Zorro, or the Portrait of Another

Introduction by Marion and Philippe Jacquier, directors of the gallery La lumière des Roses

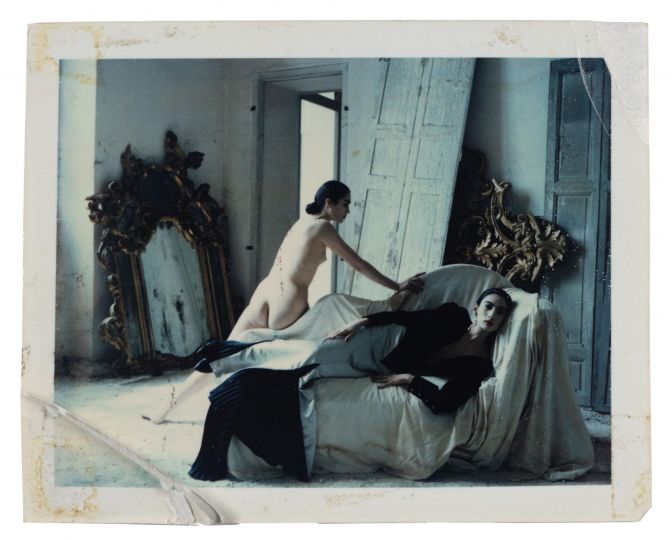

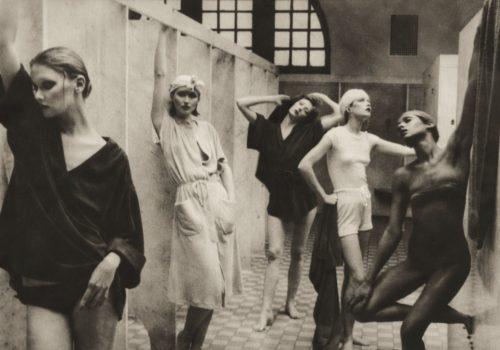

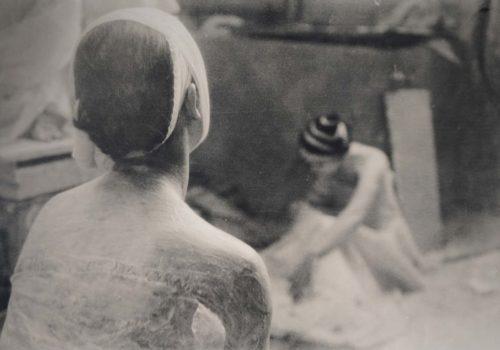

For almost thirty years a man indulges, photographically, in a double life. In the privacy of his apartment he dresses up strangely and performs for the camera in a tirelessly repeated operation. No matter that the photography system is improvised and clumsy, that nobody else will see these images. In a fusion of mise en scène and photography he gives visible shape to his fantasy, recreating himself as a hero and achieving self-induced pleasure.

Taken between 1940 and 1970, this group of some 100 photographs had remained meticulously hidden in a sealed envelope. Having no information whatever regarding their originator, we spontaneously named him Zorro, the man with the whip. And decided to let the images speak for themselves.

He is not the first obsessive practitioner of the self-portrait. From Hippolyte Bayard to Pierre Molinier, and including Claude Cahun and Cindy Sherman, photographers have often turned their cameras on themselves, bringing brio and sometimes humour to their illustrations of Rimbaud’s celebrated “I is someone else”. For Zorro the self-portrait was a challenge rather than a game: an adventure of the imagination involving unmediated translation of the mental into the photographic; a compulsive creation unhampered by convention. There is none of the artist’s deliberation here: these are photographs of a naked obsession, and their power lies precisely in this impactful singularity.

Only chance saved these images from the fate of so many others like them, no sooner discovered than destroyed because of the breach of privacy they connote. We have spent many years scouring the vast field of anonymous photography for the occasional treasures it can yield; for us the pull of these intimate visions derives less from their private character – which we betray by publishing them – than from their mysteriousness: the unsettling oddness of photos that speak to the eye yet yield nothing of their secrets.

