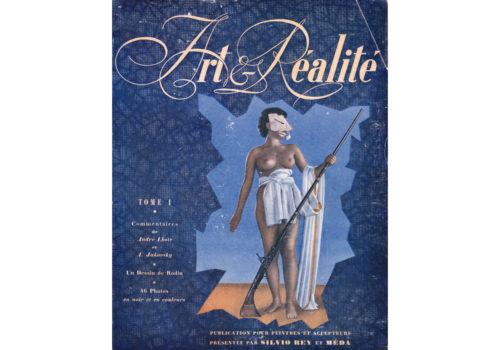

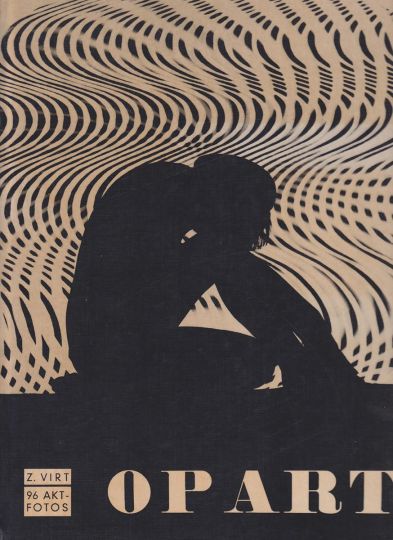

In the good thirty years which followed the experiments of André Kertèsz, we cannot consider that he set a precedent and the photographic representations of the naked body, undeniably marked by more or less surrealist inspiration, hardly invaded printed publications. To do this, we will have to wait for the anti-authoritarian upheaval of the 1970s to break the barriers of censorship relating not to the naked body but rather to the “academic” seriousness supposed to govern its representation, an unnoticed and unconscious censorship, which was no less real. This gives all the more interest and merit to those who allowed themselves early, after the war, this type of noted transgressions; I have not noted more than three incontestable examples: the first consists of a small cultural and artistic brochure of 40 pages under the title of Art & Réalité published by Silvio Rey in 1949, to which André Lhote gave a witty preface entitled Depuis quand le poil est-il indésirable? (Since when is hair unwanted?) This publication, which, in accordance with the habits of the beginning of the century, claimed to be for painters and sculptors, included almost exclusively photos of nudes, some so singular [Ill. 1-4], and unfortunately anonymous, which certain Belgian surrealists like Marcel Mariën for example, would not have disavowed; we’ll come to that later.

The second, essential, and universally known, Bill Brandt, is one of the most renowned photographers of his time, with limitless invention, inexhaustible sensitivity and very abundant printed work to show for it. stick to those of his publications which fall into the field of the nude. I will detail them in my next column.

Because there is a third photographer whom I would like to focus on as a priority today, born Zoltan Glass (not to be confused with his brother Stephen, also a photographer) in Budapest in 1903 (a year before Brandt), and therefore Hungarian like so many immigrant photographers in France (Brassaï, Kertèsz, Ergy Landau, Nora Dumas, Erwin Marton, E. Feher, F. Kollar…). Glass is almost the complete opposite of Brandt, as facetious as the latter can be concerned, worried, sometimes even tragic; The only thing they had in common was that they were both English by adoption.

