Federico Solmi’s exhibitions, which often combine articulate installations, composed of different media such as video, drawings, mechanical sculptures and paintings, use bright colors and a satirical aesthetic to portray a dystopian vision of our present day society. Irreverent, surrealistic, and sexually explicit, the videos and the works by Federico Solmi are as he is: extravagant, rowdy and ironic. They are satires about the evilness and the vices that affect contemporary society and mankind. He uses images culled from the video game industry, pop culture, and the Internet and collages them with a historical influence to produce original artworks about the seemingly disparate subject at hand. The universe that Solmi likes to represent is the exaltation of a present that is crumbling apart. His work is a criticism of a system that approves and trusts without questioning the fragile foundation on which our culture and post-modernist society is based.

Andrea Blanch: Your work consistently criticizes the failure of modern society and the leaders who are undeservingly held up on a pedestal. Is there any aspect of government and leadership that you find to be more effective and genuine rather than dishonest and greedy?

Federico Solmi: Well, I think it’s very difficult to find authentic leadership throughout human history. The moment you want to become a political leader, you become a certain kind of person. It’s hypocritical, because power is ruthless; it’s cynical. So it’s kind of hard for me to find, even in the most utopian and idealistic leader, one that doesn’t have to deal with horrible decision-making. Because in the end, a political leader, from my understanding, is protecting the interest of just one group of people, a nation. They have to make ruthless decisions against other countries, against other interests. One of my typical examples is the figure of George Washington. Today he’s considered the greatest hero of American history. He did incredible things for American society and American people, but he did horrible things towards the Natives. He was called the “Town Destroyer” by the Lakota Native Americans. It’s shocking to see how such a celebrated hero is seen as an incredible, idealistic leader. Meanwhile, on the other side of history, he is seen as a murderer. In my Utopia, I want to see a mythical leader from 360 degrees. I want to see how it was for the American, the Native, and for others.

Are there any heroes left in the world that you can satirize?

Oh, there are plenty. I’m sure I can find a dark side in many, even the people remembered as the most incredible. I have a hard time with Abraham Lincoln, you know. I didn’t want to put him into the mix, because I genuinely like his history, but I know he had some dark sides, too.

One of the reasons why I think your art is so successful is because you use satire—and use it well. What brought you to this device?

I was always interested in being an artist, but I didn’t want to just be an artist who creates patterns, or makes objects to feed the aristocracy or a self-referential art world that doesn’t look at what’s happening in society. I became a writer simply because I want to speak about society. I found myself getting very into making drawings and paintings, after that I understood that I want to tell a story. I wanted to create a narrative work, and I thought that the best way to make an impact on the viewer would be to use my drawings and paintings in combination with moving image, with video. I want to speak about why we are here, what’s going on in society, what’s going to happen in the next fifty years if we keep on this course. I’m interested in finance, I’m interested in politics, I’m interested in art, of course; all of these mixtures that I expose myself to helps me to create my vision.

So how does the structure of satirical critique compare to a more conventional commentary?

Oh, I don’t think satirical critique was ever really embraced by the art establishment. Artists like Goya and Daumier were challenged. Especially Goya, his later work was never exhibited. I think when you do satirical work, you’re criticizing the leading hierarchy of art, politics, business—any power structures in society. Those people in power don’t like to be criticized, but to me, the artist has always been interested. They were the ones that were saying, “Listen, all of these fake castles that you build—that you celebrate in business, in literature, in politics—a lot of times it’s a bunch of lies.” Goya’s most celebrated period was not the one where he was making the portrait of the king, but the dark period. People don’t want to see their weakness mirrored in a painting. They like to be disconnected from the problems of society. So in my work, I put what I think about society in their face, and I don’t see any other way for me.

You are putting it in their face, but it has a humor to it, even though it’s very serious. You say people don’t want to connect with that, generally. Why do you think people have connected to your work?

I think they don’t want to connect because usually satire is not very elegant or polite. It’s always brutal, direct, grotesque, and aggressive. I think my work is connecting better now because I am astute with experience, and of course I’m becoming an older and more mature artist. In the past, it used to be very aggressive, bloody, and stereotypical, because that was my way of doing things when I was younger. Now I think the satire and all of the critique is more polite—but also more efficient, because I understand now that you can be very efficient without being outrageous and obnoxious. You can direct your point without being cut out of events.

