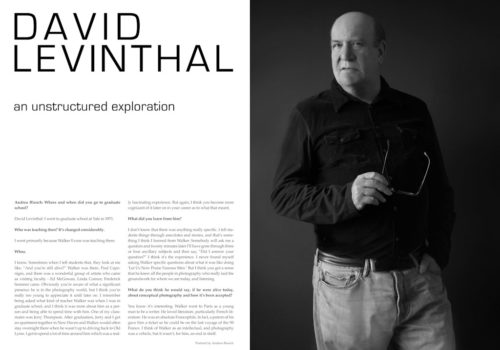

Musée Magazine’s Fantasy issue is online now. Fantasy, Vol. 1 features a selection of art work and exclusive interviews with: Didier Massard, Laurent Chéhère, Slater Bradley, Thomas Wrede, Zoe Crosher, Rona Yefman, Thomas Struth, Chris Boot and Julien Frydman. We really enjoyed the interviews of Sondra Gilman and David Levinthal, by Andrea Blanch.

David Levinthal interview :

Andrea Blanch: Where and when did you go to graduate school?

David Levinthal: I went to graduate school at Yale in 1971.

A.B: Who was teaching then? It’s changed considerably.

D.L: I went primarily because Walker Evans was teaching there.

A.B: Whoa.

D.L: I know. Sometimes when I tell students that, they look at me like, “And you’re still alive?” Walker was there, Paul Caponigro, and there was a wonderful group of artists who came as visiting faculty – Ed McGowan, Linda Connor, Frederick Sommer. Obviously you’re aware of what a significant presence he is in the photography world, but I think you’re really too young to appreciate it until later on. I remember being asked what kind of teacher Walker was when I was in graduate school, and I think it was more about him as a person and being able to spend time with him. One of my classmates was Jerry Thompson. After graduation, Jerry and I got an apartment together in New Haven and Walker would often stay overnight there when he wasn’t up to driving back to Old Lyme. I got to spend a lot of time around him which was a really fascinating experience. But again, I think you become more cognizant of it later on in your career as to what that meant.

A.B: What did you learn from him?

D.L: I don’t know that there was anything really specific. I tell students things through anecdotes and stories, and that’s something I think I learned from Walker. Somebody will ask me a question and twenty minutes later I’ll have gone through three or four ancillary subjects and then say, “Did I answer your question?” I think it’s the experience. I never found myself asking Walker specific questions about what it was like doing ‘Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.’ But I think you got a sense that he knew all the people in photography who really laid the groundwork for where we are today, and listening.

A.B: What do you think he would say, if he were alive today, about conceptual photography and how it’s been accepted?

D.L: You know it’s interesting. Walker went to Paris as a young man to be a writer. He loved literature, particularly French literature. He was an absolute Francophile. In fact, a patron of his gave him a ticket so he could be on the last voyage of the SS France. I think of Walker as an intellectual, and photography was a vehicle, but it wasn’t, for him, an end in itself. I remember back in those days when I was applying for teaching jobs, letters of recommendation were still confidential. This one university that I had applied for a job I didn’t get, sent me back my portfolio and inside the portfolio somebody had inadvertently stuck the four letters of recommendation, including Walker’s letter. Walker’s letter was short but it was so touching to me because what he said was that he felt I was a very unusual and special talent and that I would be a great asset to any photography program. He never said that to me personally but I was very touched that even though I was off doing this crazy wacky thing, he saw something in me and could project forward that it would be something of interest and significance.

A.B: It seems that you have an awareness of political and social issues. Where does that stem from? How does that tie in to your work?

D.L: Yes. I went to college in 1966 at Stanford with the intention of becoming a constitutional lawyer. It was the 60s and I came from a liberal household. The 60s were very a transformative time. Law seemed a way to pursue social justice and changes. I was going to be a poli-sci major and go off to law school and obviously, things changed. It was also the Bay Area in the ’60s. The Free University which was essentially non-credit classes, total- ly unstructured. Anyone could teach a class on anything. One of the classes, and I tell students this story, was a class called LSD and Tantric Yoga.

