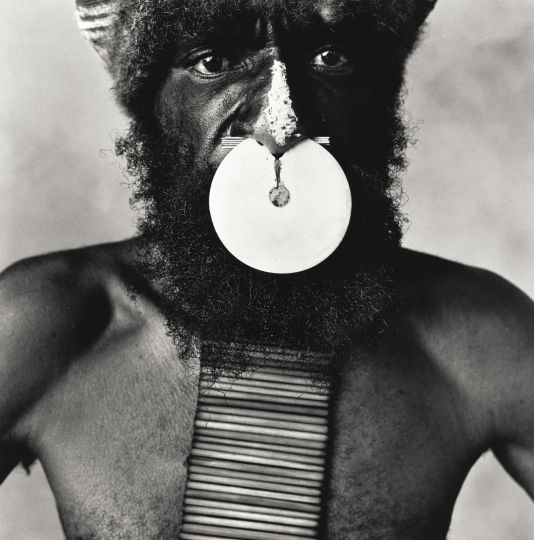

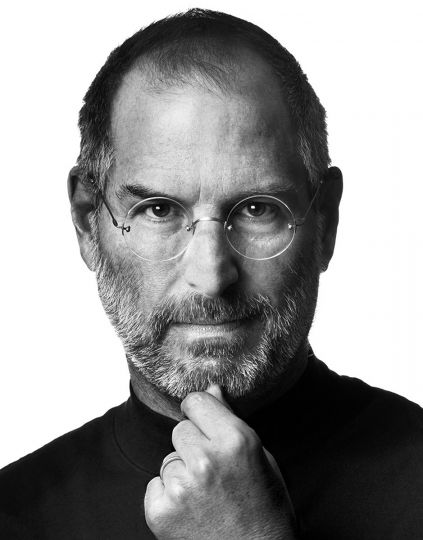

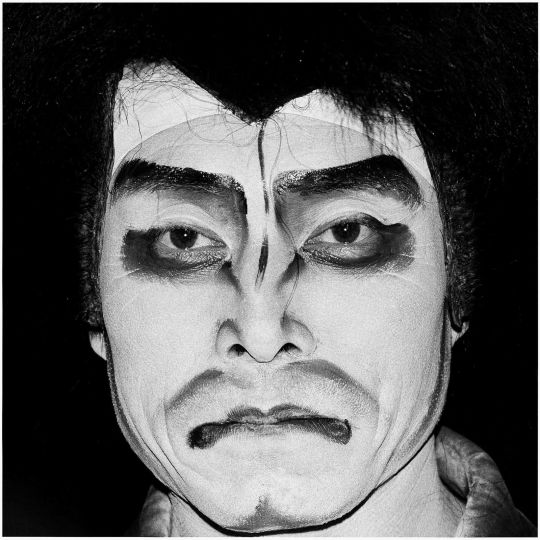

To mark the centenary of Irving Penn’s birth, The Metropolitan Museum of Art has open its doors in April to a major exhibition celebrating one of the foremost photographers of our time. With more than 200 prints on display (the majority a recent gift to the museum from The Irving Penn Foundation), the retrospective is the most substantial to date and explores every period in Penn’s prolific 70-year long career. From New York the exhibition will then travel internationally with a first stop at the Grand Palais in Paris in September.

The publication of the accompanying book Irving Penn: Centennial is an occasion in itself. Not only does it feature the largest selection of Penn photographs ever compiled, including works that have never been published, it also provides essays with a fresh intellectual understanding of the deeply private artist and the human being behind the masterful photographs. The book and exhibition are created and co-organized by Maria Morris Hambourg, who founded the Met’s Department of Photographs in 1992 and knew Penn personally, and Jeff L. Rosenheim, the department’s current Curator in Charge.