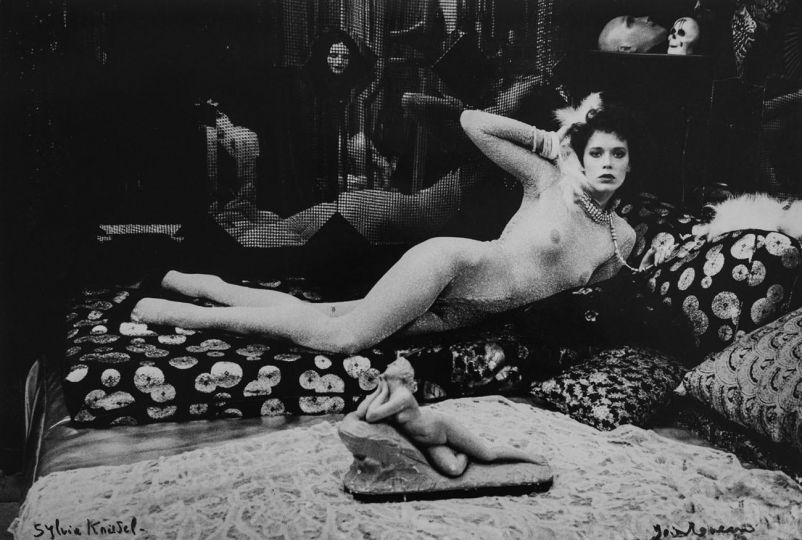

Probably oriented towards an artistic career perceptible in his various first jobs in the Berlin press, it was in London where, faced with the Nazi threat, he emigrated in 1936 that Glass’ career took shape around photography for advertising, fashion and glamour photography, whth which he asserted himself during the 1950s, with the creation of his studio-agency in Chelsea, in the beautiful districts of London. He then tended to specialize in nude photography embellished with large doses of fantasy and enhanced by demanding artistic invention, in the settings and accessories. Let us also not neglect that Zoltan selected for his shooting sessions attractive models with tantalizing anatomy appreciated by editors and readers alike. His photos were published in numerous periodicals, English (Lilliput), German (Eva and various publications from the 60s such as Akt in Lichtbild published in Munich and the anthological directory Akt 61 offered by Fravex until 1970), American (Figure photography, who with Diénès and Bunny Yeager, one of his stars in his debut, giving him two special issues, Modern Man, Art & photography, Whitestone) and French (Nus, album n°1 of the new series, SPEA , c. 1955), a time when a rather obscure German publisher, Karl Hoffman, ventured with Neue Wege der Akt Fotografie (Current paths in nude photography; Stuttgart, 1955) to bring together a selection of his creations, sole album released during his lifetime. There is a constant in all of Zoltan Glass’s creations which makes his nude photos singular, spectacular creations, challenging the viewer and establishing a bond with him. Also, his models were constantly under the visual pressure of unexpected, even incongruous, accessories – the famous props of American photography from the 60s and 70s; “The discovery and use of interesting props is a constant challenge to the photographer.” recognizes Zoltan Glass in his How to photograph beauty (Whitestone, p. 110). Among its stylistic singularities, we do not fail to notice disconcerting disproportions (the model masked by a giant king of hearts or in front of a bouquet of flowers of disproportionate size) [Ill. 6-9], destabilizing oppositions (animate/inanimate) implemented by the comparison with ancient statues or medieval armor [Ill. 10-12], the confrontation with window mannequins [Ill. 16] (gag which also tempted Helmut Newton years later for the cover of Work published by Taschen); all this perfectly explaining that Zoltan Glass’s creations easily found a place in publications aimed at an audience seeking entertainment rather than artistic accomplishment.

Browse now, ‒ better than any description, the selection in the form of a slideshow that I have prepared from the various publications of Zoltan Glass, which highlights the most significant and striking features of his style, ‒ playful and elegant. The accomplished nude photographer, very inventive and endearing, who was as comfortable outdoors as in the studio, did not know how to give up a visual gag. For the production of his images, he also readily called on his friend and accomplice, the painter James Hull, whom he asked to paint backgrounds, most often non-figurative, even cubist, some even downright architectonic [Ill. 18/20]; or he sometimes asked him to erect structures of metal tubes with him to create decorations for contemporary sculptures according to his idea [Ill. 22], most often informal; or, again, he did not hesitate to order for the adorable Pamela Green (also model of the charming photographer George Harrison Marks, whom she married), a cubist style decor [Ill. 23] or an “Egyptian” in which she appeared as the most bewitching Cleopatra.

But Glass sometimes temporarily abandoning the studio, produced his photos in the darkroom using multiple and diverse optical and chemical processes, developed over half a century; and the example of this dancer with six pairs of arms and legs [Ill. 24] is sufficiently complex to convince us that Glass was not only an inventive artist, an eye as much as an inventive decorator, but also an experienced laboratory technician .

This visual presentation of the exuberant creativity of his world has highlighted, I hope, the cheerful fantasy which commands the rich fecundity of his inexhaustible imagination. Does it not also lead us to finally deplore the oblivion into which this once incontestable famous master of the lens, whose work has been so luminous, has fallen today?

Alain-René Hardy

L’ivre de nus

[email protected]