A.B: I knew I went to the wrong school.

D.L: I took this photo class because it was taught by someone who was the sort of essence of coolness and I thought, “Well, Dwight’s cool. I want to be cool through all this, and all the beautiful women around him. This sounds like a good idea.” And so I signed up.

A.B: Are you shy?

D.L: Yeah, which is funny because when I came to New York in 83, I forced myself to be social. You’re always told to go to openings, meet people, which is not easy, but I looked at it as a job. I needed to do these things.

A.B: Where are you with your work now? Are you still doing social landscapes or the toys?

D.L: No. Once I started working on the toys in graduate school, I continued. Actually, after Garry Trudeau and I graduated in the summer of ’73, his publisher suggested that he and I do a book together. He had created a biography of a faux German Luftwaffe (the pilot), and did it all with graphic symbols. His publisher saw Garry’s work, and my work at that time was very simple. I had been photographing on the floor with minimal backgrounds. They said, “Well, you know, you two guys should do a book together.” We looked at each other and thought, “Well, that sounds like fun.” We got an advance of $1,500. I remember when Garry gave me my check for $750. He looked at me and said, “Now, just remember if you cash this check, we actually have to produce this book.” Now, our contract said we had a year to do it. It took us three and a half years, for lots of reasons. One, Doonesbury was becoming such a significant force in the social and political landscape. I think Garry was the first cartoonist to get a Pulitzer.

I was taking pictures with unpainted tiny little figures to the point where the images in the book were all of these larger models that I had made and painted, much more articulated. I remember Garry’s explanation to Jim Andrews and John McMeel, he said, “Well, the reason it took us longer to do the book than it actually took to fight the war was that we have to clean up afterwards.” But my work evolved tremendously and spending that amount of time focused on it really brought me to the point where working with dioramas and toys became what I wanted to do. When the book came out in ’77, I remember going to B. Dalton’s Bookstore because I wanted to get a copy for my parents that was wrapped up in their paper. They had it in the history section because there was no photography genre that it really fit into. I find it so interesting that Garry and I just did a reissue of the book, a 35th anniversary edition. Garry’s suggestion was that we do it larger, a bigger book and I said, “Is that because we’re both over sixty and this is the big print edition?” His feeling was, and he was absolutely right, was that it gave a great presence to the photographs. At that scale, they seemed even more powerful.

A.B: They are.

D.L: It’s very gratifying to see work that you’ve done become even more relevant and more significant. I remember years ago, Elizabeth Sussman at the Whitney took Garry and I to lunch and there were some Hitler Moves East photographs and a couple of his layouts from the book. As we’re walking through the Whitney, Garry looks at me and he says, “Did you ever think when we were sitting in New Haven, eating hostess cupcakes and drinking Coke that this work was go- ing to end up in a museum in New York City?” I think part of the reason that Hitler Moves East is the way it is, is that we were so oblivious to any boundaries or constraints. Looking back on it, we were breaking all kinds of rules and things but that’s not what our thought process was. I would think, “Well, how can I make a wheat field? How can I make snow?” It turned out the wheat field was grass seed and the snow was Gold Medal flour which I continuously recommend to students who want to create snow. It’s one of my favorite photographs. One of the signature pieces, the explosion where there are soldiers flying to the mid-air, Garry stuck a pin in one of the soldiers and so he propped him into my little mound of grass which he used to refer to as my miniature golf course. It was about three by three feet on this big table I had. I had sprinkled a little explosion powder and Garry lit it with a cotton ball and it kind of went poof. He said, “Here, give me this.” And he starts shaking it like an eight-year-old putting salt on French fries. He lights it. There’s this sound like a shotgun going off. The cotton ball flies across the room hits the window and bounces back. The negative is almost opaque but it was this great photograph that literally looks like the soldiers flying to the air. Garry said, “You know if I knew you were having so much fun doing this, I would come over more.” There was an unstructured exploration of how do we do this and without any regard to what would be con- sidered traditional photographic work.

