In the late 1980s the Historic Houses Trust rescued four tonnes of forensic crime negatives from a flooded warehouse in Lidcombe and relocated them to Sydney’s Justice & Police Museum. Fifteen years on, the Historic Houses Trust has reproduced to stunning effect a selection of more than 200 photographs from this extraordinary archive, casting a fascinating light on the shadowy underworld of inner Sydney in the years between the two world wars.

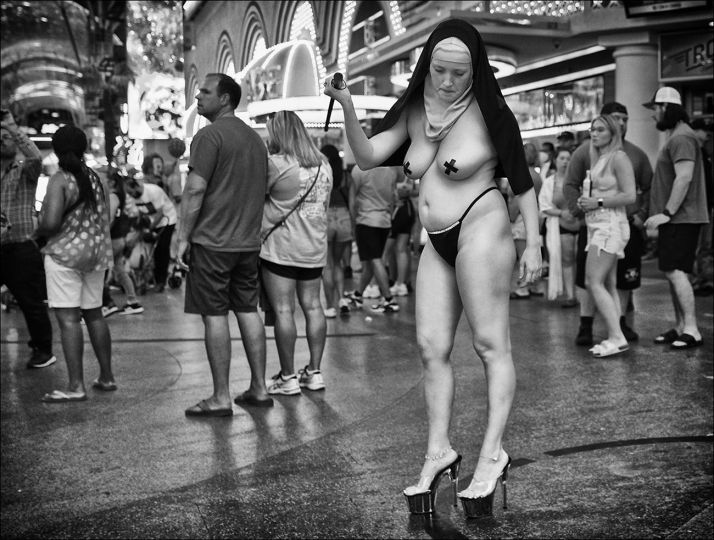

Author Peter Doyle spent three years in the cavernous loft of the Justice & Police Museum sifting through the hundreds of thousands of images in this chaotic, undocumented archive, selecting images and uncovering the stories which lie behind them. Here he delighted in the dark streets, the back alleys, grimy corner shops, pubs and factories as well as the kitchens, parlours and bedrooms where crimes and accidents occurred. Doyle also encountered the people of this world – the thieves, breakers, receivers, users, gingerers, hotel barbers, shoplifters, dope users, prostitutes and the occasional murderer, through an astonishing array of mugshots of men, women and children who found themselves involved as perpetrators, victims or simply as bystanders.

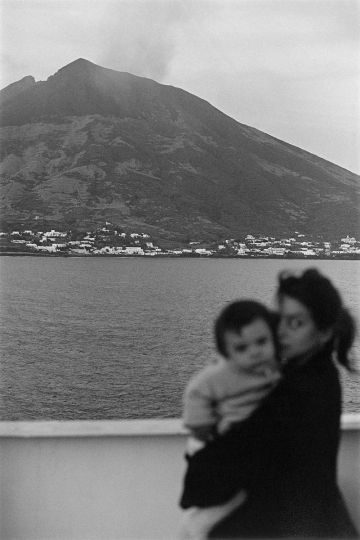

‘By cross checking names and dates with police records and newspapers of the day we have been able to piece together many of the stories behind the photographs, but in most cases we have no name and no date – no information other than what is suggested by the image itself. Each photograph offers an intimate, raw and often hauntingly beautiful record of the mysterious people and dark places of both a lost Sydney as well as a Sydney we can still recognise today,’ says Peter Doyle.

The forensic eye: photography’s dark mirror:

The forensic photograph is a fragment scissored from time; a powerful form of evidence and an official document, but one that is authored by an individual and therefore marked by a personal vision. Every crime scene photograph is also a form of intrusion on private pain, justified because the detective will use it later to arrive at the truth of what happened. Caleb Williams discusses the importance of the archive, the role of the crime scene photographer, the forensic process, the forensic aesthetic as well as the recent popularity of the crime scene investigator (CSI) in today’s popular culture.

Gathering evidence:

Most of the early police photographs were taken within a few miles of the Criminal Investigation Branch in Central Street in the city. In many cases we have little idea why the photograph was taken. A great number of the scenes, however, are recognisable as the streets of Surry Hills, Darlinghurst, Redfern, Paddington, Broadway, Chippendale, Glebe and waterfront areas. In the days when these photographs were taken, the details of home life were not generally discussed in public, rarely written about, and depicted – if at all – only in the most idealised ways. The front door of the domestic dwelling presented an almost total barrier between the public life of the street and the private life of the home. Many of the photographs show cramped, grimy interiors of rooming houses and flats. Greasy surfaces, unswept floors, bare walls, and empty bottles on tables and bedroom dressers all suggest transient, borderline lives. Other photographs, however, reveal well-kept interiors, crowded with neatly ordered furniture, bric-a-brac and framed pictures.

Persons of interest:

During the years 1912–1930 Sydney police photographed around 2,500 actual and suspected criminals, or ‘persons of interest’. Over 1,000 of those portraits have been uncovered during research into the police archive. Most were taken in the cells at Central Police Station. Originating from countless routine police investigations, the images focus on the thousands of men, women and children who found themselves involved as perpetrators, victims or simply as bystanders. Included in the collection are mug shots where we encounter the people of this world – the thieves, breakers, receivers, users, gingerers, hotel barbers, shoplifters, dope users, prostitutes and the occasional murderer. We do not know what criteria were used in deciding who was photographed. A number of the subjects are not found in police records at all – in some cases it appears they were simply unlucky enough to be found in the company of a suspect. Others were charged with relatively minor offences.

Spirits awake: encountering the archive:

‘And I have often felt a charged communication when an 80-year old mug shot retrieved from a dusty box materialises on the screen once the scanning software has worked its magical resurrection.’ Caleb Williams discusses the notion of ‘discovery narrative’ and the responsibility to research, interpret and exhibit rescued collections of visually significant and historically illuminating material.

(Press release)

City of Shadows, Sydney Police Photographs 1912 – 1948, Peter Doyle, Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, 2007