The highlight of the public programme at Paris Photo this year is an exhibition of works by one of the most important and certainly most individual American photographers of the postwar era, Larry Fink (1941 – 2023). Sensual Empathy as it’s titled, is curated by Lucy Sante and presented by MUUS Collection.

MUUS Collection acquired the Larry Fink estate earlier in the year and the team is still in the very early stages of getting to grips with all its contents, as founder and owner Michael W. Sonnenfeldt explained: “Larry Fink kept his vast archive in various locations on his farm in Martins Creek in Pennsylvania. We are dealing with an enormous amount of material. To give you an idea of the size, it took three 30 feet trucks to pick up all the boxes.”

MUUS Collection will be familiar to the Paris Photo audience by now. It presented its first exhibition at the fair in 2021, Deborah Turbeville: Passport, with unearthed works from the estate. It was followed in 2022 by an exhibition of early work by Rosalind Fox Solomon, and last year, MUUS Collection showed a selection of Fred W. McDarrah’s images of the struggle for LBGTQ+ rights, starting with the Stonewall Inn Uprising in New York in 1969. Elsewhere, it presents exhibitions at AIPAD’s The Photography Show, as well as museums and galleries around the world.

The story of the MUUS Collection is fascinating, as my conversation with Michael W. Sonnenfeldt reveals. Later on, I spoke to Richard Grosbard about his contributions to the collection.

Sonnenfeldt describes MUUS Collection’s modus operandi as “truly unique”. It is. In the last few years, the collection has exclusively focused on acquiring estates and whole archives, exactly what most museums and collections shy away from, as they require space, investment, and above all, real commitment.

Outside the world of photography, Michael W. Sonnenfeldt has had a long career as an entrepreneur, investor, and philanthropist. In the last 25 years he has been involved in numerous non-profit organizations focused on the environment and climate change, national security, Middle East peace, international peacekeeping, and the US/UN relationship.

MUUS Collection was officially founded in 2013. It had just opened its own facility in Tenafly. But the story of Sonnefeldt’s involvement with photography begins much earlier. While a student at MIT studying for his bachelor’s degree, he took a course with photographer Melissa Shook, an experience that would have a profound influence on his way of looking at photography. Later on, when his son was at Princeton University, Sonnenfeldt acted as a photographer for his sports team.

In 1989, he acquired an important album with images of Jerusalem, taken by the Scottish photographer James Graham between 1853 and 1857, which he donated to the Israel Museum in 2005. It marked the genesis of Sonnenfeldt acquiring pivotal moments in history captured by photography.

In 2008, he began acquiring large portfolios, soon followed by whole estates. I asked Sonnenfeldt if he in those early years had a clear idea of how he wanted MUUS Collection to collect American archives.

Michael W. Sonnenfeldt : Absolutely not! It was a passion that turned into an insight. Whenever we made an acquisition, it felt like we were tapping into a unique opportunity, discovering a gold vein. At that early stage, we had no way of knowing what it even meant to take on an estate. It’s taken us a decade to get a proper sense of how complex it is. The more complex an estate is, the more it meets our mission. We have the fortitude, and frankly, the excitement it takes to work with these estates.

Before you started acquiring estates, you were acquiring portfolios.

MWS: Sometimes, an artist looks to a collector to help support him or her and might sell 100 pictures or 1000 pictures for whatever reason. What we realised as we were collecting these portfolios, was that they still weren’t giving a picture of an entire lifetime career. There’s very little serendipity in a portfolio because an artist takes bodies of work and then extracts from them. You get a selection. That’s very different from acquiring a whole estate, as we just did with Larry Fink. Many of those boxes might not have been opened in 10, 20 or 30 years, and it will take years for us to assess what it all is.

Museums and other institutions find whole archives problematic. They require a lot of storage space, conservation and research.

