On May 6th Petapixel ran a story on Steve McCurry and images taken by him that were reportedly digitally manipulated. The story sparked a flurry of discourse on Facebook and other social media platforms about the appropriateness or otherwise of manipulating documentary images.

The Petapixel story followed a blog post by Italian photographer Paolo Viglione who had visited McCurry’s exhibition in Turin at the Venaria Reale. Viglione pointed out a Photoshop error in a street photograph taken in Cuba where a person has been repositioned. Others joined in on social media posting more supposedly manipulated images of McCurry’s, where people had been removed and a streetscape altered.

Comments ranged and raged. Some declared McCurry’s practice as utterly disgraceful and an affront to photojournalism. Others didn’t see an issue because the image in question was personal work, what McCurry described in his response to Petapixel as “art”. Yet McCurry, a member of Magnum Photos, is known as one of the world’s most celebrated photojournalists (although he now labels himself a ‘visual storyteller’ as stated in an article in TIME on 31 May 2016) and with that position comes an expectation that his images are the real deal.

Defining truth is a complex task. As photojournalist Peter van Agtmael, also a member of Magnum, pointed out in an opinion piece for TIME written in response to the McCurry incident, one person’s truth is different from another’s depending on cultural backgrounds, political persuasion and personal convictions. Yet within the frailties of human nature and the commercial imperatives of corporatized media, professional photojournalists are expected to uphold the journalistic tenets of their profession.

As stated in the NPPA Code of Ethics, a “visual journalist’s” role is to present a “faithful and comprehensive depiction of the subject at hand…to document society and to preserve its history through images”. News organizations and photo agencies have their own codes, which include strict standards that don’t allow the manipulation of images. Industry bodies such as World Press Photo are also doing their utmost to uphold the tenets of photojournalism putting stringent rules in place for the annual World Press Photo competition.

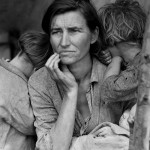

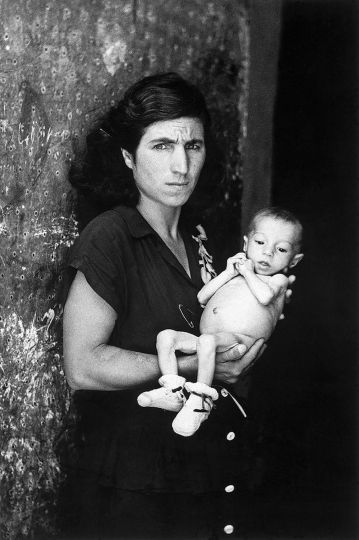

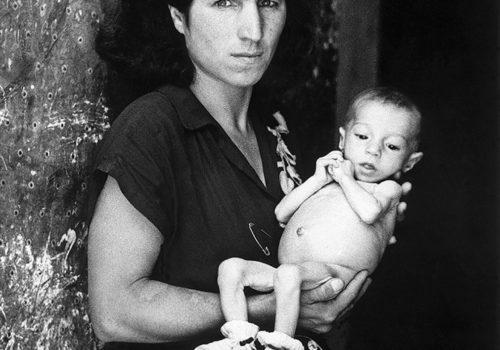

Manipulation of photographs has existed since the medium’s nascent years and even some of history’s most iconic images were the subject of tweaking in the darkroom. Dorothea Lange’s ‘Migrant Mother’ was altered in the darkroom to remove the mother’s thumb from the tent pole. According to James Curtis in his book Mind’s Eye, Mind’s Truth: FSA Photography Reconsidered the mother had reached out to grab the tent pole in order to steady herself and her grip on her baby. Lange removed the thumb, an act Curtis says was designed to show the mother as less capable of providing for her family and more as “someone stricken with anxiety”.

One could argue that because Lange’s ‘Migrant Mother’ was the result of a commission by the Farm Security Administration it isn’t strictly photojournalism, but this and other photographs taken at that time were used widely in the press. Is the manipulation of Lange’s image within the realms of what is considered allowable? Does it matter that this alteration may have shifted the narrative of the photograph to reflect what the commissioning body wanted? Does the fact that this photograph was part of a campaign to improve the working conditions of itinerant workers excuse the manipulation?

Whereas the audience of the 1930s had little knowledge of photographic processes, today audiences have greater awareness of the possibilities for manipulation of photographs, which impacts the public’s skepticism about the media’s ability to tell the truth. In fact in the US, the public’s faith in corporatized news is at an all time low with a recent Gallup survey revealing that only four out of ten Americans believe the media reports the “news fully, accurately and fairly”. In the annual trust barometer by Edelman “peer-influenced media…now represents two of the top three most-used sources of news and information” showing audiences are turning away from traditional news sources.

