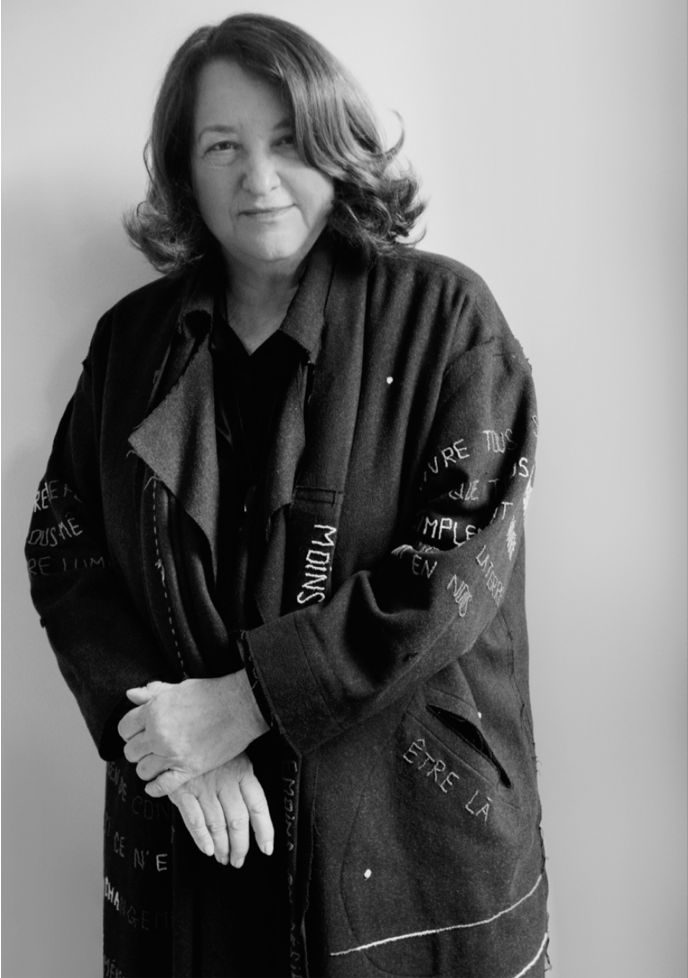

In support of Women’s History Month, The Eye of Photography proposes to rediscover this interview with American photographer LaToya Ruby Frazier, from the Women issue of the american Musée Magazine published in November 2015.

Describing a picture of yours from A Haunted Capital, you said that you watched The Cosby Show as a kid in order to escape the reality of your dismantled working-class family. When did you come to terms with the truth and what led you to embrace and document it?

LaToya Ruby Frazier: I was always aware of my plight and displacement. I am from an area known as “the bottom.” Braddock is on an incline, the further you are up the hill the higher your social and economic status. Through my Grandma Ruby’s discipline I learned that my only way up was through my education, academically and creatively. When I met my photography mentor Kathe Kowalski at Edinboro University of Pennsylvania, she encouraged me and taught me the value in making work about Braddock, my grandmother, mother and myself. All of these things led to my embracement to produce the work.

The New York Times has stated that your book, The Notion of Family, is about “the largely forgotten Rust Belt town”. How would you describe the themes and subtexts of the book?