MWS: It’s a daunting task, and very few collections, either private or institutional, have the capacity or the will to take on projects like these. We have a large staff, a big facility, the resources and the long-term perspective, which you need to take on an estate. When we acquire an estate, it takes five to 10 years to reveal, review, digitise, catalogue, research, and present work within it that current audiences don’t know about, or in many cases, no audience knows about. The artist might have worked on body of work but never had a chance to show it to the public. Having access to an entire estate gives scholars access to a body of work that they wouldn’t otherwise have. The legacies of the most famous photographers, like Richard Avedon, are ensured through foundations, but there are so many other great photographers that have not gotten their dues. When they start thinking about their legacies, they find that there are no homes for the entire archives. Many estates get broken up or unfortunately, thrown away. If an institution accepts them, the material is often filed in boxes, put in storage somewhere, and forgotten, possibly never to be seen again.

Taking on a whole estate signals a wish to explore a photographer’s work in depth.

MWS: One of our most famous pictures is Alfred Wertheimer’s 1956 Elvis Presley image The Kiss. There is a lot to be learnt from that one picture but Wertheimer made roughly 10 photographs of that moment and the sequence shows the artist’s working methods and the process of choosing the final image. You could write a dissertation on chosen photographs, but you can’t even begin the research until you have seen the whole series. It’s only when you have an estate that you can make that kind of critical analysis that academics love to make when they come to our facility to look at an artist’s work.

Acquiring whole estates is different from buying a large group of prints.

MWS: A typical acquisition can take a year to two years to negotiate. There’s a very difficult transition that goes on with a photographer’s heirs, about what to do with the legacy of their mother, father, husband, wife or friend. The sellers are caught between wanting to do what’s best for the legacy of their loved one and not knowing what to do with it. To them, it might feel like every piece of work is a piece of gold but that’s not the way it works. We have walked away from negotiating estates several times. Something is only worth what a buyer can afford to pay or is willing to pay and what a seller is willing to sell for. Sometimes, the gap is just too big. Because we’re a collection, people make all sorts of assumptions about our resources and what we can afford. We have to buy at a price that allows us to invest a significant amount of money in the scholarship, the resources, the research, the shows, the documentaries and the books that we do. It’s very challenging to do all those things but we’re privileged to have the resources to underwrite it all. The most important part of what we do is that we take as seriously as possible the trust that’s invested in us by taking on an entire life’s work of an artist.

You focus exclusively on estates of American photographers. As the profile of MUUS Collection has grown, are you now increasingly contacted by photographers or their heirs looking for a permanent home for their estates?

MWS: We are! I think maybe the proudest of our accomplishments is that we now have children, heirs, and spouses of some major fantastic photographers come to us and say, “You must acquire my mother’s, father’s, sister’s, brother’s estate!”, because they’ve seen what we’ve done with Deborah Turbeville and the other estates. Having said that, we can only acquire an estate every two or three years because we are looking far and wide to create a cohesive stable of artists, and we have space and staff considerations.

MUUS Collection doesn’t have its own exhibition space. Instead, you have opted to collaborate with fairs and museums around the world. It seems to have worked out very well for you.

MWS: It has. We started at Paris Photo in 2021, and then we built a presence at AIPAD’s The Photography Show, and we show exhibitions in museums around the globe. This year, there are 12 travelling shows, including the Deborah Turbeville: Photocollage show that started at Photo Elysée in Lausanne, travelled to Huis Marseille and just opened at the beginning of October at The Photographers’ Gallery in London. MUUS Collection exists within an ecosystem of great photography museums and fairs. We want to work with museums, support them and absorb their expertise. To make the work available to a new public, we realise how important these collaborations have been for us and our partners.

Can you tell me about the facility in Tenafly and the size of the collection?

MWS: The size of the facility is about 5000 feet, and we have some additional storage space. It’s of the same standard as any first-class institutional archive in the world, with temperature control, fire suppression, storage and data retrieval. Before the arrival of the Larry Fink estate, we had just over 500,000 works in the collection. Right now, we are expanding the facility to incorporate Larry’s archive and we are having to build additional racking with temperature control systems. While we don’t have a public exhibition space, we do have a beautiful showroom that can accommodate a dozen people at a time, may they be researchers, curators or other visitors. We have a wonderful team of 8 people, two of whom are based in Europe.