But speaking as your audience, there is—well, you know, I think your work is genius—but there is a grotesque aspect to it. The characters look grotesque, but it is so funny. And I think the colorful aspect combined with the animation come together so you don’t focus on one thing. It’s a whole. I was mesmerized by all your detail in the work itself and how much effort must have gone into creating it. So, all the things you’re describing about satire that don’t work, you do have in your work, and it does works.

No, but what I’m trying to say is that now I am able to basically have much better, and less obnoxious artwork. I used to do that purposely—that was me. I’m very happy that I did it, that I have criticized and been visually overwhelming, obnoxious, violent, and sexy. But if I wasn’t able to reach this politeness, I would simply be cut out of many of the events that I’m invited to today. Many times in the past, I was simply crossed out from museum shows, because I was considered, as an artist, ‘too much.’ And I didn’t change because I felt I had to change; I changed because of something connected to my maturity, and I feel so much better that now I can be aggressive, grotesque, satirical, but in a smoother way. I think that is the key of this body of work.

What kind of impact do you feel it has on your audience, and what kind of reaction or response would you like your audience to walk away with after they see your work?

I think if I go back to the beginning of my career, the idea and the goal in making art was to make the audience reflect on the subject that I was choosing. Basically, no matter what theme I choose to investigate, I want the audience to not trust what is put in their face. Just try to dig and have a deeper approach to everyday life. Nobody questions the nature of politics and the society in which we live. Sometimes my wife says, “Federico, you should settle down and try to see the world as less malicious.” But at the same time, I feel like that’s my call. I’m here. I’m on a mission. I was on a mission when nobody gave a shit about what I was making, and I think that’s what I wanted to do: to destroy myth. To destroy what people believe and take for granted.

Do you tailor your work to any specific audience?

I think my work speaks amazingly to younger audiences because I use a lot of technology. I think today, the older audience has a hard time connecting to my work. I’m using tools that ten-year-olds are familiar with. I’m talking about video game technology and all of these interactive elements in my work that children are growing up with now. At the same time, I wanted to combine traditional media like drawing and painting with technology to make something relevant and lasting. I remember in 2002/2003, when I did the first one-minute narrative video combining game technology and paintings and drawings, I said, “Wow, I just need five of these videos to convince people.” It took five years. Each three-minute video was a year of work. Then things started to happen.

How did you begin producing art? Do you have a specific background or upbringing that contributed to these political and cultural pieces?

No, my family were incredibly nice people, but they were completely uneducated. My mother went to elementary school, but nothing beyond that. My father was a butcher, so I grew up in an environment where education and culture was kind of like a crime, like a waste of time. But in Bologna, where I grew up, art and culture were in every church, in every street corner . It started to become relevant for me, and I felt like I was living a life that didn’t belong to me. When you feel completely cut out from education, you develop this tremendous, unbeatable desire. So I started to study and research with such energy and devotion that it was like I had found God. I pushed this escape from the life I was living with so much intensity that it was so obvious that I had to become an artist. It was like inventing a life.

So how did you start producing?

I think the first three or four years after I came to New York, it was just about observing. The big turning point for me was moving to Dumbo, in Brooklyn. I was able to rent a studio in 2002 on Jay St. I started to develop my drawings; I started to do open studio, and all these other things, and I started to look at other artists. It took a while to develop a body of work. I was ready to show work when I was 30.

Were these drawings and paintings?

They were mainly drawings. Very neurotic, very busy. It had a very positive effect on me to be in Brooklyn and to be exposed to this first wave of Williamsburg and Dumbo and all of these underground environments. My first show was in a Brooklyn gallery back in 2005. I knew that all of these galleries were doing okay and that they were going to move to Manhattan. So before long my work was in Chelsea. I ended up in the Art Fair, and that was the first week or so that I had visibility. And around the same time, I started exhibiting in Europe, so things started to happen.

And still not the kind of work you’re doing now?

The kind of work I’m doing now I started in 2003/2004 when I did my first video animation. The first animation was integrated in a large drawing installation. I placed a monitor inside a sculpture, it was very rudimental. I remember when I did my first animation, using Grand Theft Auto, it was life changing for me. I still wasn’t selling anything, and nobody wanted to show my work, but I knew there was a big change. I said, “I need five years. I need five videos.” And I started to put together some really cool early work, which I still exhibit today.

So, tell me a little bit about your process.

