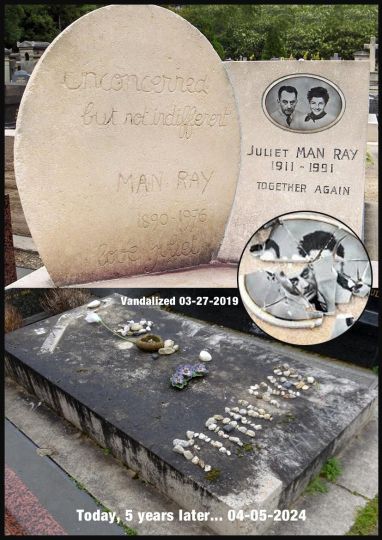

Man Ray (1890-1976) is an essential figure of the 20th century, inseparable from the history of photography, especially in this year 2024, when the surrealist movement celebrates its centenary.

In this context, Photo Elysée opens its doors to an exhibition presenting a selection of works from one of the largest private collections, never before shown in Europe. Led by Nathalie Herschdorfer, the museum’s director and exhibition curator, the curatorial focus is on the 1920s and 1930s, a pivotal period when photography asserted itself as an independent artistic medium. The exhibition “Man Ray: Liberating Photography” thus offers an opportunity to discover or rediscover the prolific, visionary, and enduring work of an artist who defined himself as a “fautographer.”

The scenography, designed by Swiss designer Adrien Rovero and graphic artist Camille Sauthier, immerses visitors in a reddish atmosphere before inviting them to explore an open space, allowing them to freely wander through Man Ray’s artistic abundance. However, this freedom can lead to some confusion, as the explanatory plaques are somewhat scattered throughout the exhibition. A guided tour is recommended to fully grasp the curatorial angle. The floor, dressed in a checkerboard pattern, unmistakably evokes the game of chess, one of the favorite pastimes of the artist and his accomplice, Marcel Duchamp.

In this regard, the exhibition begins by highlighting the significant role of Duchamp and Dadaism in awakening surrealism in Man Ray. The complicity between these two artists, pioneers of conceptual art, is revealed through an emblematic work: Belle Haleine: Eau de Voilette by Marcel Duchamp (1921). Duchamp created a ready-made by incorporating one of the first portraits of Rrose Sélavy, his alter ego, onto a perfume bottle. Man Ray then photographed this object, sealing their collaboration. Through this subversive act, Man Ray claimed photography as an independent art form.

Leaving New York for Paris, he quickly established himself as the photographer of the Parisian intellectual and artistic elite. The exhibition presents a multitude of portraits, including major figures of the surrealist movement such as Louis Aragon, André Breton, Antonin Artaud, Tristan Tzara, Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, Dora Maar, and many others. Some prints also illustrate his pioneering collaborations with prestigious fashion magazines, notably Vogue, where Man Ray was among the first photographers hired at a time when these publications were transitioning from drawings to photography to present fashion collections. These commissions constituted his main source of livelihood.

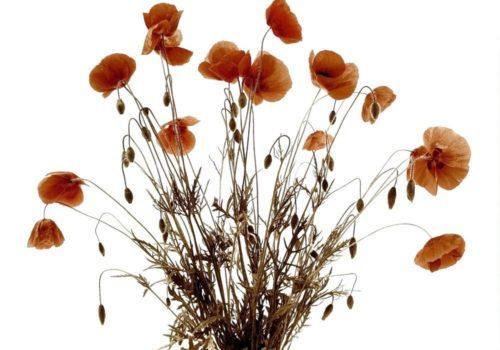

The visit continues by unveiling a more personal dimension, revealing the surrealistic contours of Man Ray’s work. Apart from his commissions, he was fascinated by photographic accidents and liked to ironically define himself as a “fautographer”; “when I was in the darkroom, I deliberately avoided all the rules, mixed the most absurd chemicals, used expired films, did the worst things against chemistry and photography.” He excelled in the art of subverting photographic conventions by freely exploring the medium, which led to the discovery of solarization (formerly called the Sabatier effect) and the photogram, which he renamed “rayograph.” These reconsidered photographic processes greatly contributed to his enduring fame.

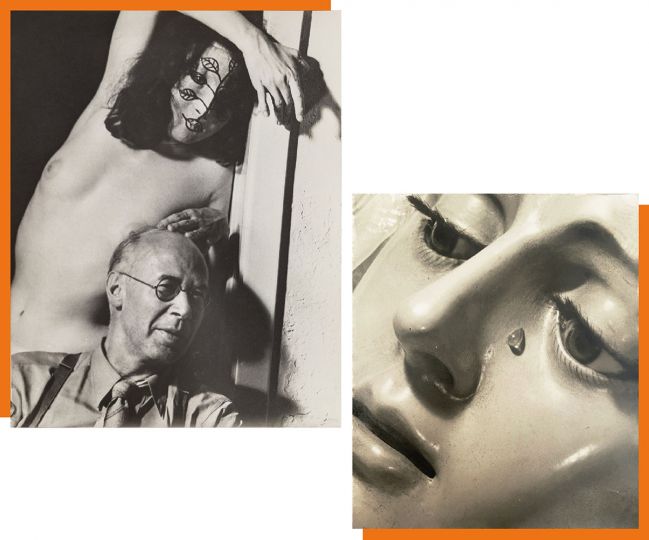

The female body was Man Ray’s primary source of inspiration, which he used to serve the surrealist aesthetic. This exhibition reveals the artist’s major muses, such as Kiki de Montparnasse, Meret Oppenheim, Adrienne Fidelin, and Lee Miller, who was both a photographer and Man Ray’s lover and collaborator. She is notably present through one of her “solarized” portraits. It is crucial to highlight her role in the (re)discovery of solarization; an accident she caused in the laboratory initially revealed this technique, which Man Ray then perfected. In a letter to her brother, she recounts: “Something brushed against my leg… I screamed and suddenly turned on the light. I did not find what it was, maybe a mouse. But I realized that the film had been exposed. In the developer tray, there was a dozen developed negatives of a nude on a black background. Man Ray grabbed them, plunged them into the hypo tray, and looked. The unexposed part of the negative—the black background—had been altered by the lamp light up to the edge of the white nude body.”

After the war, Man Ray continued to rework his photographs from the 1920s and 1930s. From his old negatives, he developed new prints, adjusting the framing to focus on a detail, such as the eye with glass tears in his famous work, Les Larmes (1932). These late experiments led to “late” prints, a specificity of Man Ray that Nathalie Herschdorfer wanted to highlight.

Moreover, visitors can discover all of Man Ray’s films, including EMAK BAKIA (1926). This improvised film is described as a “cinepoem,” a constellation of technical and iconographic experiments, testifying to the artist’s polymorphic genius.

Written by Maeva Dubrez.