The first time you exhibited at Paris Photo was in 2021 when you showed the Deborah Turbeville exhibition Passport. People travelled from all over the world just to see it. The exhibitions you have shown elsewhere of her work have also been packed. Were you surprised by the reactions?

MWS: The Deborah Turbeville estate was acquired after Richard Grosbard joined us in 2020. We were collecting some very interesting things before Richard arrived, but I didn’t have the eye that Richard brought to my vision. When he went to see the Deborah Turbeville archive, he came back thoroughly excited about it. I might have not fully understood it at the time, as I was thinking about a different part of our process. Richard was absolutely right about the archive and it has worked out really well. We have just published a book of her Mexican work in collaboration with Louis Vuitton. If you own the whole archive, the Mexican work might seem like a footnote, but with a new lens, all of a sudden there’s a fantastic book. Turbeville has a unique place within our collection as she lived both in the world of reality and the world of fantasy, in a way that is different than any of our other artists.

After my conversation with Sonnenfeldt, I spoke to Richard Grosbard, Advisor to MUUS Collection, and Consulting Director of the Deborah Turbeville Archive. Grosbard has been a collector of masterworks of photography for 50 years. Because of his long friendship with Rosalind Fox Solomon, Grosbard was able to acquire her collection for MUUS; similarly, it was Grosbard who took the first important steps in the process that led to the acquisition of the Larry Fink estate. I asked him how it all came about.

Richard Grosbard: The first time I met Larry Fink was in November 2022. I had been introduced to him by Cologne-based gallerist Julian Sander. I went to see Larry and his wife Martha Posner at their farm in Martins Creek. Larry kept his amazing archive in a number of locations on the property, in studios and barns. It was absolutely daunting to see the sheer quantity of material and to see just how amazing it all was. Afterwards, I spoke to Michael and told him that the collection was definitely something we should acquire. We entered into negotiations with Larry and Martha but then Larry became very ill in 2023 and sadly passed away on November 25th of that year.

We were very cognisant of Martha’s grief and wanted to give her time to think about what she wanted to do with the archive. I then worked with Martha for the next six months trying to find a way to come together with MUUS Collection. There were a lot of issues to resolve, including some publications and exhibitions that were in the works. Martha told me that Larry had wanted his archive to go to MUUS Collection, so she really wanted to make it happen. With Michael’s negotiation skills, we were able to come together in June of this year.

What is the focus of the exhibition at Paris Photo?