The things that I struggle with the most are not the things that people see. The hardest part is putting together a narrative for a series. I struggled a lot putting this Brotherhood series together, and amazingly, suddenly everything started to come together. Once I have a narrative, I start to sketch the characters by hand, doing drawings. Then, I hire a 3D modeler to create 3D models of each character and we replace the digital texture of each character with hand painted textures. You end up with a 3D character that is dressed with painted textures. After, I create environments that I make in the video game engine that we shape and create at the studio by modeling with all this software. Then everything is texture mapped with hand-painted drawings. Once we have the environment and the character—which in this case took six months and ten people working—I started to develop individual storyboards for each video-game painting that we created.

You had told me that you teach at Yale, but you don’t have any kind of traditional credentials to teach there. I’d like to know how that happened and what you teach.

I was invited at Yale to do a series of lectures, so that was the turning point. I was part of this fantastic exhibition that happened in Site Sante Fe Biennale. It was a show with twenty artists, all of the best video artists you can think of today, and a professor at Yale, a young guy named Johannes Deyoung. He got in touch with me, saying, “I put your video in the graduate program at Yale. Would you like to come do a lecture?” And I agreed. I started corresponding with Johannes, and they invited me several times. The last time, they said, “Federico, what do you think about teaching a class?” I’m teaching an interdisciplinary video class; we are basically doing what I do in the studio, using game engines to create narrative and interactive video work. I have to say, America, which I often criticize in my satirical work, is incredibly receptive. When I was 35 years old, I got a Guggenheim Fellowship, which is one of the best academic recommendations you can have in the United States, and I didn’t go to college! I didn’t have anything! Which means that, despite all of the problems and the crises and violence or whatever, it’s still an incredible country, because it allows people to come here with nothing to show except hard work—and they’re receptive.

You’ve produced an impressive amount of work. What pushes you to work with such vigor and frequency?

A true artist, in an older sense of the word, is someone that is always constantly trying to master his ability and never sees a perfect work. He’s always looking unconsciously to improve himself, to go deeper, and to use every minute of this life to shape his idea. I always tell my wife, “Listen, I would never retire.” She says, “What if we won the lottery?” I say, “I will be old with you, but I want to keep working.” To keep sane, you know?

Your work has evolved dramatically since your ironic Safe Journey in 2003. Why did you introduce color?

The big turning point was the video called The Evil Empire, which was a really explicit work about the abuse of the Catholic Church. In order to portray this awful fictional pope, all the environments in which this character lived were like gold frescoes, and color came with that. So, going back to what we said before, what is grotesque, what is caricature, is when you take an element of a pictorial project and you exaggerate it in an obnoxious and nonrealistic proportion. So this overwhelming color that you see in my work acts like a bombardment to the viewer. Going back to the issue of chaos, it’s sort of transmitting the sense of anxiety—an overwhelming chaos—that represents the big metropolis in the 21st century. I like to overwhelm the viewers, to bombard them sometimes.

So tell me, what ambitious project are you working on now?

Right now I’m working on an exhibition that is opening in August in Venezuela in three locations. It’s an unusual event. It’s a big museum solo show in a nation where politics have taken everything away from their people. Of course, it’s a show that won’t generate a single dollar, but I’m excited about the challenge. Also, instead of making a catalog, we are making a coloring book based on my drawings. The title for the show is “Counterfeit Heroes,” and basically we’re going to distribute, free-of-charge, all of these coloring books with each of the characters, like George Washington and Mussolini, so that people can take home a coloring book that shows these mythical political leaders alongside the reality of their politics. Of course there’s a problem with censorship that we’re trying to figure out, also the event is sponsored by the American Embassy and the Italian Embassy, so I have to be careful about what leaders I pick to feature. I’m also going over some thoughts I have about the next series with my assistant, who’s basically my shrink right now. At the moment, I’m very focused on American history, American society and American historical context. We’re about to have the election in 2016.

Do you have anything on Donald Trump?

Absolutely. I’m interested in Melania Trump, too. That couple is like a caricature. It’s going to be very difficult for me to do a satire on a satirical character. But I’ve studied American history quite a bit, trying to be informed before making work about it, and I think that the history of this country has always been problematic. Politics has always been the game of the super powerful. Maybe it was an exception with Obama, but he was still a Harvard-educated man. He’s one of the few that I really admire, but there is a system that makes it impossible to create your dream and your utopia. I think Obama is a very good example to show that the system is so corrupted that the most idealistic person is completely paralyzed.

