Our collaborator CYJO sends us this tribute to the late Japanese photographer Miki Ono with this interview of his son Shin Ono.

Miki Ono’s work was first introduced to me in 2023 when my dear friends Shin and Shizuka visited Miami. Shin’s father, Miki, was 92 at the time and in a care home in Japan. Shin is a photographer who I consider one of the best professional retouchers in the industry, having worked for Pier 59 Studios and many well known photographers since the 1990s.

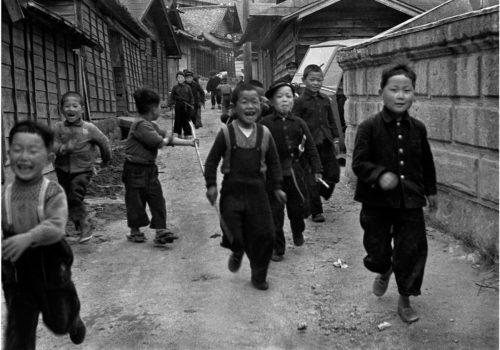

During the visit, Shin shared his father’s remarkable portraits of people, mostly children, in the Tohoku region where he grew up. These images, taken using extra film he had from magazine assignments, captured children playing and laughing with the same exuberance found in Helen Levitt’s Bronx street photography. The vitality seen in the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson and Garry Winogrand also came to mind. Experiencing these images and learning about Miki’s legacy, along with Shin’s own journey in photography made it clear this was a story worth sharing, a story of a father, a son, and their shared passion for photography.

Below is my edited conversation with Shin Ono.

C: Can you tell me about your father?

S: My father, Miki Ono, passed away on June 1, 2024—coincidentally Japanese Photography Day. He worked as the photographer for Tohoku Electric Power’s public relations magazine Home and Electricity (later renamed White Country Poem) for nearly 40 years since 1955. He captured the landscapes of the seven prefectures of Tohoku and the lives of the people who lived there since 1948 when he formed a photography club at his high school. My father started his career by submitting and winning numerous photo awards by national photo magazines. He constantly showed his work through exhibitions and publications in Japan, which included those kid’s images I showed you.

Without any pretense, my father’s work had a Zen-like quality. It reflected his presence as an equal among all forms of life and his sense of being guided to a certain place and time. Even now, there is something undeniably compelling in his photographs that continues to draw people in.

C: What kind of stories did he cover in the magazine?

S: The magazine covered culture related stories relevant to the Tohoku region where the electric power company provided their services. I believe he was the only photographer for the magazine for many years, providing images of landscapes, landmarks, temples, local festivals, Buddha statues, and rock carvings, many which had haiku carved into them. If he had left over film from his jobs, he took additional images.

C: I love how many of the images are culturally saturated with such detail, from the people to their context. It’s highly informational showing the raw and the real.

S: He wasn’t concerned with editing out unwanted power poles or people to create postcard-like compositions or “picture-perfect” images. Rather, he illuminated the poetry of everyday life and the people who lived it, using light as one of his mediums. Some photographers tell stories about waiting for days in pursuit of perfect natural conditions to capture the right mountain shot, but my father didn’t work in that way. In an essay accompanying one of this photographs, he wrote, “By chance, I turned the wheel and drove down a path. Just as I arrived, the light broke through perfectly, and I was able to take a wonderful picture.” It seems to me that his life was about attracting those moments of serendipity. What truly mattered was this ability to be drawn to those encounters, to be fully present.

Talking about this makes me think about the time I was in college. Knowing I couldn’t possibly compete with my father in photography, I resolved to become a trendy contemporary artist instead. So, I studied art in college where students were encouraged to be experimental and to think outside of the traditional norms of image making. When I showed my father a graphical series I worked on, which used techniques like multiple exposures and slides, he silently gazed at it for a while and then said only one sentence: “Something is missing.”

C: What did he mean by that?

S: I will never know exactly what he meant. My taciturn father never explained. Perhaps my father was trying to tell me that straightforward photography—unadorned and true— was a far more meaningful form of art.

C: When looking at these portraits of children and sometimes during rough times after the war, these feelings of hope, laughter, and what’s to come dominate. They exude so much vitality.

S: In his youth, he experienced three major catastrophes. In 1945, he watched the city he grew up in, Sendai, burn to ashes after it was bombed during the war. When he evacuated to Ichinoseki in the Iwate Prefecture, it suffered major flooding in 1947 and again in 1948, submerging the entire ground floor and costing him his violin.

C: His violin?

