“Although I’d worked with Guy [Bourdin] for a few intense years, rarely do I feel I truly knew him. He remained enigmatic and complex, and I was a young girl captured by his lens, lucky to have been present during a high note of his career and thankful to have been a part of it,” writes Nicolle Meyer in the afterword to Guy Bourdin: A Message For You (SteidlDangin), which Meyer curated to exquisite effect.

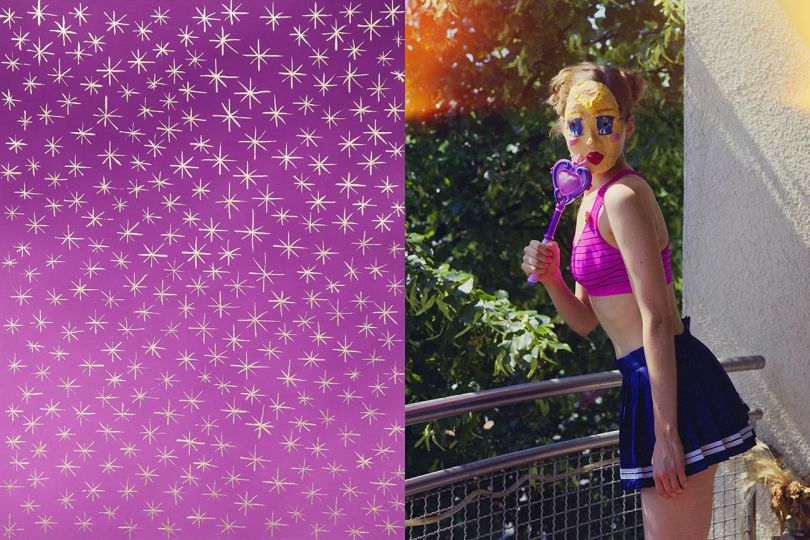

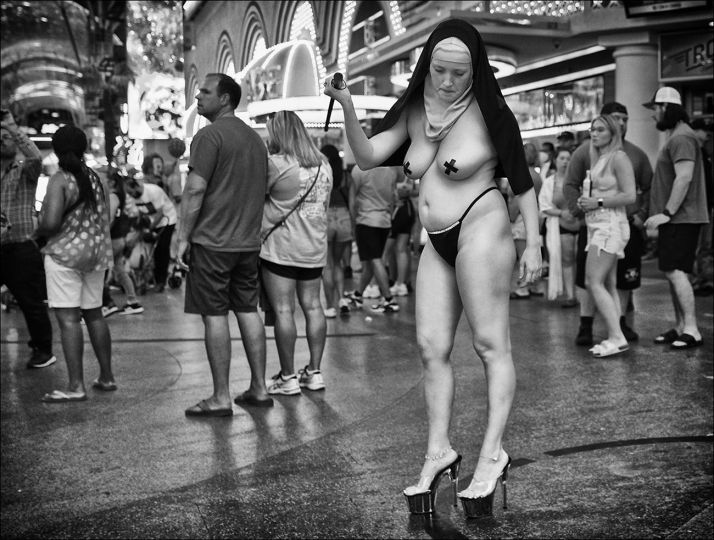

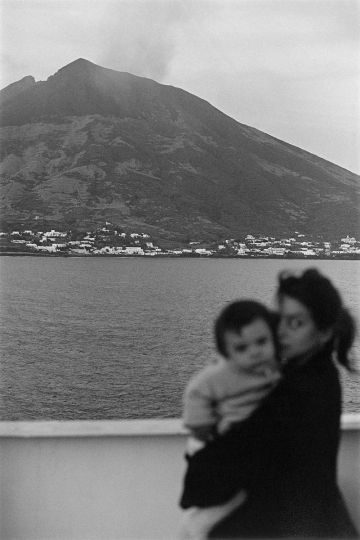

Here we witness the dialogue between artist and model, a conversation that reads like we are overhearing whispers in a darkened room. In Bourdin’s work, there is a tension between intimacy and exposure, vulnerability and strength, a sense of timeless placelessness that makes every photograph its own construction of reality that combines the sacred and the profane. We are no longer looking at a mere fashion photograph but standing before the portal into another realm itself. The images have an edgy romanticism that is alluringly disturbing. There is a sense of theater, of drama, of an intensity that transcends the idea of the fashion photograph and pushes into a fantastical neverland that insistently reminds us of the dark undertow of sex.

As Meyer recalls, “The scenes Guy created were very romantic, though always stamped with his unique interpretation of the world. He had decadently plump fresh roses attached to the branches of an apple tree beneath which we posed in dappled sunlight—Audrey, graceful in pink, alighted on a sofa dragged out into the field from the chateau and I, in a royal-blue taffeta dress, grasped the branches above…. Mise-en-scenes developed—borders breached between dream and reality. It was fantasyland. Pachelbel cascaded from a little portable record player, through the chateau and out into the garden. The images Guy crafted could have been stills from a period piece—a mélange of Marquis de Sade and Barry Lyndon.”

It is the spirit of creation, of creativity, of the powerful sublime that builds a tension at once beautiful yet hinting at a danger that lurks beneath the surface of things. It is this darkness set amidst the beauty of the image, the model, and the clothes that makes a Bourdin photograph hauntingly memorable. We feel the surreal with every turn of the page, its spirit lingering as our eyes take in the rich and luxuriously crafted sense of the strange. There is a feeling of being at once close and far away, a consistent estrangement that makes each of these images enigmatic in their ability to defy the immediacy of the photograph itself.

Meyer observes, “Now looking at Guy’s work, I see a man far ahead of his time, using the ephemeral fashion magazine as his medium, as his way to reach a larger public—a spectrum that at that time the art world would not have provided him, and certainly not with the same immediacy. He could enter into lives from the secure venue of a glossy magazine, provoke a reaction, and do so on regular basis—confronting the reader with hauntingly beautiful fantasies and introducing an edge never before seen in fashion magazines. Guy, in his own unique and uncompromising manner, blurred the line between art and commercial photography, undoubtedly using the glossy page to reflect an idea in which the clothes and and accessories became secondary—mere components of the photo. Granted, sometimes very important components, but nonetheless, never the focus. Narrative paralleled the composition.”

And it is here that Bourdin’s genius takes hold. Subversion is a theme throughout his work: subversion of the subject, the medium, the genre, and the form of representation, but of the viewer as well. To consume a Bourdin image set amidst more mundane fare is to quietly do the work of a revolutionary by infiltrating the system from inside itself. Bourdin’s genius was his ability to make the act of representation an act unto itself. The mystery of his images reflects the complexities of his mind and it is with great pleasure that we may consider Bourdin’s collaboration with Meyer on its own terms.

Miss Rosen