To mark the centenary of Irving Penn’s birth, The Metropolitan Museum of Art has open its doors in April to a major exhibition celebrating one of the foremost photographers of our time. With more than 200 prints on display (the majority a recent gift to the museum from The Irving Penn Foundation), the retrospective is the most substantial to date and explores every period in Penn’s prolific 70-year long career. From New York the exhibition will then travel internationally with a first stop at the Grand Palais in Paris in September.

The publication of the accompanying book Irving Penn: Centennial is an occasion in itself. Not only does it feature the largest selection of Penn photographs ever compiled, including works that have never been published, it also provides essays with a fresh intellectual understanding of the deeply private artist and the human being behind the masterful photographs. The book and exhibition are created and co-organized by Maria Morris Hambourg, who founded the Met’s Department of Photographs in 1992 and knew Penn personally, and Jeff L. Rosenheim, the department’s current Curator in Charge.

The two curators were asked to select three images each from the exhibition and reflect upon them with Luncheon magazine’s editor in chief and creative director Thomas Persson. The interviews here provide fascinating insight into the artistic creation and circumstances in which these photographs were made. From Marlene Dietrich to a tribesman in New Guinea; a female nude and a still life for Vogue; a fishmonger in London and two cigarette butts – Penn’s wide-ranging subjects were all part of his worldly narrative and, as they are observed within these pages, his profound talent for storytelling.

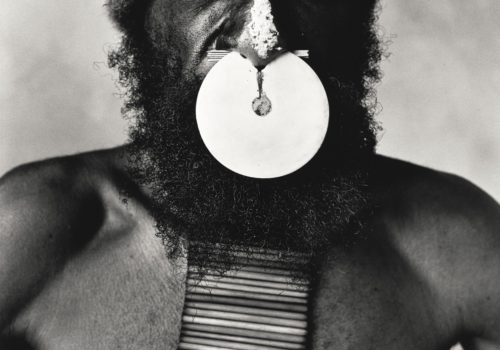

Today, we present the second part of this series with words on Tribesman with nose disc, New Guinea, 1970.

Thomas Persson: This image is so close-up it is as if we are looking right into his soul. I wonder if Penn’s series of portraits of the indigenous people from New Guinea were part of a search for human nature in its original version, so to speak?

Jeff L. Rosenheim: Perhaps but it’s really not any closer than his portrait of Picasso, which was made years earlier, or the picture of Colette. All have unbelievable visual power because of our physical proximity to their faces. We are closer than we normally are to the people we know best in life… closer than we even get to ourselves in a mirror. I have been looking at this man from New Guinea for a long time and I think about his ability to see himself through the camera’s lens. Looking at photographs of people from the non-western world remains a much-debated political subject. I was a bit too young to be fully aware of the international world in the 1960s, but I did witness the profound role that media played in the national discussion during the American Civil Rights movement and in the light to end the war in Vietnam. I believe that part of Penn’s and the magazine’s idea of publishing these portraits of world citizens was an awareness that modern globalism had begun. For decades, the U.S. had generally been rather isolationist and Penn’s pictures from Morocco to New Guinea were a revelation to many Americans. Moreover, the photographs explored basic questions about the ethical role of the camera in our society. Those were fair questions to ask then, and today.

Thomas Persson: Penn’s ethnographic photographs started in Cuzco, Peru already in 1948…

Jeff L. Rosenheim: Yes, and I think that is the connection that he makes in his 1974 book Worlds in a Small Room. Such a lovely title. Worlds in a Small Room begins with Cuzco and continues through all the different end- of the year Vogue portrait projects. It ends with Morocco. Basically, it’s a metaphor. Worlds in a Small Room is the camera, the box, the ambulant studio. Penn had complete faith that if he could bring someone into his studio — in the city, or in a field tent — whether T.S. Eliot or the New Guinea man with the nose disc — something magical could happen. And it did. The photographs then would be about two people coming together, breathing the same air. From that connection, a picture would emerge out of that room, out of the box. I am interested in this idea that a fashion model from Paris, London, or New York is as elemental, clothed or unclothed, is just as revealed or still hidden, as this tribesman. I don’t believe he is more authentic than Lisa Fonssagrives wearing a Rochas mermaid dress, or less. I don’t rank them. The tribesman, like Lisa, is a participant in a wordless performance with Penn. He addresses the camera, and what he wears is just one part of the performance.

Thomas Persson: And through his choice of subjects he bridges that disconnect.

Thomas Persson is the editor in chief and creative director of Luncheon. Jeff L. Rosenheim is the Curator in Charge at the Metropolitan Museum, in New York.

Irving Penn : Centennial

April 24 to July 30, 2017

The Met, Gallery 199

1000 5th Ave

New York, NY 10028

USA