…and still the chills come as the words reverberate in the ear, Martin Luther King Jr.’s voice as clear as the call of the clarion. “I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’

“I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

“I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heart of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but the content of their character.

“I have a dream today!”

King first spoke these unforgettable words on August 28, 1963, at the historic March on Washington, where he stood at the Lincoln Memorial before 250,000 people gathered at the National Mall in Washington, D.C., to mount a peaceful protest demanding Civil Rights, justice, and equality for African Americans nearly one hundred years after slavery was abolished in the United States.

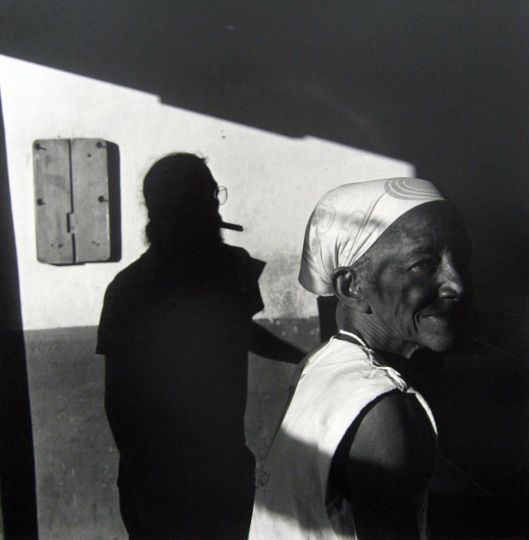

In tribute to the fiftieth anniversary of one of the proudest days in this country’s history, Getty Publications has just released This Is The Day: The March on Washington by Leonard Freed, with texts by Julian Bond, Michael Eric Dyson, and Paul Farber. Most of the seventy-five photographs featured here have never been published before, and taken as a whole they offer a compelling, powerful, and uplifting vision of the day itself—before, during, and after the march.

As Dyson writes, “The moral beauty of Freed’s photographs bathes the aesthetics that guides his flow of images. The folk here are neat, dignified, well-dressed—in a word, sharp, with all the surplus meaning the word summons, since black dress can never be divorced from political consequence…. Freed captures the simple dignity and the protocols of cool—the ethics of decorum—that characterizes large swaths of black life. And when his camera swings wide to include a vision of America too rarely noticed in the mainstream press at the time, and in some cases even now, he records almost mundanely, and hence rather heroically, the everydayness of the encounters between white and black. He allows the images to steep in the crucible for American race. One can almost catch the subliminal suggestion: This is what it should always be like.”

Indeed, the legacy of this historic day is that it offered to not only America but to the world a vision of the power that healing brings. We return again and again to the day, not only for what King verbalized for us but for what Freed’s images say. We see in these images the American ideal: all power to the people, and for that we reflect with a quiet reverence and hopeful spirit that the dream shall be fulfilled.

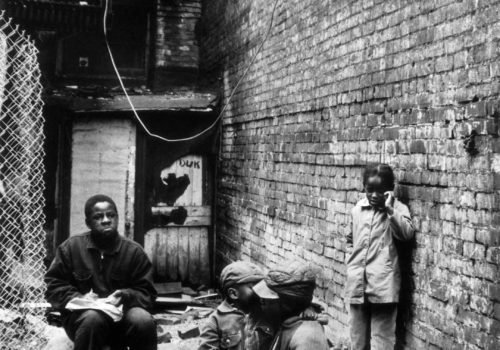

Fast forward four years and hundreds of miles north to A Harlem Family 1967 by Gordon Parks (Steidl/The Gordon Parks Foundation/The Studio Museum in Harlem). In the fall of 1967, Parks spent a month photographing the everyday lives of the Fontelles, and first published the work in a special March 1968 issue of LIFE focusing on race and poverty in American cities. The book, commemorating the November 2012 centennial of Park’s birth, features the original series along with dozens of never-before published work to the cumulative effect that reminds us of what Martin Luther King, Jr. was fighting to honor and protect.

As Parks wrote in the LIFE piece, “What I want. What I am. What you force me to be is what you are. For I am you, staring back from a mirror of poverty and despair, of revolt and freedom. Look at me and know that to destroy me is to destroy yourself. You are weary of the long hot summers. I am tired of the long hungered winters. We are not so far apart as it might seem. There is something about both of us that goes deeper than blood or black and white. It is our common search for a better life, a better world. I march now over the same ground you once marched. I fight for the same things you still fight for. My children’s needs are the same as your children’s. I too am America. America is me.”

Parks, like Freed, has a deep feeling for humanity, not just for the condition of black folk in America but for the spirit itself, for the deep essence that lives in each one of us, the sacred made flesh. His photographs show us not only how poverty looks but how it feels—the pain, the fear, the isolation, the alienation, the very being of the condition itself. In these photographs we understand even if we cannot fully articulate, even if we’ve never lived this life, Parks brings the intimacy of love and of agony to a place where we cannot look away. We cannot pretend. Things have not gotten better; the Fontelles are still very much a part of the American fabric.

In the Editor’s note, Parks explains why he created this work, “I got fed up with hearing all these people, even Negroes asking, ‘Why are those people rioting?’ My personal project was to show them why. You have to know what they go through before you can understand why all this violence takes place—and it is going on each week in ghettos across the country. My whole purpose was to bring to the people of the United States an inner look at the thing that brings chaos in the summer. I wanted to show what it was like, the real, vivid horror of it—and the dignity of the people who manage, somehow, to live with it.”

It is this dignity that Parks and Freed share with their subjects, with the greater narratives themselves, with the tales of America that are sometimes told, but more often than not ignored or vilified through racial propaganda. It is this dignity that speaks to us fifty years later, generations apart, with the full knowledge that the more things change, the more they stay the same—but the future has yet to be told.

Miss Rosen