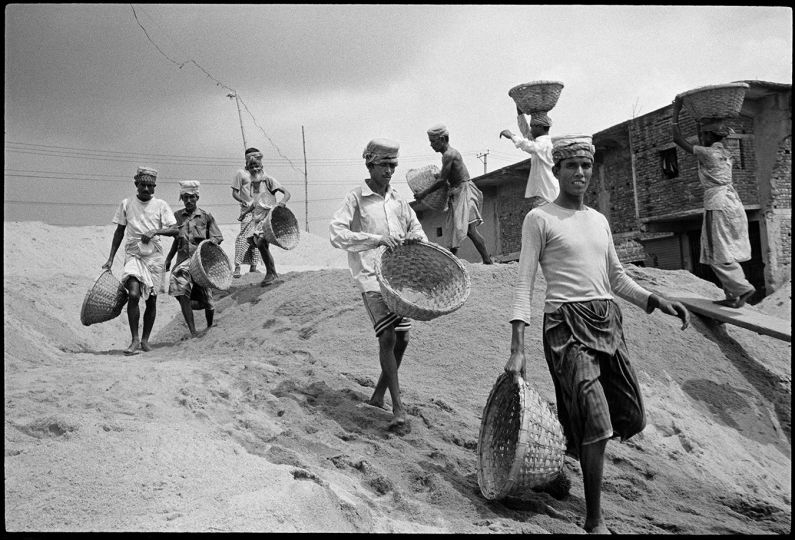

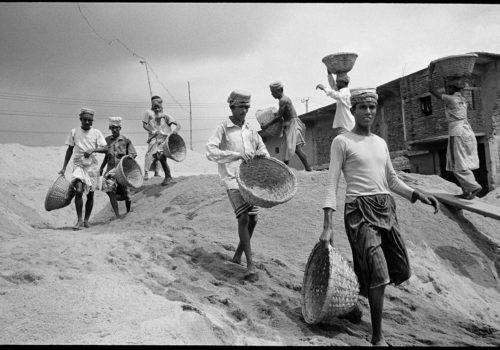

The Notion of Family is a photo-history book that tells the story of the collapse of the steel industry and global economy through the bodies of three generations of African American women (my grandmother, mother and myself). Aspects and intersections of the book are the steel industry, environmental pollution, and healthcare inequity.

You began toying with the camera lens at the peak of your adolescence. Which one of your photographs, from that period, means most to you even today and why?

In my intro to photo class I was given a dead-pan portrait assignment where I chose to make a portrait of one of my younger cousins. He was standing on the side of the house in front of the tool shed holding a basketball under his arm, wearing an oversized flannel jacket and baggy jeans staring pensively into my camera lens. When I noticed how self possessed and aware he was I released the shutter. When I displayed it in class my instructor described it as an image akin to August Sander. He believed I should change my major to photography and so I did a dual concentration in photography, graphic design, and a minor in speech communications.

The image on the cover of The Notion of Family appears to be Shadow from the Momme Portrait Series. Why did you choose to use a color version of the photograph? Also, how did you decide on which photographs to feature in black and white and which to feature in color, in the book?

The concept of the cover for The Notion of Family is based on the family album; a cloth covering that suggests a history book; embossed silver foil stamping that refers to the metals like the steel industry; a reddish rustic color that refers to bloodlines and rust; the black and white image Momme Shadow, 2008, across the entire cover heightens the collaborative work between mother and daughter, the eerie shadow foreshadowing loss and the textile pattern suggesting industry.

While a lot of photographers prefer to shoot troubled societies and communities with economic disparities as mere observers, you were involved in the entire process. What was it like, emotionally, to be the photographer and an integral part of such an intense subject?

My audience has to understand that The Notion of Family is myself as a subject transitioning from a youth to an adult. I was learning so much along the way about my heritage, culture, and identity. My aspiration and hope was that I could add my grandmother, mother and gramps to the history of Braddock making sure their names and lives count. I was using my artwork as a creative solution as a means to my survival. I was trying to humanize a very difficult situation.

Your photographs are journalistic and documentary-like in nature; bold, honest and stark. Do you intend to evoke discomfort in the viewer? Also, what kind of message or impact do you hope The Notion of Family will make?