S: Yes. He was thinking of becoming a musician. But losing his violin became a turning point which shifted his passion from music to photography. He remained positive through it all and even found joy in those challenging situations.

C: You mentioned earlier that your father wasn’t a documentary photographer. I couldn’t quite understand this.

S: Photography in Japanese, sha-shin, means sha (to capture) and shin (the truth). But he had a loose and sarcastic way of identifying himself and called himself sha-uso-ka, sha (to capture), uso (false or lie), and ka (specialist). He believed each person had a different truth in the vast ocean of truth where truth was impossible to really capture.

Another criteria that documentary photography has, at least within the Japanese context, is to go somewhere and to broadcast an idea of a truth that’s happening somewhere else. And he didn’t do this. He captured what he encountered at the moment and right in front of him.

C: So, it wasn’t about shaping a narrative for him. It was about sharing the moments he experienced and presenting them as is. I strongly believe in this. Our understanding of what we know is so much shaped by our limited experiences and within our cultural context. And this knowledge can shift or evolve over time.

S: I learned more about my father after his death, after cleaning up his things and speaking to people who were connected to him. For example, I thought his published work was known by many in the region who received electricity from the company but learned that the magazine was distributed among select customers and staff. My father’s work was recognized within the photography community in Japan and not so much by the general public. But this may change as Sendai Mediatheque Library is hoping to secure support to scan and archive his thousands of negatives for the public as an educational resource. They think his records of Sendai would memorialize the history of the city.

C: That’s wonderful! You mentioned your father being taciturn, and I immediately think of the many households of Asian and Asian American friends of mine with fathers who didn’t talk much. The love was there, but it was difficult for some fathers to emotionally speak with their children on a deeper level due to cultural influences at the time. Was this the same in your case?

S: Not at all. My father didn’t talk much, but he was actually a strong presence in my upbringing. When he wasn’t on assignments, he was in the household with my brother and me. My mother was also home because she worked in our living room, helping Miki’s father’s cottage industry. However, she worked long hours, sometimes overnight, hand painting faces, outfits and Japanese poems on kokeshi dolls. So, my father played with my brother and I when we were kids. And we did a lot of photography together. He would take me on his location trips as a child, and I learned how to take pictures and develop images in his darkroom. In fact, I won a Nikon FM camera from a competition that my father encouraged me to participate in. And from then on, I used my own camera with my father’s 20mm lens, which I ended up using for a long time. Even now, I use a 75mm for my 4×5 camera, which is close to how a 20mm lens reads on a 35mm camera.

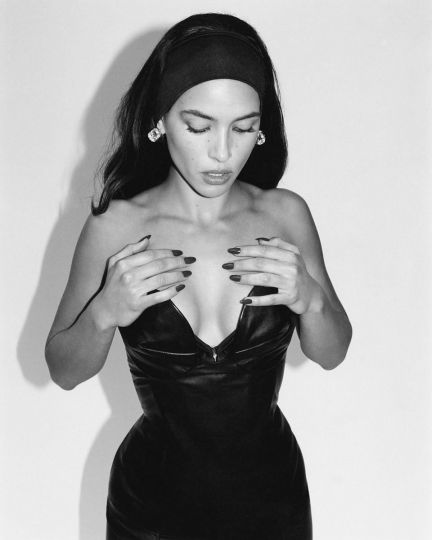

C: It’s great to see you active, taking portraits of your friends. And congratulations with your book which is available in Japan. It appears that your work emphasizes fundamental concepts and takes a direct, straightforward approach.

S: I have been using my old wooden 4×5 camera to shoot portraits of people in black and white for years. Most of them are simply composed with the subjects standing still in front of me, and I try to stay away from anything out of the ordinary.

My father’s words—“There’s something missing”—still weighs heavy in my mind no matter what I do. He never provided a list of dos and don’ts or told me whether I was getting closer to what was missing, but I hope I’m getting closer to it now.

About Shin Ono

Born in 1965 in Sendai, Japan, Shin is a photographer inspired by his father, Miki Ono. He studied modern art at Tsukuba University and began showcasing street photography in the early 1990s. Since moving to New York in 1998, he continues to photograph people and landscapes using his wooden 4×5 film camera. Shin’s portrait book FACE TO FACE is available on Amazon.co.jp.

www.shinono.com @shin_ono

About the writer

CYJO is a Korean American artist based in Miami whose work, since 2004, focuses on identity of person and place, exploring culture and categorizations. She is also co-founder of thecreativedestruction, an art collaborative with Timothy Archambault, and a long-time contributor to L’Oeil de la Photographie.

www.cyjostudio.com @cyjostudio