Text by François Cheval, Curator in Chief of the Museum Nicéphore Niépce :

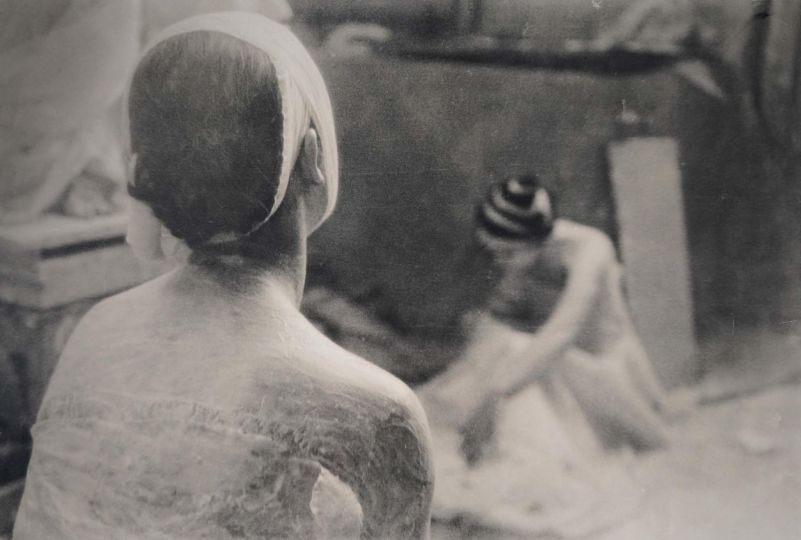

Pleasure is very often closeted. But there are solitary versions that leave us speechless. Here, in a hermetic, changeless world, an unknown – who will remain so forever – signals his presence with an outfit rivalled only by his gaucherie. We catch him facing the camera, captive of a single, insignificant gesture as he plugs a lead into a wall socket. Out of a sequence he will try to repeat some years later there slowly emerges an attempt at a manifesto, at an authentic representation of the self. A preposterous image that leaves us gaping. And once our initial stupefaction past, do these photographs deserve to be looked at again – and even more so, to be written about? This is not the first time we have been privy to the photographic spectacle of private perversity. But in this case the operation – sometimes carried out in the company of a woman we imagine to be the mother – is singular indeed. It has found its rightful place. This body, askew and perfunctorily made up, has unearthed a space to relate to. Here it structures affect, building on the interconnections between the components of the image and their reciprocal adaptation. In a corner of a room bits of furniture, a clock, a poster on the wall, form a sketchy set. For this person the decor is immaterial: the event exists only in its potential for orchestrating the dressing-up and its props. Everything is of equal value: the leather helmet, the propeller, the thigh boots, the moth-eaten shorts, the wide belt and the whip.