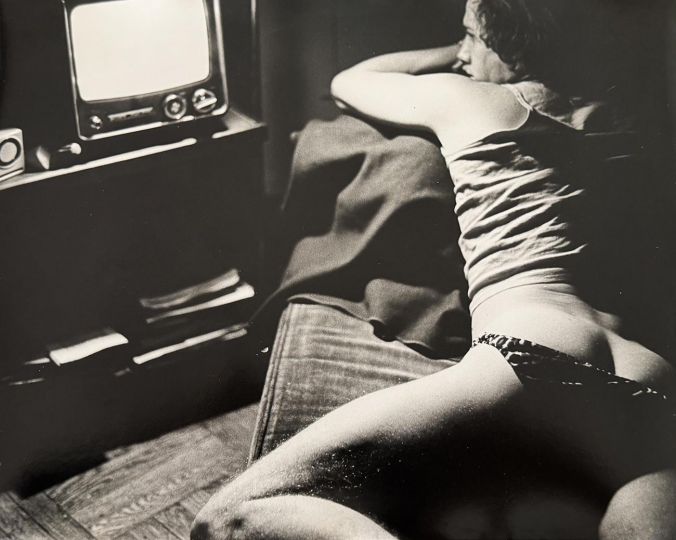

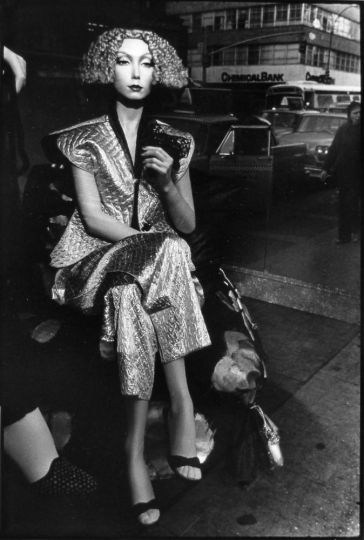

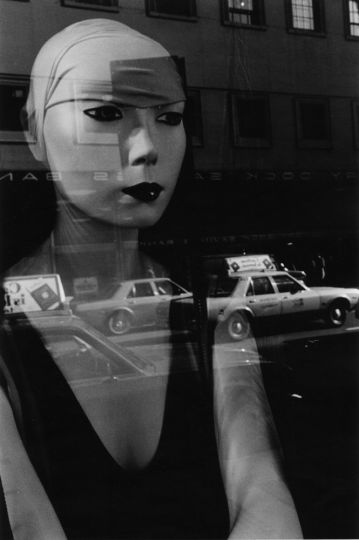

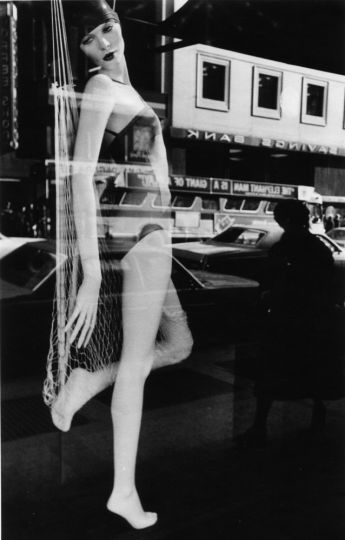

While we are living in a time when the photograph has never been more potent, a worrying, homogenized aesthetic is emerging in photojournalism where photographs like McCurry’s are looking more like stills from movies. Are the aesthetics of an image more important than capturing reality? Do we, as an industry and as the audience, want photographs that present a sanitized view of the world? Do we want future generations to look back at our visual history and be unable to define what was real and what was fabricated?

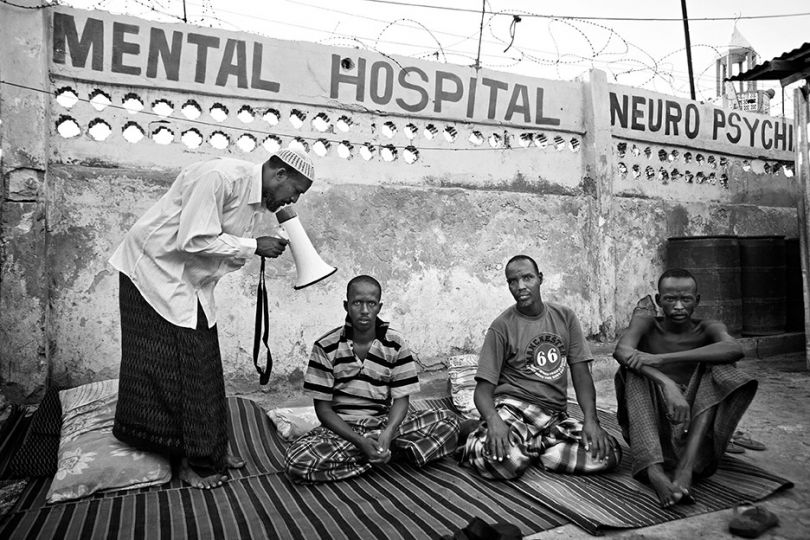

Photojournalists perform one of the most difficult, and at times thankless, jobs in media. Often they put their lives at risk to tell stories that are important and to give a voice to the voiceless. They play an essential role in documenting history, in telling meaningful stories and in helping us make sense of what’s happening around the globe and in our own backyards.

The world is not perfect, and photojournalism’s role is to reflect these imperfections. Photojournalism is the critical mirror of the world. In the past photojournalists have been confined to publishing their work through corporatized media, but now in the digital space there are new opportunities to engage with audiences directly. It is a transformative time. Photojournalists need to find new ways of storytelling and to redefine the way the world is documented. Let us hear your voice.

This article is part of a monthly series on photojournalism. Be part of the conversation. To share your ideas or thoughts on issues facing photojournalism email alison.stieven-taylor@monash.edu

Links:

Original post from Paolo Viglione http://www.paoloviglione.it/quando-steve-mccurry-etc-etc/

Petapixel http://petapixel.com/2016/05/06/botched-steve-mccurry-print-leads-photoshop-scandal/

Peter van Agtmael http://time.com/4326791/fact-truth-photography-steve-mccurry/

Photojournalism Now Blog – Photojournalism Now http://photojournalismnow.blogspot.com.au