A.B: Is your lighting setup complicated?

D.L: No. Most of the time it’s embarrassingly simple. ‘Hitler Moves East’ was done in my apartment in New Haven using one of those old-fashioned, big metal reflectors that you put the light in. It was a metal dish and I bounced the light off the ceiling. That was it except for the light that came from when I would light a building on fire. That was additional lighting. I would say now it’s probably more sophisticated because they make lighting specific for tabletop work.

A.B: Were the Wild West and Desire series commercially successful at first?

D.L: I’m glad my wife isn’t here… I had an old girlfriend who was a curator and she said, “Your work is always going to be discovered five or six years after you do it,” like the American Beauties which are now pretty much all gone. So, they weren’t too commercially successful at that time. They sold a little bit. I would say with the exception of the cowboys and Barbie, there’s always been this sort of lag between when the work is done and when it starts to sell, which is hard at that time. But in retrospect, it’s kind of great because I still have the work, and the prices have gone up considerably, and essentially all the 20x24s are vintage prints. I mean people are still doing some 20×24 work, but it’s not really the same.

A.B: Have any fashion people ever approached you to do something for them?

D.L: I think the closest I came was the Barbie project. I was asked by a publisher to do this book for Barbie’s 40th birthday, which was 1999, and I initially said no because I had photographed a Barbie doll in grad school with a G.I. Joe and later I showed the work, I guess maybe four or five years ago, with John McWhinnie. We called it Bad Barbie.

Years later, it’s now high art and very expensive. But the Barbie book, they asked me again and I think had seen Funny Face on AMC and I thought to myself, “Well, if I approach this like I am a fashion photographer, this is going to be the only oppor- tunity I ever have to be a fashion photographer.”

I took a late 50s, early 60s approach to it that you saw in the movies of those days, like what Audrey Hepburn or Doris Day were. I picked colors with that time period in mind, a bright pastel type color. It was a fun project and I think that’s one of the reasons why we ended up focusing so much on the earlier Barbies that really had a fashion sensibility about them.

But no, I’ve never been asked to do fashion work, although I’ve always felt that there’s a great deal of similarity. I said that when I was doing the Triple X work that it was like I was photographing Playboy bunnies. They had equal amounts of artificiality in them. Mine had the advantages of not going out at 3:00 in the morning and doing drugs, and they were all set to go at 10:00 in the morning.

A.B: What is something you’d like to talk about and that you’ve never been asked?

D.L: I remember when I was in graduate school I was sharing a house with two third year law students and I remember one of them asked me, “What happens if you run out of ideas?” And I remember saying, “Well, it never even crossed my mind.” I feel in some ways I’m more concerned about staying around long enough to work through the ideas I already have because there’s just so much. One of the things that I find really interesting and kind of liberating about doing these historical iconic images is in the past I might do an entire series say of the Civil War. Now, I can pick moments like Lee’s Surrender or a charge of Gettysburg and so it’s very, very liberating, and it allows me to sort of delve into something without feeling that I have to complete it.

A.B: When you create your work, do you think about the person who’s going to be looking at it and what kind of response it’s going to evoke or provoke in them?

D.L: I think at this point it doesn’t cross my mind. When I was younger I would from time to time think about it, but I’ve always looked at my work as problem solving. I have an idea of what I want. I may end up with something completely different, but I’ll really focus on that as a starting point and then I let the work take its own direction. I always tell students, “You start out with an idea and you may end up some place completely different, and allow yourselves to do that.”

A.B: In your own words, how would you describe yourself?

D.L: Introspective, lost in my own world…

A.B: When did you start thinking of yourself as an artist?

