Quite surprisingly, in these two decades when Dada and surrealism developed, these two movements showed little influence on nude photography, at least those which were selected to be printed and published in albums. Of course, Raoul Ubac and Georges Hugnet mainly, Wols, Erwin Blumenfeld and Dora Maar, shall I cite Man Ray?, produced at this time photographs that were fantastic in every way, even surreal for some (Cf. the excellent publication to the point of Christian Bouqueret, in the Photo Poche collection, n° 116, 2008), but this goes beyond the scope of our interest because none, except Jindrich Styrsky (Émilie vient à moi en rêve, Prague, 1933; not found) has was published at the time in volume.

The weight of surrealism, on the other hand, will manifest itself more massively and clearly later in publishing, as we will see in our next column. I will therefore only be able to highlight now, in this chronological section, the particular case, more or less well known, but in any case unavoidable, of the Distortions of Kertész (Paris, éd. du Chêne, 1976; introduction by H . Kramer).

At the beginning of the 1930s, the reputation of Andor Kertész, who had arrived in Paris from his native Hungary a few years earlier, was already well established: in addition to the fact that he was largely responsible for the apprenticeship of his compatriot Brassaï, then still a painter, he recently benefited from an individual exhibition in a Parisian photography gallery, and in 1932 it will be at the prestigious address of the gallery owner Julien Lévy in New York; he is praised by Florent Fels, photo columnist for L’Art Vivant, takes part in the 1st independent photography fair, represents France at Film und Foto in Stuttgart. It was then that the illustrated magazine Le sourire, a rival to Le rire created at the end of the century, and which evolved little by little from its satirical origin towards an asserted light and ribald tendency, commissioned a series of photographs from him. publish. Without any particular details. What happened then that incited him to engage with so much determination in a completely new experiment – to which his friend, the brilliant journalist Carlo Rim, had nevertheless paved the way for him in an article on Luna Park published in VU a few years earlier – an experiment which led him to direct his lens not on his naked models (which was very unusual for him), but on their image reflected in a distorting mirror (which was even less usual for him).

A mirror alternately concave and convex in its height, and even dented in its width, – as we commonly found at the time in amusement parks (I remember those at the Jardin d’acclimatation during my childhood), Luna Parks and funfairs like the Foire du Trône; extremely distorting, as for those (there were two in the beginning, as well as the models) to which Kertész resorted, monstrously distorting even. We were in 1933, when twelve “deformations” (this is the name by which they were designated for many years) were published in the early March issue of Le Sourire, under the title which certainly owed nothing to André Kertész of Fenêtre sur l’au delà. A small selection of his prints (the negatives were on glass) was exhibited in the Parisian gallery Braun, where they met with a mixed reception – from mixed enthusiasm to nauseating repulsion.

In any case the reception of these novelties, so surprising and which had enough to make the headlines, was far from being apathetic since several publications followed in the footsteps of this magazine: n° 37 of AMG (1933), with a double page with five photos, and the legendary publication Formes nues, rival of Nus by D. Masclet (1932), which in 1935 devoted two of its 96 plates, side by side with Boucher, Brassaï, Caillaud, Verneuil, to the middle of solarizations by Man Ray and Moholy-Nagy, to reproduce two of the Hungarian photographer’s “distortions”. As for the London specialist journal Photography, it dedicated a very thoughtful article to it in its June 36 issue, and although “distorted” was used several times, at no time was the word “distortion” uttered to describe the invention by Kertész.