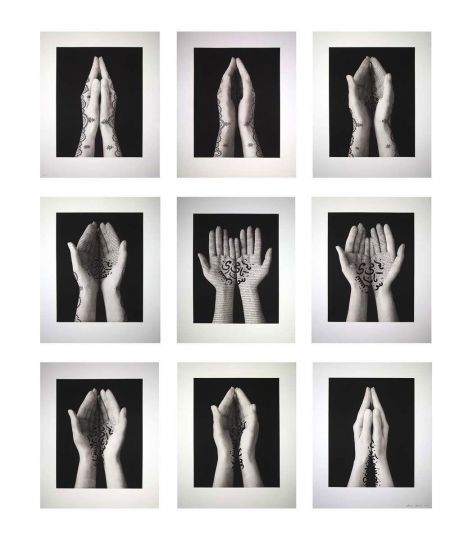

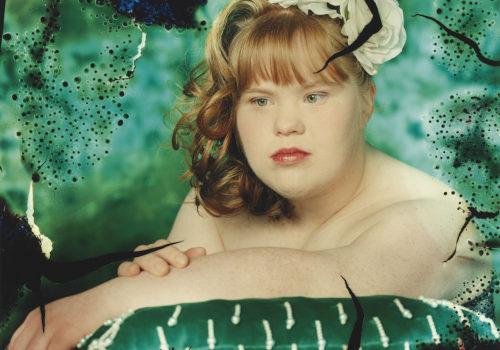

RG: The exhibition is called Sensual Empathy, the two words that Larry often used to describe his own work. It’s curated by Lucy Sante. She and Larry were great friends. They both taught at Bard College for many years. Lucy was enamoured with Larry’s work, and they developed a very strong relationship. The exhibition comes out of the book that Powerhouse is publishing, Larry Fink: Hands On/A Passionate Life of Looking. Lucy decided to focus on the prevalent themes of Larry’s work. The centrepiece of the exhibition is a postcard of a Fink image that Lucy loved and always kept; we are showing it alongside the original photograph. We’re proud to be working with Yolanda Cuomo on the design of the exhibition as she also worked on Powerhouse’s book. We’re also grateful to Peter Barberie, the curator of photographs at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, who has consulted with our team as we’ve developed the show.

The exhibition will include more than photographs, I understand.

RG: The images are presented in conjunction with his poetry. People think of Larry as a photographer, but besides being a poet, he was a musician, and a painter, which all contributed to his work. He explored the arts. He played piano and harmonica. In fact, he was playing the harmonica and talking throughout our first meeting. It was just fantastic to witness the kind of character he was.

He had an unusual upbringing. His parents were left-leaning, came from a Marxist background but also enjoyed a glamorous lifestyle, with big parties and beautiful cars. He often described himself as “a Marxist from Long Island”.

RG: Larry was a socialist and a rebel from the beginning, but he was not a hard-line Marxist. He was more what I would call in the world of Woody Guthrie’s type of politics. He was certainly not anti-American.

Fink took his first photographs at the age of 13. His parents would take him to jazz clubs and he photographed many of the greats, including Billie Holiday and Coleman Hawkins. When and how did photography become a career for him?

RG: Larry’s parents sent him to a college in Iowa. It didn’t last long and he dropped out after eight months. He moved to the East Village in New York where he met and photographed all the famous Beats. They had a great influence on him. His career as a professional photographer came about in a roundabout way. Larry and some friends in the East Village decided to go to Mexico to buy some dope. Off they went, and coming back to the US, they got busted. Hardly surprising, as the person who had sold them the dope had informed the police. Larry was put on parole, and when back in New York, his parole officer told him that it was time for him to straighten himself out. The probation officer realised that Larry was a talented photographer and suggested he focus on his photography. Larry followed his advice. Photography saved him.

He taught throughout most of his career. In the late 60s, one of his students at Parsons School of Design introduced him to the upper crust of New York, enabling him to photograph balls and high society parties. He wasn’t the first, nor the last, to photograph that world but he did so in his own particular way.

RG: His technique was definitely special. He held the flash away from the camera so that the light would bounce off in all kinds of strange ways and create these incredible, long shadows. The images were also kind of disorienting, in the sense that you don’t know where the light is coming in from. Larry spent a lot of time looking at art in books and museums. He had paintings all over his house. When I first met him, he told me that Caravaggio was one of his greatest influences. “When you look at my photographs, you can see the chiaroscuro effects, light and deep, long shadows, just like Caravaggio.” His highlighting of subjects allows the viewer to look at his subjects in a way so that you see them as the individuals they are.

In 1973, he and his first wife, artist Joan Snyder, moved to a farm in Martins Creek. In need of a lawnmower, he went to a local shop owned by the Sabatine family. He quickly became friends with them and he would use the same chiaroscuro technique when he photographed them.

RG: There was great fondness between Larry and the Sabatine family and they became very close. He photographed their everyday lives, marriages, birthdays, baptisms, and holidays. Some of his most important images come from that series. He was able to connect with everyone, whether they were his neighbours, farmers, or people in high society as Larry had great empathy for humanity.

His photography reached a wider audience in 1979 when MoMA presented a solo show, Social Graces, which was turned into a book in 1984. It showed two very different worlds, high society and the Sabatine family. The difference in lifestyles between those two worlds is obvious. Are there things that unite them in the way that he looked at humanity in general?