D.L: Probably when I went to graduate school. I would guess because as an undergraduate I was a film major briefly, a classics major, I took a nuclear physics class and my father was a physicist. He told me, “You don’t have to be a physicist because I’m a physicist.” He talked to a couple of his friends in the art department including Professor Conn and Matt said to him, “Yeah, you know David really has talent,” which was very nice to hear. But my father said something else. I remember we were sitting in the car in the car port, he said, “Talent is necessary but not sufficient criteria for success.” I found that to be so true. There are so many other factors that come into play, some of which you have no control over. I was very, very fortunate that Garry and I were offered this opportunity to do the book because having a book of your work published when you’re 28 years old is a big deal. It meant that that work was going to always be out there in some form. I’m grateful that I had those opportunities, and things have not always gone smoothly, they never do.

A.B: What’s your fantasy?

D.L: That I can live long enough to do all the work that I would like to do.

**

Sondra Gilman interview

Andrea Blanch: Photography has evolved so much in the past ten to fifteen years, taking so many different forms. How have you kept your eye evolving? You say you collect with your heart and gut, has that or your aesthetic changed?

Sondra Gilman: Very true. If you look at the things that I first collected, which were done in the early 1900’s, and then you look at what I bought yesterday, they look as if they belong on different planets. While the goal remains the same, my eye has changed. If you keep exposing the eye to everything that’s going on, then it becomes your best feature. Your eye changes, it solidifies, you suddenly realize ‘this is better than that’ and why you like something. But since I started collecting, it’s been about exposure, and I always trust my eye.

A.B: I just think it’s extraordinary that you’ve been collecting for quite a while, but somehow manage to keep up with the times. Most notably, you’ve collected for the Metropolitan Museum of Art and for the Whitney Museum. What are the differences and criteria for collecting for these collections?

S.G: Well they all have different goals. For example, The Met is much more involved in the history of photography. The MoMA really was one of the very first museums, with John Szarkowski who was an absolute rule breaker in buying and recognizing photography. The Whitney came in when I started the collection, but they had to start from the mid-70’s since a lot depends on availability. If you started early like The Met you could have a gorgeous early collection, if you started when MoMA did then you wouldn’t go back into the 19th century but the 1900’s are brilliantly represented. The Whitney came in quite late in 1990, so the availability of the earlier works were much fewer and the prices were much higher. So practicality says they have to collect from 1975 on because, one, they could find beautiful examples and, two, it was affordable.

A.B: Now with the ability to find and view art online so easily, why do people buy art anymore?

S.G: Because there is nothing like sitting down in front of a work of art and communicating with it. Nothing can replace that. The same with listening to music, it’s different playing it in your little earbuds rather than a record.

A.B: How do you think this has changed the game in your opinion?

S.G: I feel that people who want, in a way, a less ‘deep’ experience, can do that and enjoy it and get lots of pleasure from it, but you can’t replace being directly exposed to art. Nothing can substitute for the object.

A.B: Would you consider yourself a curator?

S.G: Only for my own collection, not somebody else’s. I couldn’t do it.

A.B: Why not?

S.G: I go based upon what I love and what I feel. I’ve never tried to think in somebody else’s shoes. I’ve been very lucky to do what I love to do according to my tastes, and hang things based on what I like to see together. There’s no other motivation. A museum doesn’t have that.

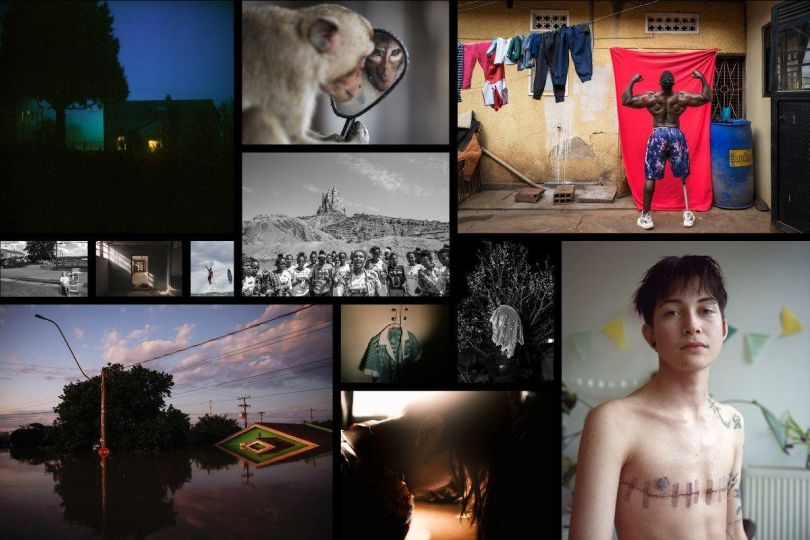

A.B: What do you think the challenges facing photography are today?