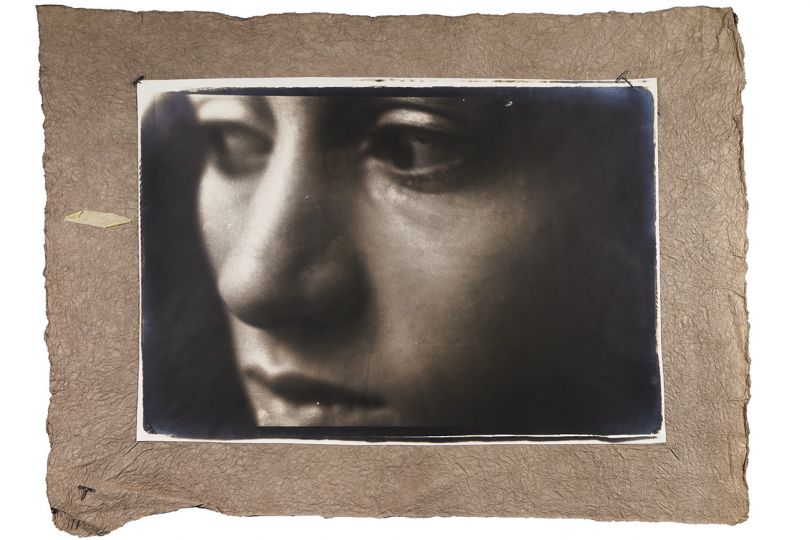

The list of equipment is too closely tied to the imagery of sadomasochism for it to be considered as simultaneously reward and punishment. The invisibility of any aftermath would seem to make it clear that excitation is being sought in the act of photography. The eccentric, unselfconscious aesthetic seems to point to the utilitarian – the facile, even – given that the fantasy itself appears uninspired. On closer inspection, the viewer’s discomfiture has to do not only with what is depicted, but also with the determination of the “hero” to control the construction of the image. The man gives no sign of any real emotion. In the concentration of the face we recognise no hint of pleasure or suffering. No contentment and even less any solace. His experiencing of emotion is disconnected from his expressions. We see no correlation between feeling and physiology. Photography, especially in this case, can tell us nothing about heart or respiratory rates, changes of temperature or other quantifiables. Assuming that our subject possesses only a reptilian brain, we must tentatively conclude that physiological observation will get us nowhere. In a situation totally at odds with erotic photography, any description of this person based on his position in the place of pleasure is necessarily chimerical. And if the pleasure is intended for later, in the contemplation of the images, the secretiveness of the experience renders any study or understanding of it difficult. We cannot evaluate what we can never get to the heart of – the happiness brought by the taking of this photo. The sole certainty one can feel about this spectacle is that some imperious urge is driving him to become someone else. Overwhelmed, he becomes one with his stratagem.

The sole situation the images make explicit is that of controlling the triggering and surveillance of this operation. Our touchingly effortful “hero” is striving ceaselessly to generate a specific sequence relating to his dressing-up ritual. The bodily restlessness we observe is in no way a consequence of any psychological restlessness. It springs from the trouble he has in plugging into a wall socket! And for what, we might well ask. But this, in fact, is the “truth” behind this inept series. Each episode is only a source of worry for him. We are witnessing a repeatedly renewed attempt at a snapshot resulting from a coordinated act. Clearly, the underlying point eludes us. This man is fighting like a demon to set up a photographic situation, a rendering of a complex to which he alone has the key. The triggering of the emotional situation is directly connected to the act of plugging in: he repeats the operation often enough for us to be sure of that. The photographic event is something decisive for him. He has great hopes for it.

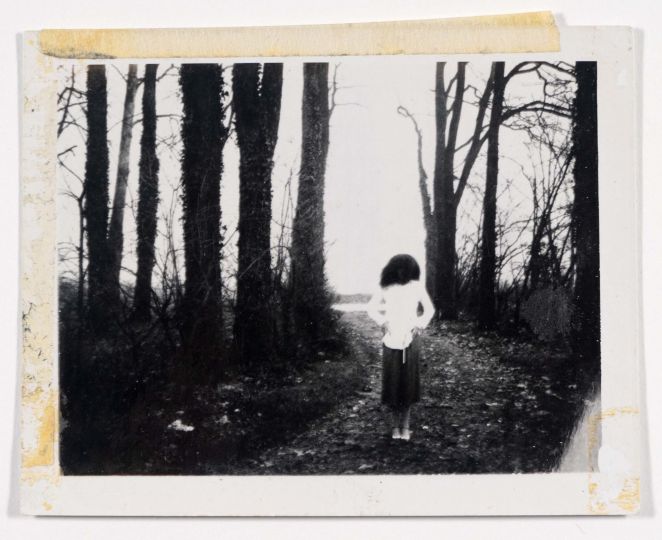

He is convinced that by plugging into the socket he is going to unleash a force transcending representation and the situation as such. The stimulation associated with the triggering of the emotions to come is the actual trigger. The programme – because this is what it is – presupposes a mise en scène focused on the socket: let there be light. We see him possessed, sometimes grimacingly disfigured. The obsession with that liberating gesture eclipses everything else. He overdoes things in his devising of a pointlessly complex system. Poise and counterpoise intermingle. The dressing-up routine is only relevant and meaningful in the context of this photographic parody. The energy given off by the acrobatically bricolaged lighting system is meant to release a potential power. Light becomes the homonym of sight. If there is to be excitation, the possible consequences of the act can spring only from the recollection of the photographic scene-setting. There is nothing immediate, then, about this experience. This is why, in his anticipation of potential pleasures, the man shows no apparent physiological reaction. Perhaps he imagines himself achieving climax at the sight of images whose interpretation hinges on the (incidentally unconscious) situation he has sparked. The actual, “original” experience has so little to offer that it exists only as potential for fantasised memories. What happens in that brief moment must be given recognition. He observes himself, presuming that he will never be seen. Being seen by another is of no importance. Likewise with conscience – Cain’s eye: since it too is invisible to the camera, he banishes it to the privacy of the photographs, along with judgement and punishment.

