To mark the centenary of Irving Penn’s birth, The Metropolitan Museum of Art has open its doors in April to a major exhibition celebrating one of the foremost photographers of our time. With more than 200 prints on display (the majority a recent gift to the museum from The Irving Penn Foundation), the retrospective is the most substantial to date and explores every period in Penn’s prolific 70-year long career. From New York the exhibition will then travel internationally with a first stop at the Grand Palais in Paris in September.

The publication of the accompanying book Irving Penn: Centennial is an occasion in itself. Not only does it feature the largest selection of Penn photographs ever compiled, including works that have never been published, it also provides essays with a fresh intellectual understanding of the deeply private artist and the human being behind the masterful photographs. The book and exhibition are created and co-organized by Maria Morris Hambourg, who founded the Met’s Department of Photographs in 1992 and knew Penn personally, and Jeff L. Rosenheim, the department’s current Curator in Charge.

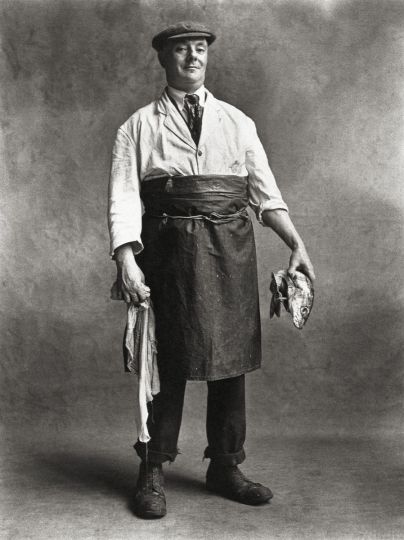

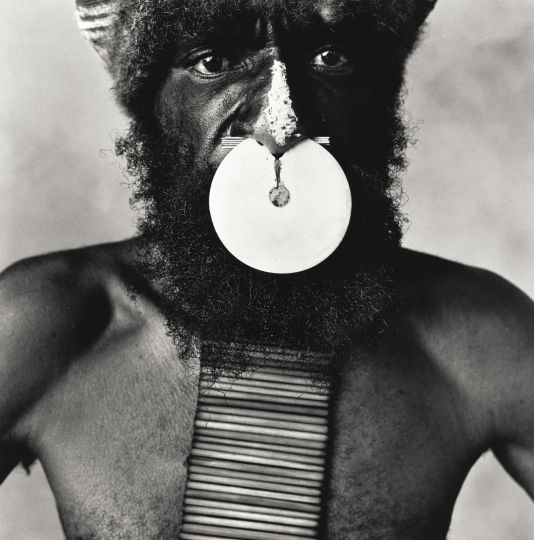

The two curators were asked to select three images each from the exhibition and reflect upon them with Luncheon magazine’s editor in chief and creative director Thomas Persson. The interviews here provide fascinating insight into the artistic creation and circumstances in which these photographs were made. From Marlene Dietrich to a tribesman in New Guinea; a female nude and a still life for Vogue; a fishmonger in London and two cigarette butts – Penn’s wide-ranging subjects were all part of his worldly narrative and, as they are observed within these pages, his profound talent for storytelling.

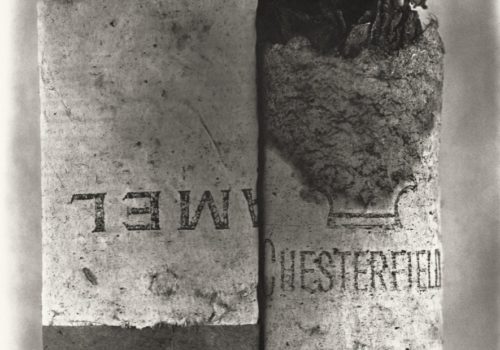

Today, we present the sixth and final part of this series with words on Cigarette No. 37, New York, 1972.

Thomas Persson: What was the critical reaction when the Cigarette series was shown at MoMA in 1975?

