Nicolas Boyer received a special mention of the Roger Pic Award 2020 for his series Ninety-six views without Mount Fuji, here is his text.

After more than two centuries of isolation since 1641, the first Western photographers, like Felice Beato or John Thomson, arrived in Japan at the time of the opening of the country in the turn of the 1860s, have marked from the beginning the construction of the visual & mental representation of the country. At the same time, the nascent Japonism in European artistic circles took over, in turn integrating iconic elements from the archipelago.

Many photographic studios then spread to the main cities such as Yokohama or Tokyo and various books appeared, such as “Illustrated Japan – 176 views, scenes, types, monuments & individuals” by Aimé Humbert, supposed to present a vision of Japan with an anthropological vocation but which was partial & truncated.

By highlighting certain aspects of society but also of Japanese landscapes, these photographers only took over from the Japanese authors of prints, who appeared with the modernity of Edo [the old name of Tokyo] between the 17th century and the 19th century. And those especially from the current Meisho-e or “Painting famous views” of the archipelago like Hiroshige with his series “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo”.

Over the decades, all these agglomerated features have finally shaped a collective Western unconscious made up of kimonos, yakuza, sumos and a whole series of lexical bricks participating, like a Prévert-style inventory, in the perception of this country: otaku , geisha, robots, dolls, salarymen, etc.

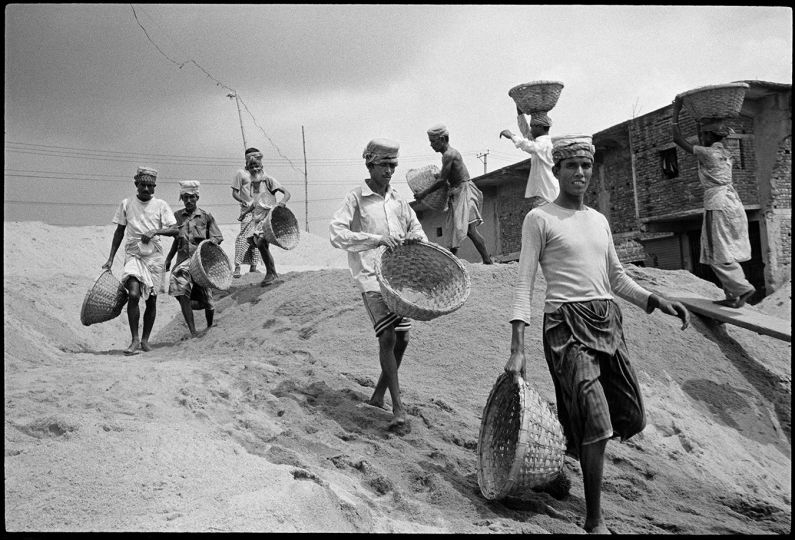

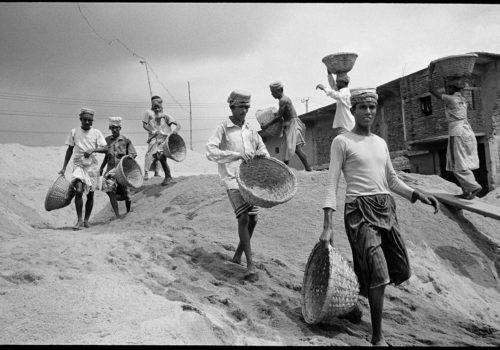

By relying on these same archetypes that make up an identity kaleidsocope, I tried to fix fleeting impressions, moments from the daily life of people caught up in their environment which is the backdrop of existences. A bit like the pictorial current of ukiyo-e [“images of the floating world”] which also valued subjects from everyday life at a time when the art of prints also allowed their “technical reproducibility” – to resume the terms of Walter Benjamin’s analysis of photography.

