“It was a lark.”

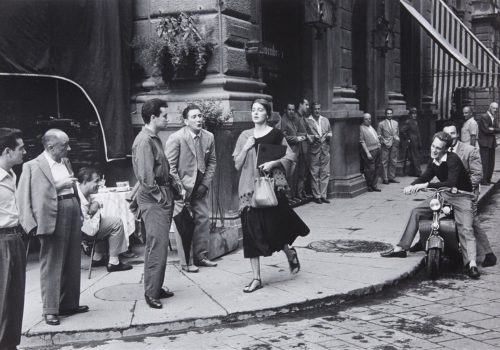

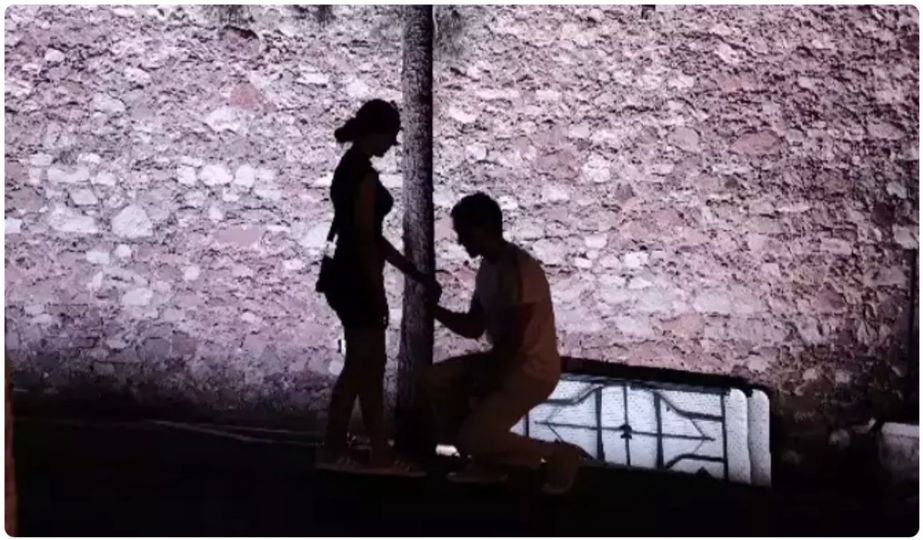

That is how Ninalee Allen Craig describes the day in 1951 when she and photographer Ruth Orkin embarked on a photographic excursion through Florence that took them from the banks of the Arno to the Piazza della Repubblica. There, Orkin shot a picture that would become an enduring emblem of post-World War II femininity—and male chauvinism.

Craig was 23 years old and, she said in an interview with me in 2011, a “rather commanding” six feet tall when she caught Orkin’s eye in a corridor of the Hotel Berchielli in Florence on August 21, 1951. A recent graduate of Sarah Lawrence College in Yonkers, New York, she was then known as Jinx (a childhood nickname) Allen.

When I spoke with her in 2011, for an article in Smithsonian magazine marking the 60th anniversary of Orkin’s famous photo, Craig said she had gone to Italy to study art and be “carefree.”

Orkin, then a successful 30-year-old freelancer, had just spent two months working in Israel for a Life magazine assignment before traveling on to Florence for a lark of her own. She was an audacious and enterprising spirit: The daughter of silent-film actress Mary Ruby and model-boat manufacturer Sam Orkin, she’d grown up in Hollywood and begun taking pictures as a girl.

At age 17 she bicycled and hitchhiked across country to see the 1939 World’s Fair in New York City. After later moving to New York she launched her career by shooting baby pictures and working as a nightclub photographer. She later married the photographer and filmmaker Morris Engel.

After meeting Jinx Allen in Florence — the photographer noted that the young woman was “luminescent and, unlike me, tall” — Orkin wrote in her diary that she “got idea for pic story. Satire on Am. girl alone in Europe.” Jinx agreed to be Orkin’s muse.

The next morning, the pair wandered from the Arno, where Orkin shot Allen sketching, to the Piazza della Repubblica. Orkin carried her Contax camera; Allen wore a long skirt—the so-called New Look introduced by Christian Dior in 1947 was in full swing—with an orange Mexican rebozo over her shoulder, and she carried a horse’s feed bag as a purse. As she walked into the piazza, the men there took notice. There was leering. One man grabbed his crotch.

When Orkin saw their reaction, she shot a picture. Then she asked her young model to retrace her steps and shot again.

The second shot from the piazza and several others were published for the first time in the September 1952 issue of Cosmopolitan magazine, as part of a story offering travel tips to young women. Although the piazza image appeared in photography anthologies over the next decade, for the most part it remained unknown.

A quarter-century after it was taken, Orkin’s image was printed as a poster and discovered by college students, who decorated countless dorm-room walls with it. The photo shot in 1951, now titled American Girl in Italy, became an overnight icon — but with a twist. The image created as an ode to fun and female adventure, I noted at Smithsonian, had been transformed by social politics into evidence of the powerlessness of women in a male-dominated world.

Ninalee Allen Craig — as she had been known since her marriage to Canadian steel executive Robert Ross Craig — died of complications of lung cancer last Tuesday in Toronto, reported The New York Times. She was 90.

To me and other interviewers in recent years, Craig insisted that the photograph from Florence had become misinterpreted. “At no time was I unhappy or harassed in Europe,” she told me in 2011. Her expression in the photo is not one of distress, she said: Rather she was imagining herself as the noble, admired Beatrice from Dante’s Divine Comedy.

“Italian men are very appreciative, and it’s nice to be appreciated,” she told The Toronto Star in 2011.

The photograph also became a focal point for decades of discussion over photography’s sometimes troubling relationship with truth. Was the event she captured real, or was it a scene staged by the photographer?

When I spoke with Craig, she was clearly delighted at her role in the making of a photographic masterpiece — and at her association with Orkin. The Times notes that she and the photographer remained friends until Orkin’s death from cancer in 1985, at age 63.

Craig encouraged young people to follow Orkin’s example, noted The Times: “‘You’ve got to be alert and quick as Ruth was,’ she was quoted as saying. “‘She had the camera in her hands night and day. She was always thinking and looking. She lived to shoot pictures.’”

David Schonauer

David Schonauer is an American editor, at Pro Photo Daily and Motion Arts Pro. He lives and works in New York, USA.

Ruth Orkin’s archive is available at: