Muriel Berthou Crestey’s book, “At the heart of photographic creation” offers a meeting with 24 of the greatest contemporary photographers.

Photographers speak. What are the regrets or surprises that punctuate a photographer’s life? What are the corresponding realization, sharing and dissemination strategies? How are the starting points, the theme, the forms, etc. ? What are the moods of photographers? How have new technologies changed their practices? To answer these questions and many others, Muriel Berthou Crestey met photographers representative of various movements of the contemporary era.

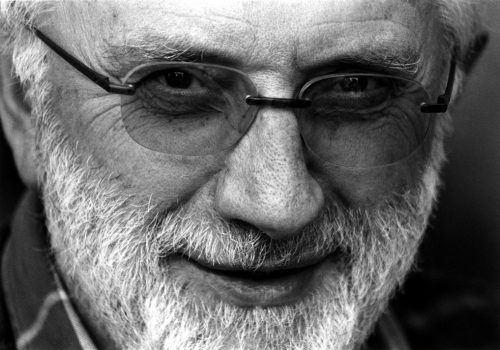

The Eye presents to you in the coming days extracts from these interviews, today LUCIEN CLERGUE.

The poet of the image (published interview includes 25 questions – here are 7)

Muriel Berthou Crestey. What was your first artistic emotion?

Lucien Clergue. Certainly, the violin, or more precisely, a concert given in Arles. I must have been 11 or 12 years old. One of the organizers, who was also a concert performer, was an ophthalmologist. He offered a free seat to my violin teacher for the purpose, he said, of his best student. I went. It was three Bach sonatas for cello. I was pierced. The next day I wanted to play Bach’s sonatas. Despite the reluctance of my teacher, we played them and it was the big event around which my life revolved.

B. C. Do you think that all moods are conducive to creation

C. There is a phrase by Igor Stravinsky that “inspiration is like children, you have to put it on the pot every morning”. I think you have to be wary of inspiration and work more like a baker makes his bread so that, at some point, it comes up. For a period, I took pictures every day, from morning to evening. Faced with such perseverance, he always ends up getting something out. There may be a little angel following you who, by seeing you work, directs you to a direction. So, we get into it. Of course, I live in a land of blessed bread where there is always light, even too much for some. Personally, I like the sun. Here in Paris, I peel cold when last Sunday, I was still doing photos on the beach, next to Arles. That has no price. It’s true that the soft light that the Americans love is so attractive; for example, Weston Atlantic Light is indescribable.

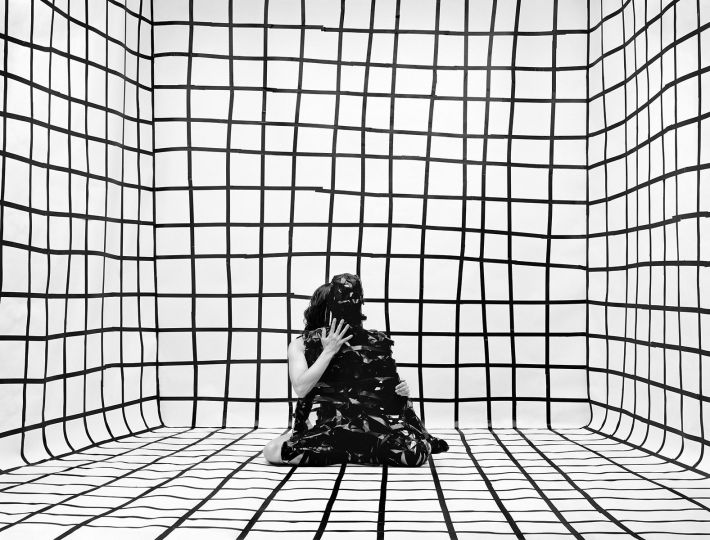

B. C. In zebra nudes, are games with light a way of dressing the body?

C. I had made several attempts of Nus zebra in Chicago but it was not very conclusive, until a friend living in New York offered to lend me his apartment for a while. Yellow blinds, magnificent, diffused a different light. The interstices between each blade formed particularly defined and thin welts. Often, I do not give my sources. The body is zebra but we do not know where these fine streaks come from. He seems to wear these welts himself. At other times, I make the report, when it interests me to show all the feminine curves as opposed to the rigidity of the venetian blind. But that also joins the music.

B. C. The use of framing confers anonymity on people. Is it a way to evoke a universal dimension, or to create a mystery of identity?

C. When I started the Nudes, censorship was violent; anonymity was first and foremost a way to protect my models. In addition, I wanted to give the image of the Woman and not Gilberte or Helen … The face, the hairstyle mark a time. In cutting my head, I gave an image of the eternal. Besides, I come from a city where there are a lot of ancient statues with their heads cut off, so I felt comfortable with that. It also allowed to give fullness to the breasts that are an obsession for me. I always wanted to know if I had been breastfed by my mother. Unfortunately, she was so sick that she had to confide in a nanny, mother of a bullfighter. I had the milk, but not the blood. So I never became a bullfighter. Compared to the framing, there is another aspect that fascinates me and that I use every time. When a woman poses, I always ask her to cross the right leg on the left, or vice versa, depending on my position. This is to create a taper that ends in whistle, avoiding the amputation of the left leg, since it disappears under the other leg. Then it’s always against the light.

B. C. In public reactions, would you like to find interpretations that match your original intention and your emotions at the time of shooting? Or do you prefer that viewers see different things?

C. Paul Eluard’s word “Give to see” is perfect for our adventure. What you have to consider is the book. Unlike the cinematograph that will create a montage by giving x seconds to such a shot, where you can not escape, a book allows the viewer to linger or not on each sequence. Born of the wave responds, for example, to a very precise construction and it is a case study that no one has ever highlighted. I am the only one to know him and to talk about it. In Western conception, a book is opened at the beginning and flipped through in order. In Eastern culture, on the contrary, we open the book by what we consider to be the end and we move in the other direction. From there, I wanted to make a universal book that could answer both speeches. This is my bestseller. I designed it mechanically with notebooks of 8 folded and a double page like the wave, which comes knocking at its own pace. I have often wanted to approach this dimension with people who are interested in books like Bernard Pivot, but no one has yet wanted to pay attention. The tenants of the verb are frightened by the image. It’s difficult to present photographs on television. Robert Delpire had a very good presentation at the Rencontres d’Arles, but he was a master of photographic editing.

B. C. The book is also a meeting place between literary and plastic creation. In Memorable Body, your images fit in with Paul Eluard’s poems. What was the genesis of this project?

C. I had made my first nudes and had shown them to Picasso who, jumping on the ceiling, gave me slaps saying: “It was you who did that …? Then, having shown them to Cocteau, Pierre Seghers discovered them just as he was working on the edition of Corps memorable. He balanced the illustrations of Valentine Hugo who were originally to accompany the texts to put my photographs in the place. It has adapted perfectly. It’s the absolute bestseller. This book dates from 1958. It is constantly reissued. The last is in 2003. It is extremely rare.

B. C. How was the adventure of the Rencontres d’Arles born?

C. Being a native of this region, I did this Photography Festival there, but if I had remained a violinist, it would certainly have been a Violin Festival. I think it happened at a crucial moment because the photography was totally abandoned. In the 1950s, there was no place for photography exhibition in Paris …

Muriel Berthou Crestey – Au coeur de la création photographique

ISBN 978-2-8258-0285-4

Editions Ides et Calendes