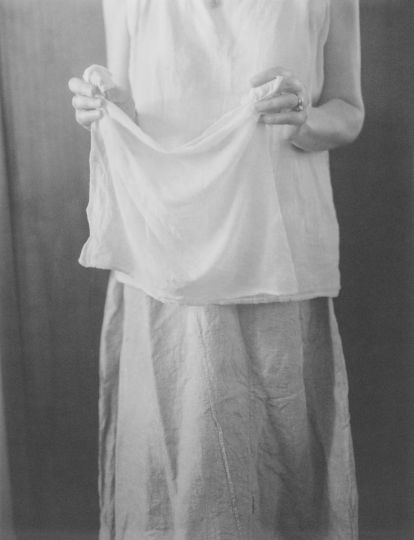

Contrary to what some might be tempted to think, it was indeed photography. There was a lens, a sensitive plate, an eye and a trigger; Above all, there was a mirror to complicate simple things and deliver a gallery of chimeras instead of an album of more or less graceful and horny nudes. This damn mirror that transforms a breast into a balloon, a pretty brunette into a Boschian demon or a super-Pinocchio. It is neither beautiful, nor touching, nor sensual; just bizarre, baroque, grotesque as the editor of Photography describes it, rather teratological than surrealist. These photos constitute an exhaustive catalog of the most distressing metamorphoses, very much in line with Kafka’s short story published a few years earlier.

In addition, here, these alterations are neither regular nor constant: the arms (or legs) look like tails, the right foot is 60 cm while the left does not exceed five. Strictly speaking, it is the making of monsters, even if sometimes a spare, recognizable organ remains, rarely. Kertész must have been taken aback when, one after the other, he viewed the photos he had taken, but he may also have been frightened by seeing these sprawling sows and walruses given birth by the unprecedented marriages of his hallucinated lens. and this bewitched mirror.

But the wheel is turning. And soon Kertész can imagine himself having a better career across the Atlantic and also wish to protect himself from the growing Nazi danger; and, called by Keystone, then subsequently recruited by Condé Nast, he will fly to New York, accompanied by his wife.

But even if this trip planned for a limited duration will last around twenty years, its sensitivity neither will his imagination succeed in really catching on with either the professionals or the American amateurs. Like a second-degree immigrant, most of his belongings (apart from his devices) remained in Paris. The deformations were left there, abandoned, forgotten… until, around thirty years later, he found them, exhumed them, had their oxidation cleaned. Let us do it justice anyway, it is thanks to the American public that they finally found their name of distortions (with a t in English) and that, forty-three years after coming out of a fairground mirror and a magical eye, the Distortions were made known to the international public thanks to the New York publisher Knopf and the Parisian Chêne, then already specialized in photography; and also thanks in large part to the photographer, now aging and hardly any more active, but undoubtedly very busy with this publication for which he had to wait so many years.

Previously, Kertész had pulled his trigger two hundred times at the Esmeralda Hotel where he worked; the plates were then numbered from #1 to #200 to give them an identity; which is why since the publication of the book, they have been designated by this issue as an irremovable title (Others are called “Impression. Soleil levant” or “La mort de Sardanapale”… It’s a matter of taste). Before the war or when he returned to France, the plates (which for the most part were to be considered as raw foundry), Kertész worked to reframe his shots himself, both to resize a large number of them and to eliminate them. slag and superfluous details). This is how three variations of the same cliché are sometimes even known.

To illustrate this unusual adventure, with accuracy and delicacy, there are two pitfalls to fear: retain only what is slightly distorted, the photos where we can still discern legs and arms, a trunk, a head or whatever. ?… and breasts too (they are women! after all). And we could almost imagine that she is pathologically obese; but an obese one all the same, not an ectoplasm (#93, 164, 157…). The second difficulty, the opposite, is to select photos representing totally deformed bodies where sometimes barely a member remains identifiable, such as for example the “seahorse” #82, 92, 117, the calf carcass #138 which will have no other consolation than having an admirable breast; or when it has become the absolute reign of the indiscernible when all that remains at the end is an ultimate uncurling to recognize (#50) or a shapeless gelatin where a few pieces of unidentified limbs float.

Alain-René Hardy

L’ivre de nus

[email protected]

PS: Since the publication of the American and French editions of Distortions / Distortions half a century ago, these photographic extravaganzas have caused a lot of saliva and ink to flow. A search for “Kertész Distortions” on Google brings back more than 40 thousand results! sometimes important analytical critical contributions.

For anyone who would like to go deeper, I recommend reading the corresponding chapter of the catalog of the Kertész exhibition at the Jeu de Paume (Sept. 2010-Jan. 2011; Hazan edr) due to Michel Frizot, to whom I owe a lot of my knowledge.

A-R. H.