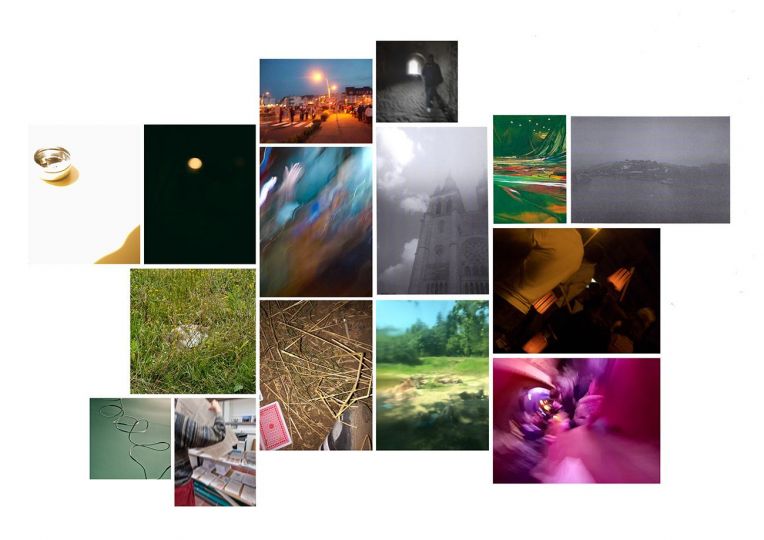

The selection of 15 images that I present is part of a larger set of about 96 “views” of Japan – without Mount Fuji as I indicate in a nod to one of Hokusai’s famous series.

We can then meet an old yakuza who repents every day by going to the local evangelical section, a player who has been uneasy in a deafening pachinko game room, the students of an upscale college in Kyoto during their kendo training. , the actors of a small neighborhood cabaret resting after their performance, salarymen who might prefer to be with their family rather than having to accompany their boss to the karaoke, a family in the traditional inn (ryokan) that they run in a small provincial town with an atmosphere close to an Ozu movie, etc.

“There are no hard distinctions between what is real and what is unreal, nor between what is true and what is false. A thing is not necessarily either true or false; it can be both true and false. “Pinter [1958 – Nobel Prize reception speech]

While working on Japan, I sought to question on a double level:

1 ° / on the one hand, the notion of national identity through the concept of common places & their potential artificiality, as I introduced them in the presentation; 2 ° / on the other hand the concept of photographic truth in the fluctuating relationship that documentary work can establish with fiction.

I have made 2 trips of about a month each over the past 2 years, traveling throughout the archipelago from the northern areas that suffered the 2011 tsunami to the south of Kyushu Island towards Nagasaki.

The French writer Michel Butor during his first stay in Japan in 1967 saw in

“This imaginary country, a magic mirror in which we make appear what we want”. For this series, I then very deliberately sought to blur the boundaries between reporting & staging, because Japan for me often seemed like a vast fiction. Starting with that of social relations where everyone seems to respect a pre-written text and where normativism forms a code that everyone must play in the name of collective harmony.

Moreover, Japan constantly oscillates between the hieraticism of the Noh theater & the excesses specific to kabuki performances. And this big gap takes place on the permanent scene that is the public space, where the divide between the day and night world is very marked. Privacy, meanwhile, is played behind the scenes and very often remains very inaccessible to everyone.

Starting from these empirical observations, I was inspired by the words of Godard who wrote that “all great fiction films tend towards documentaries, just as all great documentaries tend towards fiction. […] And whoever opts completely for one necessarily finds the other at the end of the road “. I then took the expression “making clichés” specific to photographic work in its multiple meanings in order to play on these [clichés / commonplaces] that one may have of the Other.

The few staging (15 to 20% of all 96 boards) were done systematically on site, in two minutes, trying to dialogue with the people encountered. Not speaking Japanese & the Japanese themselves having a very low level of English, I often communicated by signs or drawings to make them guess the situation I wanted to create with them. This served as a safeguard by limiting the risks of getting deeper into the artifice.

In the end, it is interesting to note that the most baroque or improbable scenes are not necessarily the least real.

Nicolas Boyer