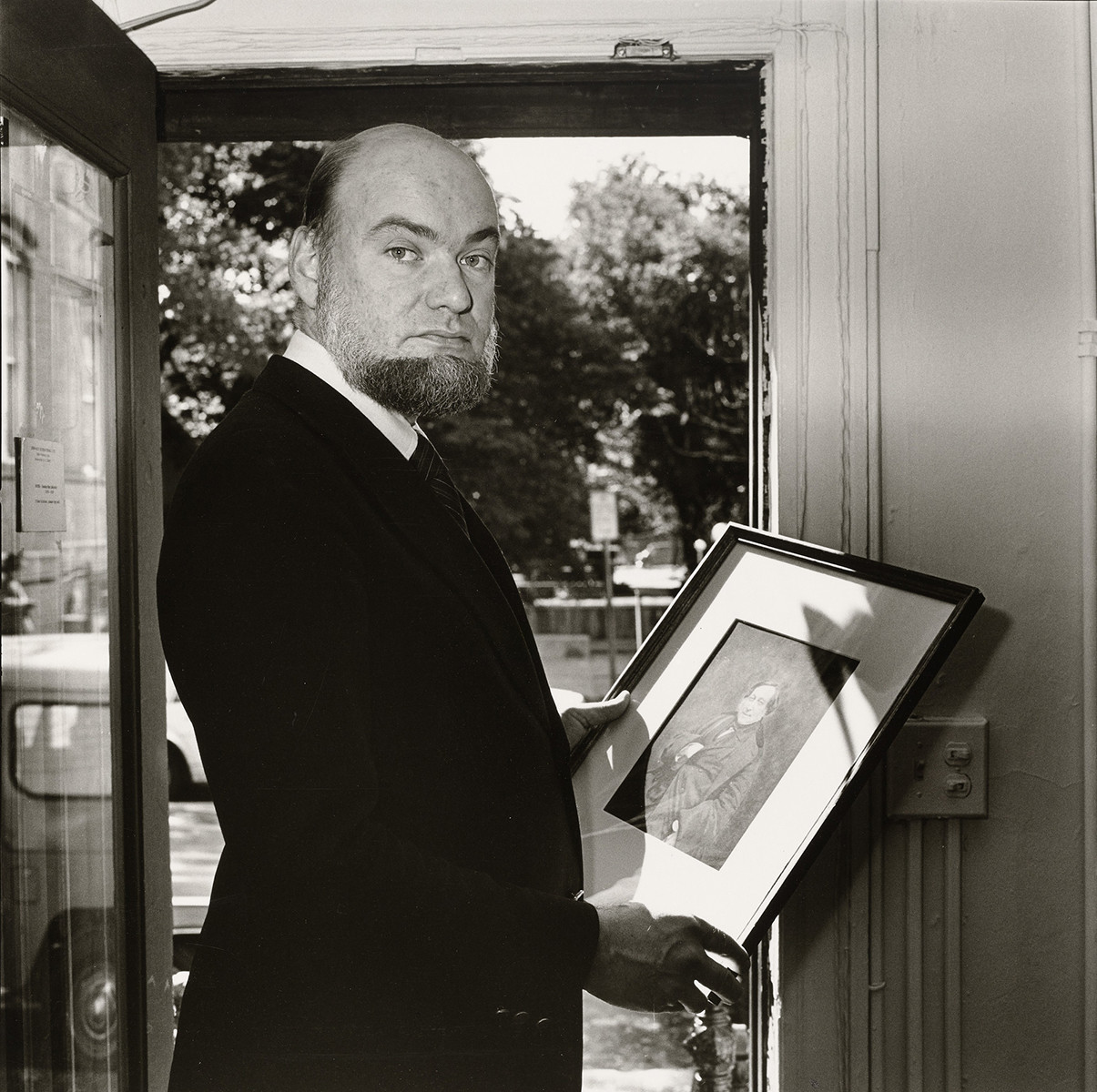

A few days ago, Harry Lunn would have celebrated his 78th birthday. For many people, his flamboyance, his knowledge of photography, his generosity, his excesses and his mood swings are missing. New York art dealer Peter Hay Halpert is one of those people.

Harry H. Lunn JR

29 April 1933 – 20 August 1998

The recent anniversary of Harry Lunn’s birthday presents an occasion to assess his seminal role in the creation of the modern photography market. Lunn was the dean of photography dealers and one of the pioneering figures in the photography community over the latter half of the 20th century. His name is no longer spoken of by the current crop of collectors who populate the auction houses and museum acquisition committees, but in his time he was a larger-than-life personality who was primarily responsible for creating the marketplace as it exists today.