What happened between the two series to set him off again? Time has passed – twenty or thirty years. The female character (his mother?) has vanished, to be replaced by a kitchen stove. He marks the loss of the person who shared his secret with offerings on a little fetishist altar. A bouquet of flowers, the boots and the whip round off his grieving. The addition of the flowers aside, there are no divergences from the original experience. No variations except the appearance of colour and the disappearance of the woman. The level of affective intensity remains unascertainable. No change, then. Over a brief lapse of time the man sets out to reproduce the triggering event. We can suppose that he has gained as much pleasure in setting up this project as on the earlier occasions: let us not forget that he finds satisfaction solely in the stumbling blocks. He has not given up. He is continuing his quest for an identity through the medium of this dressed-up body. Despite advances in photography that could have spared him all sorts of difficulties, he still inflicts unlikely poses on his body. Desire is transferred to a new attribute of modernity. Buttocks resting on the domestic appliance, our man revives the magical act of photographic triggering.

Who is he trying to identify with? And what if he has simply made himself up as Zorro armed with his whip, or an aerospace hero with a propeller trophy? We shall never know. And even though this imagery exists only to be looked at, it has been created solely for him. The image, he thinks, is a merging, an effective commingling of recognition and identification. It transports reality to the outer reaches of metaphor, giving rise to a mute fiction that is destabilising because it is not intended for us. Stolen from the private sphere, the system governing this entity challenges not just our situation as voyeurs, but the very function of the photographic.

In a way we expect photography to suggest specific models of behaviour. If only we could decipher the mental state of the people we see! Maybe, by looking at these pictures, we are stating our belief in the revelatory power of the mechanical image, and its potential for clarification. The unease prompted by the sight of these images is not solely attributable to the weirdness of the situation: we find the absence of immediate meaning unbearable. Photography built its empire through the sharing of a visual culture, through a collective sense of a universal affective experience. We can all distinguish between expressions of pleasure and its opposite. We rejoice and we suffer. Yet nothing of what we know of this masquerade is relevant for its subject. Informed by our own experience, we know ourselves to be in possession of dark secrets – and yet we still have faith in the transparency of images. Photography, which aims at clarification, sides with the visible against the obscure. It aspires to demystification. But photography privacy – this is almost inevitable – is often exposed. Become the prey of collectors and museums, orphaned images are brought out of hiding and subjected to the gaze of the Other. In this new world the image that responds with an unsettling silence goes counter to “reason”.

The events we witness in photography offer an illusion of sameness. Our appraisal of them depends on an interpretation which is no more than a consequence of our experience. Innovations and modifications make no difference: they find their place in the sphere of representations only if they fit with sociocultural rules and values. Our visual roamings are systematically – and very often unconsciously – contingent on dominant social and cultural constructs. Looking at a photograph is an exploratory experience with little sense of adventure.

When we evaluate what is shown and its multiple meanings, we do it alone. Photography was invented as a way of looking things in the face. Sometimes, and this is the case here, the criteria for interaction are sundered and the habitually applicable scenarios have no point of reference. The automatic empathy of the viewer’s reactions has broken down. We will never know if, for our character, photography was a tool for keeping his life in order. It surely contributed to his survival by providing him with rapid, automated means of – of what, ultimately? We can resort to irony and poke fun at this aberrant notion of the intimate. We can feign astonishment at the endless discoveries of collections of impenetrable images combining so many contradictory objects. These images will permanently defy comprehension. But precisely because of this they will live on as enduring expressions of the photographic enigma and human vulnerability.

BOOK

Zorro

Limited edition

Introduction by François Cheval, Curator in Chief of the Museum Nicéphore Niépce

Texts in French & English

20.5 x 13 cm

EVENT

François Cheval will sign the book in Paris Photo on Thursday, November 12th at 5 pm (Stand Lumière des Roses A16)

FAIR

Paris Photo 2015

November 12-15th, 2015

Grand Palais

Avenue Winston Churchill

75008 Paris

France