Maria Morris Hambourg: The critical reaction was surprise, boredom, and befuddlement. All the photographers, even those who had different styles, recognized Penn as the grand master and craftsman extraordinaire. No one was better at creating an image that was perfect in terms of its lighting, color, composition, and allure. As he was eminent at Vogue and preeminent in advertising, professional photographers expected to see some culmination of or selection from his usual genres. Other people saw only the subject matter and were horrified. Compared to actual cigarettes, the butts were hugely enlarged, so there were fourteen framed pictures in the room and nothing else. No relief, just one cigarette after another: “boring.” An assembly of crumbling and stained butts, the lowliest trash from the gutter, in exquisitely beautiful prints enshrined in the holy of holies, the Museum of Modern Art! Penn very smartly offered no clue as to what they meant. He said, “My delight in the material itself makes me seek out subject matter that will best take advantage of its possibilities.” In other words, it was art for art sake. And that appealed to the curator, John Szarkowski, because he loved the platinum printing, the muteness, the formal shape of these pictures. Penn had been mastering the process of printing platinum and palladium for the previous ten years in his private darkroom. He was trying to find a way to modulate the tonal quality in a print, to build it up in stages, as in etching or engraving. He also wanted to make prints that left room for the imagination, both that of the viewer and his own. (The printing of the Nudes in silver was the first major chapter of his investigation into how to do that.) He was also investigating how to move into something more tactile, a print in which the image would be couched in a thicker surface, have an almost dimensional quality, and more atmosphere. The results were his hand-applied platinums, which are so very different from a traditional black and white silver print. They are luscious, sensuous objects in themselves. To print the butts in this way was almost a contradiction in terms; it made them automatically ambiguous. Then there is the way he laid them out. At first they seem stark or blank, but then out of the carefully controlled presentation, the character of each cigarette begins to become apparent. Some of them dance, some soldier on, some weep.

Thomas Persson: Yes, they are so charming, almost like little human effigies…

Maria Morris Hambourg: Oh totally! Absolutely. Penn said, “Still life is a representation of people, as far as I’m concerned. Therefore, the people are in the background. The camera is simply not focused on them.” He studied the world for its evidence of hidden truths. A face or a stance reveals a life.

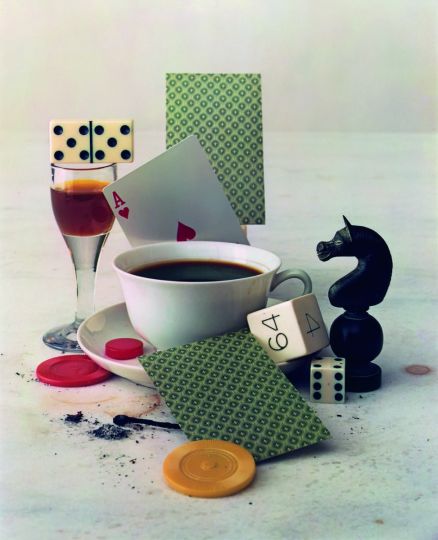

His early still life of a pair of liquor glasses and a couple of cigarettes, one stained with lipstick, is a portrait of a couple in conversation, after dinner. If you transpose this idea forward twenty years, you have Penn looking at these cigarettes the same way: These butts are evidence of lives, and surrogates for them — they sag, they stand at attention, they relate to one another, manifest resilience, exist in families, and so on. I met one of Penn’s assistants in Amsterdam recently who was involved with the Cigarettes. He took a collection box lined with soft paper and tweezers to pick up the butts and carefully nestle them into the box. Penn had instructed him to keep the butts intact, with the remainders of burnt tobacco, pavement grit or wayward pigeon feathers still in place. I asked him how Penn chose among the butts he brought back. He said, “Oh, Penn only wanted the ones with character.” Not the ones that were run over or stepped on? “No, no, the character had to remain intact,” he said.

Thomas Persson: It’s such an incredible idea to take something that no one looks at or cares for, such as cigarette butts, and elevate it to the highest of the highest within a photographic context. To treat something that anyone would consider worthless with such enormous dignity. I always thought there was almost something Buddhist about it.

Maria Morris Hambourg: I was just going to say the same thing. They are Zen. But at the time I don’t think anybody understood it.

Thomas Persson: In your book, Maria, you so brilliantly illuminate that the photographs were made in the ‘70s, which was a time of crime, corruption, and a generally low moment for New York City. It feels like Penn, with these cigarette pictures, put a mirror towards New York and even America itself.

Maria Morris Hambourg: Oh, I don’t think there is any question about it. I’ve always thought of those pictures as tombstones, for the city at that time, for Big Tobacco, and for those undone by smoking. Penn had made ads for Lucky Strike and Old Gold in the 1950s, but personally, he hated smoking. The cigarette lobby was incredibly strong and in control of the misinformation, but even before the Surgeon-General’s report came out (1964) and the relationship between cigarettes and disease became clear, Penn had forsworn further work for tobacco. I am sure he felt strongly about the issue. His father and his mentor, Alexey Brodovitch, both of them big smokers, had died of cancer, and New York City was awash in trash, crime was rampant, the cops were corrupt; it was a grisly moment. I moved to the city in 1971, and I remember well how seedy it was, with a flotsam of butts everywhere underfoot. It was a great city but in that moment, it was on its knees. The butts were small bits of the evidence; only Penn saw how they added up.

Thomas Persson is the editor in chief and creative director of Luncheon. Maria Morris Hambourg is the founding curator of the Department of Photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York.

Irving Penn : Centennial

April 24 to July 30, 2017

The Met, Gallery 199

1000 5th Ave

New York, NY 10028

USA