Lunn was born in Detroit and in 1954 received his degree in economics, with honours, from the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, where he was the Editor-In-Chief of the college newspaper, The Michigan Daily. During his senior year he was recruited by the CIA. He became involved in the National Students Association, and in 1965 became director of the Foundation for Youth and Student Affairs. However, in 1967, an article in Ramparts magazine revealed the organisations’s ties to the agency, effectively blowing his cover. Lunn, who had also served at the Pentagon and the U.S. Embassy in Paris, found he no longer had a career as an intelligence officer; he briefly sold Capitol Hill real estate in Washington, D.C. before he found his true vocation.

In 1968, he opened his first gallery on Capitol Hill before moving, first to Georgetown and eventually to 406 Seventh St. NW in Washington. His initial operations, Graphics International, specialised in original French etchings and lithographs of the 19th and 20th centuries, drawing on his experience dealing privately in prints while he was stationed in Paris. By 1970 – 71, though, he was focusing on photography, at a time when there was virtually no market whatsoever for fine art photography. Margarett Loke, writing in the New York Times, notes that “During the first two decades of this century, Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery 291 was much more a showcase for modern art than it was a photography gallery. In the 1930’s and 40’s, Julien Levy showed photographs at his New York gallery, but there was no market for them. In the 1950’s, Helen Gee’s Greenwich Village coffee-house, Limelight, had a photographic gallery at the back. But even when pictures were about $15 each, only a few sold. When Mr. Lunn became interested in photography, only one gallery in the United States – opened by Lee Witkin in Manhattan in 1969 – was devoted to the medium.”

Ansel Adams served as Lunn’s introduction to photography. He recalled that when he first saw Adams’s “Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico,” he thought “This was an extraordinarily graphic, marvellous image. As a dealer in prints, I could very much relate to it. I didn’t even know who Ansel Adams was.” In January 1971, Lunn exhibited Adams’s prints, priced at $150. The show proved to be a harbinger of things to come for Lunn, with sales totalling $10,000. The current record price for an Ansel Adams photograph, achieved in 2010 during the sale of photographs from the Polaroid Collection, is $722,500. Perhaps no measure better demonstrates the phenomenal growth of the photography market than a comparison of the prices for Adams’ work since Lunn began making a market for his pictures. He followed up that success with a museum-quality exhibit of photographs and rayographs by Man Ray. In 1972, when Sotheby’s in London held their first major photography auction, Lunn’s acquisitions amounted to a quarter of the value of all the pieces sold.

Lunn always had a gambler’s instincts and he bet on artists like a player at the roulette wheel. He acquired a collection of 5,500 Lewis Hine photographs in 1973 – 74, and followed that up a year later by purchasing the Walker Evans Archive of 5,500 prints, many of which were vintage. In conjunction with the Marlborough Gallery, he bought the archive of Eugene Atget images printed by Berenice Abbott, as well as Abbott’s inventory of her own photographs. When Adams announced that he would not print up any of his classic images after 1975, Lunn ordered over 1,000 prints in bulk, paying an average of $300. He purchased 1,600 prints by Robert Frank in 1977, and in 1978 arranged with Marlborough to take on exclusive representation of Brassai. During this period, he also represented the Diane Arbus Estate, and bought hundreds of photographs from the estate of Heinrich Kuhn. In essence, he was making a market, where none had existed, and he was doing it with a great eye.

Lunn’s vision extended beyond seeing value in a medium that other art dealers had ignored. He recognised the need to develop a broad market for photography and he became the medium’s great champion. He encouraged others to set up galleries and consigned freely from his inventory. Jeffrey Fraenkel, one of the premier dealers in the field today, remembers that “Harry was so important, influential and integral to me getting my gallery off the ground. He took a chance and consigned work by Arbus, Frank and Evans that was crucial to the gallery’s early years.” Robert Mann, who now runs his own gallery in New York, started working for Lunn in 1977 and stayed with him for seven years. “He was the Great Facilitator,” says Mann. “I was able to witness the birth of an industry, so much of which was choreographed by him. Nothing gave him more pleasure than helping people, and knowing he had that power to do it. When I opened my own business in 1985, he always kept in touch and stayed close. He was one of the most generous people I ever met.” The number of dealers, curators and collectors who associate their introduction to photography with Lunn is staggering. Peter Galassi, head of the photography department at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, once worked for Lunn. Maria Morris Hambourg, chief curator of photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art told the Washington Post that “Harry was the original source. In one way or another, he influenced virtually everything that happened in the photography world during the last quarter of this century. More than any other single person, he made the market and fed the appetite for fine photographs.”