RG: I think it goes back to Larry’s own words: sensual empathy. He had an awareness of who people were, whether they were part of the high society, or working on a farm. He was able to cut through the everyday veneer and see what was going on in front of him. How people interacted, how their eyes moved. He was aware of the drama that took place in those situations. He created a stage lighting that captured people in a dramatic way so that they appeared larger than life. As a viewer, you feel like you’re watching them perform on stage. He did this all with empathy, and without deference, and that’s what separates his work from other photographers. He recorded what was going on in all parts of our society. He captured moments in time that allowed the viewer to bring their own reading of the images in front of them.

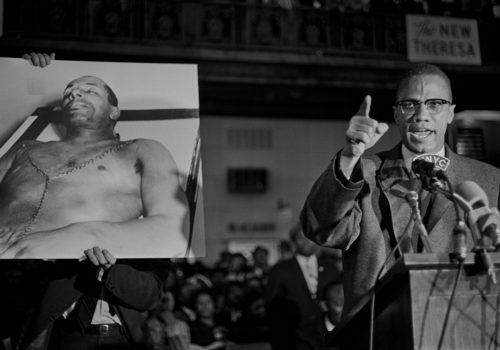

Larry Fink produced many other series, such as the boxing series and the images of the people who hung out at Andy Warhol’s Factory.

RG: The boxing series contains his seminal and very energetic work. It came about because of Larry’s love for the sport of boxing. It showed the grittiness, the difficulty, the suffering and the punishing life of boxers in a way that nobody before him had done. His Andy Warhol Factory photographs are another example showcasing Larry’s ability to access all different parts of society. It’s interesting to compare Larry’s images with Avedon’s portraits from the Factory. Larry did something different. He explored their souls as opposed to Avedon’s lining up individuals in a static formation. That was Larry! Since acquiring the estate, MUUS has had many people coming to us, wanting to share stories about how Larry did something for them, helped them, or said this or that. He was eccentric and he was very funny and he liked to perform. When you were in front of him, you were his audience. Once he found his way into what you were interested in, he got very serious and would start a discussion with you in depth.

Alongside his personal work and his commercial work, for the New York Times, Vanity Fair, and other publications, he was also an important educator. We have mentioned Parsons School of Design but he also taught at Yale University, Cooper Union, New York University and Bard College. Have you come across any of his teaching materials?

RG: We know that Larry lectured of course, and probably took copious notes, but as of right now, because of the enormity of the archive, we are still trying to find all of the pieces of this huge puzzle. The public’s knowledge of Larry is his famous images, but MUUS Collection endeavours to show the many other sides of this amazing person. Right now, we are working to put this archive in order, so that we can tell a larger story about Larry, his life, and his work.

What else do you have planned for MUUS Collection at this stage?

RG: Our main mission is to represent, preserve and showcase the estates that have been entrusted to us. At the same time, MUUS Collection is looking for more opportunities to present these archives through museums and galleries. We are also looking at acquiring more archives that speak to our wonderful stable of artists. We are constantly thinking of new and creative ways to organize these great collections. A good example of this would be our collaboration with Paulina Olowska, a Polish artist who is represented by Pace Gallery. She, like myself, is a firm believer that photography is an art form that can engage with other mediums. She credits Deborah Turbeville as her muse. When I met Paulina two years ago in Mexico City, at Kurimanzutto Gallery. She had created a series of Turbeville-inspired murals and her exhibition created a sensation in Mexico’s art world. MUUS was proud to provide some of Turbeville’s photographs and associated ephemera that were shown in conjunction with Paulina’s work. Our newest focus at MUUS Collection is creating more publications and starting a documentary programme. We are proud that a number of PhD scholars have started dissertations on our artists. Our collaboration with them has enabled them to publish their work. All of these endeavours would not have been possible without Michael Sonnenfeldt’s generosity and commitment. Michael and I share the belief that photography is a universal touchstone. We are excited at MUUS Collection to share these extraordinary collections with new audiences.

Michael Diemar

This article was first published in issue 12 of The Classic, a print and digital magazine about classic photography. You can download all the issues free here, https://theclassicphotomag.com