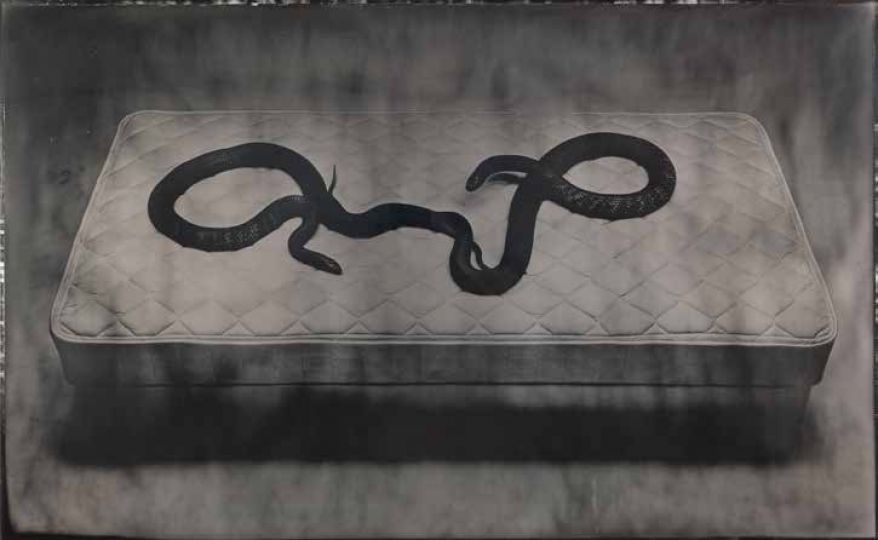

My images are informed by early twentieth century sociologist-photographers like Lewis Hine and Jacob Riis, twenty-first century documentary photographers Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, and Gordon Parks, 1970s New Topographics movement, 1980s conceptual art of The Pictures generation and Baroque period painters like Johannes Vermeer’s paintings of women. My work is not journalism at all. It is my visual expression of what it means to internalize post-industrial America. The works are akin to living tableaux; living between social realism and surrealism.

The message I am hoping to evoke for the sake of the viewer’s consciousness is when it comes to the gentrification of the Rust Belt in order to do away with racism and segregation, we have to realize that places like Braddock were never ghost towns. Families lived there for generations after the collapse of the steel mill industry without support at the local, state and federal levels deprived of basic social services and human rights. These are the people that can provide creative solutions to shape the future of the Rust Belt.

If you had to describe your dream for Braddock, what would it be?

My dream for Braddock would be a town that has equal opportunities for all residents; a place that confronts its’ history of racism and segregation in order to heal its community; a town that is all-inclusive when it comes to redevelopment and resources. A borough that respects its’ elders and posses unconditional love; a Braddock that confronts environmental pollution and toxicity for the health and welfare of it’s people.

Your grandma and mother fiercely battled cancer, your step-great-grandfather was bound to his wheelchair in the later part of his life and you have had to deal with severe lupus attacks. And despite all of this, you have achieved immensely. What has been your source of strength and motivation through troubled times?

Faith, Hope, and Love.

Most of your photographs document the challenges and achievements of the two most influential women in your life. Do you see yourself working on a larger project on women and gender-inequality?

Everyday that I am alive as a Black woman fighting for social justice, art & education, health & wellness and equal opportunity for marginalized residents facing gentrification in the Rust Belt is itself the larger project on women and gender-inequality.

How have things changed for you since the Guggenheim and TED2015 fellowships? What kind of projects do you see yourself working on next?

These fellowships have broadened my audience and have amplified the many voices within the storytelling of my artwork and I will continue producing art and advocacy works that honor and preserve residents lives.

To what degree do you work on your photographs? And in a world of phone cameras and multiple photo-editing applications and softwares, how difficult is it to stick to unedited photographs, as an artist and a teacher?

As an artist, the aesthetic must be reinforced by the concept. The Notion of Family was created based on my observation and burning question of what would Florence Owens Thompson’s portraits have looked liked if she photographed herself during The Great Depression. In order to achieve this my works had to take on the history of 1930s social documentary aesthetic in gelatin silver print format. I move freely between photography, performance and video work. I view the development of software and technologies as tools. They are tools that can be used to deconstruct and understand the society and age in which we live.

Without any formal education or training, your mother has been a stunning co-author, photographer and subject for The Notion of Family. You, on the other hand, have studied photography in detail. So, how necessary do you think it is for aspiring photographers to seek formal education?

The collaboration between my mother and I was a direct response to the elite viewpoint that only the privileged has the knowledge or knows what’s best for the disenfranchised or marginalized. Through our collaboration we demystified the idea that only outsiders can author the history and storytelling of the poor. We bridged the gap between theory and reality. This was the challenge my work had to face. Each photographer’s work depending on its subject and content will come with a set of challenges. I can’t tell photographers one specific map to take. I do believe that the lived experience is indeed a criterion for knowledge.

Interview by Andrea Blanch

Andrea Blanch is the founder and editor of Musee Magazine, a photography magazine in New York, USA.