S.G: Normally you think back to years ago: you thought of your film, you thought about your paper, and you thought about a camera. That doesn’t exist anymore. We work without a camera today. People are working without negatives. People are breaking boundaries. It’s almost what happened to modern art years ago with the Modernists. All of a sudden people were thinking outside the box, breaking all the rules, doing things that were never considered before.

A.B: So there is no definition any longer?

S.G: Except somehow or other, if you use a camera or one of the other elements, you can call it “photography.”

A.B: Would you ever acquire an Instagram photo?

S.G: If I fell in love with the image, I think. If the quality of the image strikes me, but it hasn’t happened yet. Although it might.

A.B: The Instagram has become an accepted aesthetic now, and quality isn’t an issue. Is it always an issue for you?

S.G: So far it has been, but I expose myself to everything that is going on. And suddenly, as I look at it, I understand it more and will appreciate it more, and then want to buy it. I don’t have any rules. Rules are meant to be broken.

A.B: More and more New York galleries are showing work where performance art and photography are combined. As an avid supporter of theater, where do you see the intersection of performing arts and visual arts?

S.G: I think that physical performance can incorporate anything today. As I said, I think that today there are no rules; it de- pends on how good the work is, and the emotional response. I think that if anything really touches you and inspires, it works, it’s fine. You look at some of the young photographers and they’re doing installations with photographs or boxes – physical structures with photographs, combined sculptures with photography. And I think that’s wonderful! If it gives you a new experience, I’m all for it.

A.B: Would you acquire a photograph of a performance artist by someone similar to Marina Abramovic or Nick Cave?

S.G: Maybe. I have one of Isadora Duncan. And so you know, why not? If the photograph is effective, then it’s a work of art.

A.B: Are there any pieces of art or artists that have alluded you or you still want in your collection?

S.G: Now I have a problem, because I only collect vintage. And it has to be quality vintage, so it can’t have nicks or tears. So that limits what I buy. In other words, there are some images that I absolutely love, but can’t find a good quality vintage image of it. So yes, it’s really a question of finding it. And now vintage is disappearing from the market.

A.B: I’m curious, why did you decide to only collect vintage?

S.G: Because I think it’s the purest form of representing the artist as he was at the time. When he took a photograph, he decided the image. Then he knew what the paper would look like. He knew how much silver it would have in it. He was also at a certain artistic place in his life, and somebody took that first photograph or printed it within five years. It was as close to what the artist thought and felt and desired. Ten years later, the artist is in a different place, he’s a different human being. That’s not to say there isn’t value in that, but I’m a purist and I want the original.

A.B: That’s very vintage, considering the current state of photography.

S.G: Yes, it’s called making life difficult for yourself. Vintage means it was printed within five years of the negative. All contemporary photographers today are vintage, because it just means printing within five years of the negative. And that falls within my criteria.

A.B: Are there any new images that have inspired you recently?

S.G: I feel awkward saying the name of an artist, but I guess since it’s my own collection, Chris McCaw. He is a Californian artist who built his own camera, and his project begun by accident. He had the camera open one night and fell asleep, and he didn’t wake up until eleven o’clock the next day. What happened was the sun burned a hole in the paper, with the image reflected, he loved it so much that he travels all around the world and does that. So I bought that. Then there’s John Chiara who builds his own camera, it’s in a truck. He takes one image and alters it, but because of the structure, all of the colors are changed. Some of it remains the same and some of it doesn’t, and I love his work. There is Jennifer Hewitt, who is a black photographer that sort of deals with the history of her culture, and she does very physical things. I think her work is wonderful..

