Photography books are as much works of public discourse, as they are personal albums. The more an image is considered, the more familiar it becomes until the line between Us and Them vanishes, and the image becomes a reference to our own life. As such, photograph books operate on several levels—inviting us to quietly contemplate life in the particular as a manifestation of universal experience. And so it goes that for this column I selected two books that resonate on this level in complementary ways.

Jasper, Texas: The Community Photographs of Alonzo Jordan by Alan Govenar (International Center of Photography/Steidl) is the history of a time and place before it became infamous as the site of one of the most brutal race crimes in recent history. On June 7, 1998, three white men in a pick-up truck dragged James Byrd Jr., a black man, to death.

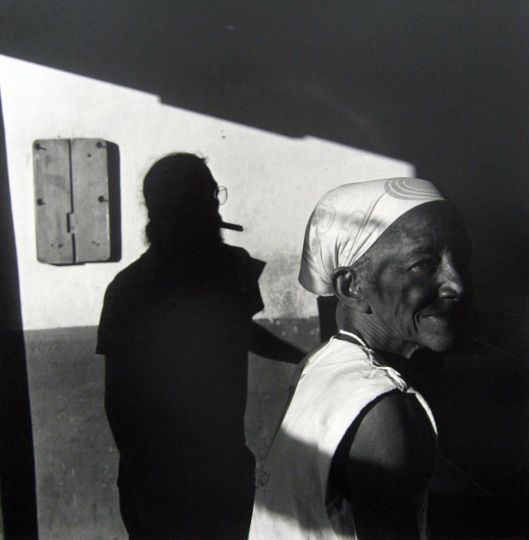

Mr. Byrd had been photographed in 1966 by Alonzo Jordan (1903–1984), a chronicler of the unseen African American populace of Jasper. A barber by trade, Jordan took up photography in 1943 to fill a need he recognized in the community. The result of his efforts is a powerful collection of pageants and parades, graduations and weddings—the small town social events that define lives, families, and generations. Jordan’s photographs show us what it was to be black and proud in Texas, one of the most virulently racists states in the Union, during the era that forever changed the relationship between the races in this country.

As Alan Govenar writes, “The history of race relations in Jasper is largely unwritten. Among African Americans, few are willing to talk publicly about bigotry and discrimination that existed in Jasper in the years prior to the Byrd killing. The federal mandates of the Civil Rights legislation ended legalized segregation, but integration in Jasper proceeded slowly. Today, many residents, white and black, still express feelings of resentment and apprehension. The James Byrd gravesite has been desecrated three times, and Rebel flags, readily purchased on the highway outside of town, still fly in yards scattered along the roadside, reminders of a troubled past and uncertain future.”

This barest of knowledge of what it must have been—and very well still may be—like to be black in Jasper makes Jordan’s photographs all the more remarkable. The dignity of human life, the integrity and respect to cultural traditions in the face of what we cannot fathom unless we have lived it, is powerfully presented in Jordan’s work. His gift is not about the formal construction of the photograph, but the way in which it is used. To document, to highlight, to draw attention to the people, the moment, the meaning of life as we know it—this is what Jordan accomplished during his time on earth—and the result is a book that is as much a collection of other people’s memories as it is a tribute to the American spirit. For the true spirit of America is not one that can be found in its history books—but in the behind-the-scenes stories that are told by those in the know. Jasper, Texas tells the stories that the media tries so hard to destroy—the stories of black pride, black family, black power in the face of the untold horrors of racism.

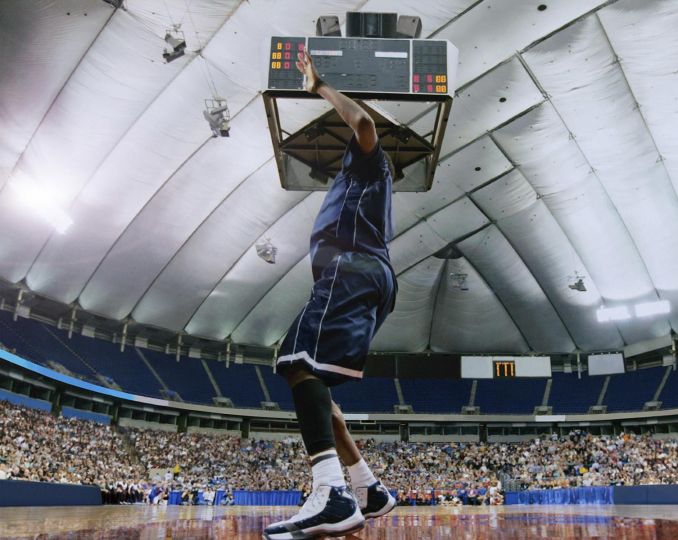

Fast forward to 1984 when Rick Rubin and Russell Simmons joined forced to create of Def Jam Recordings, the first major Hip Hop label. Against all expectations, it became a force to reckon with, redefining the image of black in America—and all around the globe. In tribute to the first quarter century of the label’s phenomenal success, Rizzoli has just released Def Jam Recordings, a twelve-by-twelve inch volume that is as much a chronicle of the music as it is to the photographs that defined a brand new aesthetic in popular culture.

Def Jam Recordings features work by Glen E. Friedman, Ricky Powell, Janette Beckman, Jonathan Mannion, David Corio, Danny Clinch, Johnny Nunez, Wayne Maser, Michael Lavine, and Ernie Panicioli, among many others, as it provides an oral history of the label’s historic rise to power. For anyone who has been a fan of Hip Hop since it became a force to be reckoned with, Def Jam Recordings is the ultimate photo album, a look back to a time in music that was truly cutting edge.

As Kelefa Sanneh writes in the book’s introduction, “This was the great idea behind Def Jam: not just that rappers could be transformed into mainstream stars, but that their single-mindedness and their idiosyncrasies—their obsessions with beats and rhymes, their disdain for signifiers of pop palatability, their loyalty to their old neighborhoods—were not incompatible with this transformation but, on the contrary, essential to it. Through hip-hop, a loudmouthed kid could go on from a neighborhood favorite to a Top 40 sensation—no crooning required.”

As so it was and has always been that Hip Hop is equal parts skills, bravado, and style—the last of these items best conveyed through the photographic form. The look of MCs and DJs (and then eventually of producers when the DJ was phased out) is central to defining this culture as it evolved, starting and sparking trends that have set the world on fire. Before videos were played on MTV, photography is what best conveyed the aesthetic of the art form; once videos became a mainstay, photographs became slicker than ever, lionizing these musicians as celebrity icons.

The beauty of Def Jam Recordings is that it is equal parts public and personal album. In many ways, popular culture has become a record of the collective conscious—the shared moments that so many of us have, no matter what race, gender, nationality, or age. Photography—like music—speaks all languages; we are fortunate that when considering any image that we can appreciate it on purely aesthetic merits, as well as on other levels. The photographs featured in Def Jam Recordings and Jasper, Texas share two sides of the African American experience. The local and the global stages are occupied by an experience that is inherently American, as seen through the lens of black history and culture. What makes each of these books so beautiful is that they show what makes humanity so powerful, speaking to all people about respect, pride, and love.

Sara Rosen

A selection of these works are currently on view at The Power Plant gallery in Toronto (Until March 4, 2012) (hyperlink to: http://www.thepowerplant.org. The exhibition includes Malabar People, a suite of 16 portraits of the denizens of a fictional 1950s nightclub.