toronto, New York, or Paris, someone far from here, far from the war, at another moment in time.”

Photographs of subjects in heightened states of emotion can sometimes have the unintended, ironic effect of distancing and alienating viewers, who cannot identify with emotions so far from their own states of mind. Like Edvard Munch’s The Scream, the emotion is too terrifying to look at. I photographed my subjects in the aftermath, when they’d had time to compose themselves. The result is that viewers can identify more easily with them—they can to some extent imagine: This could be me. At the same time, the very restraint of emotion, juxtaposed with the unrestrained violence and devastation of the landscape has the overall effect of heightening the impact of the work.

Unlike traditional photojournalism, which favours candid portraits, my subjects are conscious of being photographed and conscious of being part of a visual construct (the diptych series I was in the process of making). They are the seeing and the seen, the subject and the object, the person gazing upon as well as the person being gazed at. The conscious gaze contains within it an intentionality that empowers the subject in a way that candid photography cannot. It can be empathetic or confrontational, or both.

Merging journalism with artistic practice, these portrayals of the impact of war raise questions about the relationship between individuals and the contexts in which they find themselves—between citizenship and inhabitancy, between the landscape and the mad-made infrastructures built there. People are both a part of and apart from the land. Caught in a place where there are aggressors on more than one side, victims of war may be defined by the conflict and denied their self-identities. They become so-called collateral damage. It is all too easy to forget that, like us, they are just ordinary people, but unlike those of us blessed with peace at home, they inhabit extraordinarily disputed lands. Here, I wanted to show the scale of destruction, but not take away from our ability to identify with the people in the pictures.

The diptychs are also a “man-made infrastructure,” a narrative device that uses juxtaposition to create tension and dialogue between the frames on either side of the diptych—related, but independent of each other.

The photographer is the interface, the first point of contact between the subject and whoever sees the photograph later. The engagement between the subject and the photographer lasts for a short time; the actual clicking of the shutter for only a tiny fraction of a second. The photograph, however, is lasting and permanent (even as it’s projected on a computer screen). It has a life beyond the moment when it was taken. It becomes the conduit or mediator in place of the photographer, between the recorded gaze and viewer’s return gaze (viewers such as visitors to museums, say eight years later in Boulogne-Billancourt France).

The viewer of the future, in another place, brings their living gaze to meet the subject’s photographed gaze. An exchange takes place, reflected back and forth and the gaze brought back to life with each encounter: It is in a state of perpetual, reciprocal flux. The viewer negotiates the fragile border between the real and the represented, between the past and the present.

Out of the ashes of destruction, all of the landscapes in these photographs have since been rebuilt, cleared of debris, buildings or fields of flowers planted in their place. Haret Hreik, today, is a small city of glass towers, more of a Hezbollah stronghold than ever before—its destruction become the cornerstone of its reconstruction. Land, even holy land, in itself has no memory. Memory is a man-made construct too, created in the eyes of the beholders, memorialized in the perpetual gaze of a photograph.

Rita Leistner

EXPHIBITION

Les âmes grises, récits photographiques d’après-guerre. Portraits : récits émergents

Rita Leistner (Liban) et Jonathan Torgovnik (Rwanda)

Until June 29th, 2014

Musée Albert Kahn

10-14, rue du Port

92100 Boulogne-Billancourt

France