A.B: Is there any one photograph in your collection that has any special meaning or attachment?

S.G: The first three images I bought. They changed my life.

A.B: That was fortuitous, wasn’t it?

S.G: Well, I was a junior council at the Museum of Modern Art, and I had never seen a picture that my father or grandfather hadn’t taken. So I’m tripping around the museum and they had the Atget show, so I marched in. He was a French photographer that took unbelievable scenes of Paris, and the tragedy is that he died impoverished. Bernese Abott was a friend of his, and managed to save his attic, and arranged for the Museum of Modern Art to have all of the photographs he managed to save. He is considered one of the greatest masters of photography. This was an exhibition that I tripped into, and I had an epiphany.

The next day I went to John Szarkowski, who was the cura- tor of photography, and asked him to tell me about Atget and to tell me about photography. I spent the next three days on his office floor, and he went through every bit of photography. Then he said, “Sondra, where we have duplicate images, we’re selling them to raise money to buy additional photographs. They’re $250 each.” And I bought three, went home, and my family said, “The men in the white coats are going to come and take you to the insane asylum. $750 on three photographs!?” And I remember saying, I just bought Rembrandt’s. That absolutely started me in photography.

A.B: Do you prefer exhibitions in galleries or museums? What do you think one space has to offer that the other doesn’t?

S.G: I think museums will offer a retrospective and a relatively in depth view of a photographer. The galleries can’t afford to do that. What galleries do is show the latest work of that photographer, so you need both. You need the educational themes and you need to find out what is happening with that artist today.

A.B: What advice would you have for anyone starting to collect?

S.G: Look. Look. Look. See as much as you can, because the eye is the best asset you have. Then read, but first look, and then if you’re interested in an artist read about the artist. That won’t tell you if they’re great or not, but it will help you understand where they’re coming from.

A.B: And what about the art consultant, do you think they play a valuable role?

S.G: I do. I mean I really do. You’ve got to check their history, because you can’t have somebody who just became an art consultant last year unless they’ve got an incredible collection. But for people that don’t have the time and don’t have the inclination, what they’re buying is hopefully expertise, then that’s the next best way to go.

A.B: We hear all sorts of things about the art business. For you personally, has it changed that much? Do you like it now, or do you prefer the good old days?

S.G: Years ago it was pure, because you gained no status from your photograph, and nobody came in and gasped and said, “You paid $10 million for that photograph!” It was pure. And the people that sold it, they loved photography. Today, just like the whole art market, it’s a business. There’s hype, there’s marketing, there are all kinds of elements that didn’t exist then. Some artists are getting very high prices while others are not, and they’re not necessarily not as good. I know top artists who have not been marketed so their prices are still very low, and they’re the best artists of the century. So there’s a lot of external factors in the business now, and that’s why you’ve either got to hire somebody who is totally honest and doesn’t have any relationships with the galleries, or take the time to learn about it, to be able to judge it. Nothing gets me more upset than when I look at a work of art and the gallery owner says to me, “Oh this museum just bought it,” or, “This collector just bought it.” I don’t buy it because a museum bought it or somebody else likes it, I buy it because I think it’s wonderful.

A.B: Do you think fairs help photography or art in general? or do you think it’s taken away the preciousness?

S.G: No, not if you have a good eye. I live in the fairs. You’re exposed to much more art than you would ever be able to see. Unfortunately, to go through all of the galleries in New York would take weeks, but if you go to an art fair, you can see it all in one afternoon. And if you have judgement, you will pass by quickly those works of perhaps less quality, and you can be exposed to and maybe discover some truly magnificent pieces. I bought twelve photos at Paris Photo.

A.B: What’s your fantasy?

S.G: My fantasy is to lie down in one room and be surrounded by all my photographs.

A.B: I think you’re going to need more than one room, Sondra.

S.G: That’s why I can never achieve it.