His imprint can be seen today in many of the most important collections. He was one of the first experts on 19th century French photography and organised the “catalogue raisonne” of Louis de Clercq. Of the ten known sets of de Clercq’s monumental survey of Syria, Egypt, Jerusalem and Spain, Lunn sold one complete set to the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), another to the Gilman Collection, and broke up two others to sell to individual collectors. Richard Pare, at that time Curator of the CCA collection recalls that “Harry was central to our work and efforts. Those days were unbelievable. Work by many different 19th century photographers was coming onto the market for the first time, and we probably bought more from Harry Lunn than any other dealer.” Sam Wagstaff, whose collection is now one of the cornerstones of the Getty Museum’s photography department, bought regularly from Lunn as did Harvey Shipley Miller, a major Philadelphia-based collector who now sits on numerous museum boards and committees. When Manfred Heiting published the first volume of his collection, he acknowledged Lunn “For his bold vision and grace. For being the Godfather of many and much in the field. For sharing knowledge and friendship with me. For guidance in building my 19th century collection.”

He broke a path where few thought a trail could exist. As an expert on 19th century French photography, Lunn frequently organised auctions at the Hotel Drouot in Paris. He was one of the founding members, in 1978, of the Association of International Photography Art Dealers (AIPAD). When he spoke to the group that year about “the creation of rarity,” there were only 30 or so members; today there are almost 150. He was the first photography dealer to become a member of the Art Dealer’s Association of America, and initially was one of only three dealers who specialised exclusively in photography to exhibit at the organisation’s Art Show held each year at the Armory in New York. It is indicative of his prescience, though, that now, most contemporary galleries at the art fairs regularly display photographic- based work. Mathew Marks, one of the premier contemporary art dealers, once commented that today no collector intent on building an important collection of contemporary art could afford to ignore photographic work: “Otherwise, they’re building a collection of painting and sculpture, but that doesn’t mean it’s a comprehensive contemporary art collection.” Lunn was also the first to present photographs at the Basel Art Fair, and he was the eminence grise behind the Paris Photo fair, held at the Carrousel du Louvre. He viewed the event, which opened with 55 dealers, as “a way to raise photography’s profile.” Today, the fair has trebled in size.

Mann notes that “Right from the beginning, Harry had a very broad palette.” While he handled great masterpieces of 19th century photography, he was equally at home with cutting edge contemporary work. He was an early advocate for Andres Serrano, Pierre et Giles, McDermott & McGough, and Joel Peter Witkin. In 1981 he exhibited Robert Mapplethorpe’s work and, with the Robert Miller Gallery in New York, published the artist’s infamous X, Y, and Z Portfolios. “Harry didn’t limit himself,” says Mann. “His own tastes ran the gamut.”

Lunn’s accomplishments were surpassed only by the grand manner in which he conducted his affairs. His double-breasted blue blazer was a stylish hallmark at auctions that, initially, were decidedly low budget affairs. His booths at art fairs were decorated with furniture by Hoffman and Frank Lloyd Wright and oriental rugs, and he framed and displayed photographs with a dramatic flair that emphasised their value at a time when few besides he appreciated it. He was a gourmand who favoured fine Meursaults and Tanqueray gin. An avid bridge player, he took a messianic approach to organising games at which he generously tolerated partners whose enthusiasm flagged long before his own had cooled. He entertained from his suite at the Westbury Hotel in London when attending the auctions there, and was a regular at the gaming tables at Aspinalls as well as at Deauville. Margaret Weston, of the Weston Gallery in Carmel, California, called him “The Lion King.” With his booming voice, beard, bald pate and imperial demeanour, he fit the description. He was a complex, complicated man, who seemed troubled in later years even as the market he created reached new heights. He closed his Washington gallery in 1983 and operated as a private dealer with bases in New York and Paris. Charles Isaacs, an influential private dealer, says that “It became a crushing mantle. But Harry wore his heart on his sleeve. He really wanted people to love the things he loved.”

These days, it is harder to find the traces of Lunn’s influence. Many of the great photographs he handled have moved on to other dealers, other collections. In some cases, the backs of prints may bear his gallery stamp, but for the most part, their provenance is hard to determine, or even lost. It is becoming increasingly difficult to discern the handprints of many who championed photography in the 60s and 70s, when the modern photography market was being developed. Exhibitions featuring work from museum collections show only that the work came from the Getty, for instance, but do not denote which pieces came from Sam Wagstaff’s collection and which from Arnold Crane’s. It is even rarer to be able to appreciate the role a great dealer in building those collections.

A recent drama by Simon Gray, titled The Old Masters, deals with the lives of the renowned art critic and consultant, Bernard Berenson, and the legendary art dealer, Joseph Duveen. The painting masterpieces that these two men handled are testament to the significant role each played in the art market of their era. In his times, Harry Lunn was the Duveen of the photography market. The play has yet to be written, though.

Peter Hay Halpert