With your lack of formal education, how important do you think art school is for children now?

Honestly, I think that the school system in the United States is very perverted, particularly the art education. I think all of the weakness you see in the art comes from art education. To be more specific, most of the students go to grad school for networking. Not even to study, just to build a network. It’s depressing that people are willing to pay $150,000 for networking. Who has $150,000 to go do an MFA? Our profession is becoming a profession for the elite. Our education is becoming very mild. Everyone is so polite, they’re so afraid to speak out. There is no animated conversation about art. It makes me believe that whoever is considered very important today from this bureaucratic structure will be nothing in fifty years. The art world is ruled by art consultants, Wall Street tycoons, and a few galleries. So I feel like we live in a very perverted environment. I don’t want to be corrupted by all of that. I never give a damn about what is hip or what is trending. It’s not that I don’t care, it’s that I don’t trust them.

When you came here with nothing, what did you live on? Did you have a second job?

Absolutely. I’ve always been very hardworking. When I first came to New York, I had saved some money in Italy, so for the first two years I had enough money to just observe. Then, I had to do any kind of job. I did everything from modeling to plastering walls. I think it’s important to be exposed to the most corrupt of society while in the craziest, most innovative environment. An artist is someone that is able to digest and understand the course of society before many average people are able to. There’s got to be some magic about the artist, they cannot just be crazy. I have to think that what pushes me to do all of this is beyond just being crazy, it is like an extreme desire for clarity. I think from an outside point of view, it looks like madness, because there’s not much money involved. If you’re lucky you can pay expenses. There’s this perception that with success, money will follow, but the reality is you barely have the money to do the next series. And things probably are not going to change.

So what do you do, get funding from people or…no?

No, not really. Basically, whatever I sell goes into the next project. We’re not talking about making serious money here. It’s a labor of love. The big money at the moment is in the most predictable art. That’s obvious. If you’re not predictable, you just get kicked in the ass. And it’s always been like this. You do predictable, luxurious, and well-packaged art, and you get ahead. But I have zero interest in that.

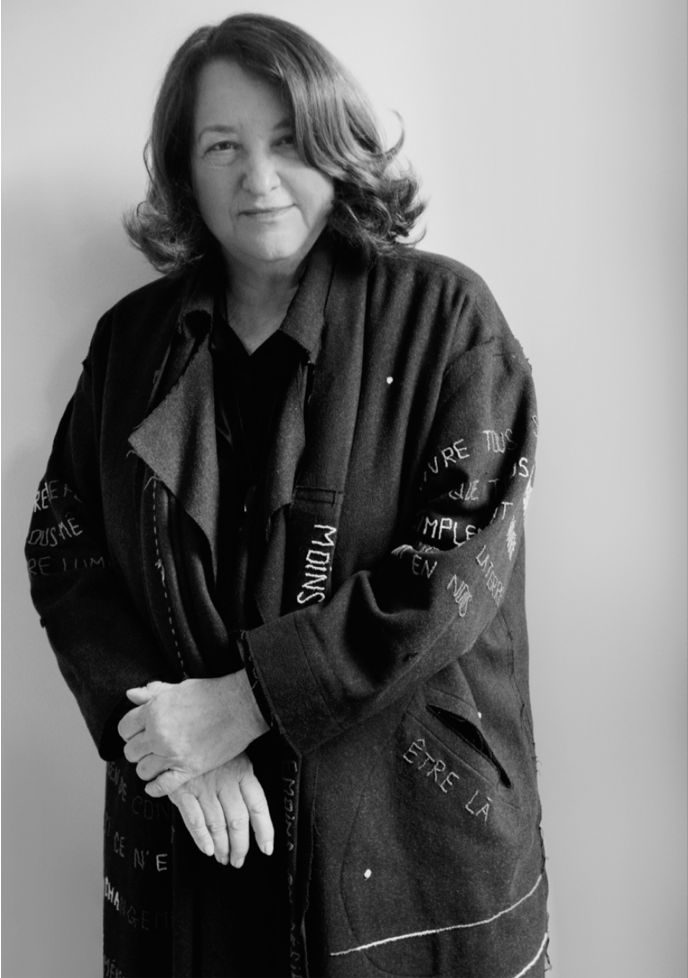

Interview by Andrea Blanch

This interview was published in the issue 16 of Musée Magazine that came out in October 2016 and is available for $65.