Janette Beckman spent the summer of 1983 in Los Angeles, staying in the home of a good friend who was then managing the pop group, The Go-Gos. While in town, she came across a newspaper piece on the East L.A. gang scene; the story had no photographs, so Beckman took to the streets to see for herself. Although she was warned against visiting the area by local acquaintances, Beckman was young, brash, and bold and armed herself with just a Hasselblad and a box of prints to share her work.

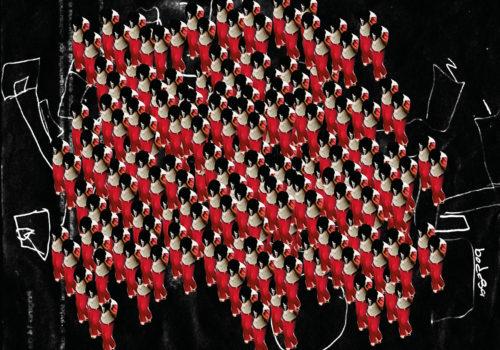

Beckman drove her rent-a-wreck car to East LA, and began hanging out at El Hoyo Maravilla, a park in the neighborhood, which is also the name of Beckman’s newest artist book, a limited edition of 500 published by Dashwood Books. The photographs were culled from the collection of negatives that sat in her closet for over twenty-five years; she showed the photographs when they were first taken but no one expressed interest in it at that time. Today, it is a different story, as the photographs have taken on a new life, having been published online and spurring contact from the subjects after all these years.

Beckman’s portraits are of a time and place that is at once foreign and familiar, people strongly tied to the culture and the community from which it sprung. For Beckman, who was a rock & roll photographer working for Melody Maker, a weekly music magazine, and shooting album covers at the time, this foray into a new culture had the hallmarks of a world that was just as misunderstood as the world she had left behind.

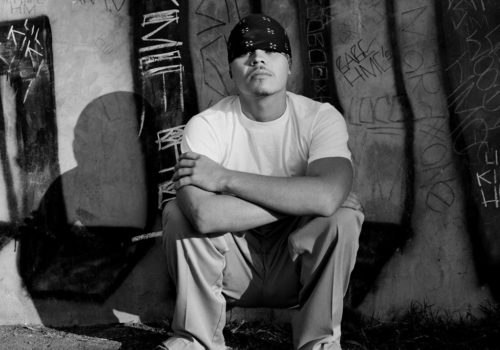

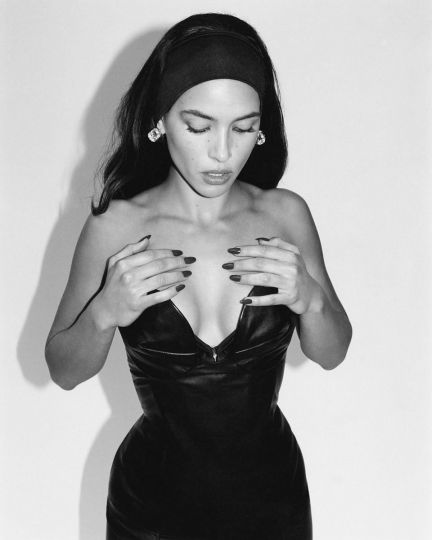

Like the punks, skinheads, mods, and rockers that Beckman shot during the late 70s and early 80s in London, the gang members she met in Los Angeles were a people of a time and place, who made themselves part of the group by conforming to social codes that dictated behavior and appearances. It was these appearances that first drew Beckman in, with their definitive style that included perfectly pressed jeans and pants with a top crease, bandanas and shaved eyebrows, and white t-shirts and tank tops worn without anything else. The women wear strong make-up, dark eyeliner and hard lips, with long tresses of flowing hair while the men are also perfectly groomed. The gang codes of Los Angeles included hang gestures, graffiti, and tattoos, all signifying an allegiance to the group that protects and defends their neighborhood.

As Beckman came to discover, the deeper story is one of family, of a group of people that were native to California before, during, and after the Spanish and American occupation and acquisition of the land over the past three hundred years. As Beckman connected with her subjects, she was invited into their homes, meeting mothers and grandmothers and relatives, hanging out with older brothers, learning about the structure of gangs and the way in which they played a role in the community. “It was like meeting a big family They were all delightful,” Beckman observes, before noting how one kid wanted to show her his machine gun, though she doesn’t have a photographs of the encounter itself.

This is because Beckman’s photographs are not about the negative side of gang life. They are not an expose on violence, politics, or the economics of an historically oppressed people living in America. Instead, Beckman focuses on the love that exists in the community and the self-love that comes from pride. The only photograph that displays a weapon is the one of a couple standing in front of their home, where she is playfully holding the knife to his neck as he smiles comfortably, a bottle of Pepsi in his hand. It’s the “American Gothic” of 1983, Chicano style, reminding us once again that America is a land of opportunity, passion, and love for the world that we together build.

Miss Rosen